S hep apologized to my friendand quickly.

I didnt mean to snap, son. He sighed and drew a palm over his mouth. Its just that I love the radio shows. But the books! I slave over the books! They have to be exactly right. Exactly! Right! Why he was opening up to a tenth-grader Ill never know (nor will my fellow tenth-graderit happened to him, not me). But open he did.

I know if Ill be remembered, Ill be remembered for the radio shows, not the books [the movie was still in the future]. I guess thats okay. But, see, the radio shows only have to make sense. The books are Jean Shepherd paused, and if he was doing so for emphasis it worked. My friend remembered the pause as he retold the story a decade later: The books are forever!

And they are.

When you read, when you laugh, when the seminal truths of the universe that come out of the sky and reveal themselves to the observant of the Midwest of 1937 or the Northeast of 2013 or the West of 2274 again peek through and make you shiver with their transcendent honesty and applicability, just remember Jean Shepherd sweated his privates off to tell you these timeless facts, and to get the message exactly rightbefore the muse escaped his vision. Shep would have found these spirited transcriptions of his army stories also got it exactly right!

So shout Excelsior! at the nearest Fathead, and thank whatever deity you favor that this flawed man who couldnt resist yelling at one of his fifteen-year-old radio fans, existed for a timeJust to tell thee

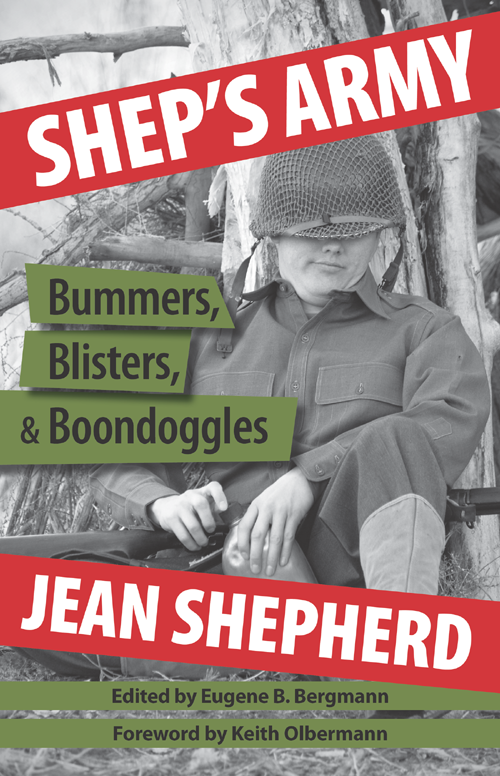

I nducted into the army at age twenty, Shepherd served from July 1942 until December 1944, spending his entire time in the States. Thus, he has no tales of battlefield valor to tell, but he does tell some doozies about KP with four hundred dead chickens, USO hospitality with a Daisy Mae look-alike, and near death on a desolate field of telephone polesand with that, you still aint heard nothin yet about his adventures on the home front.

Because he is so secretive about details of the real life he lived, the truth of what he did and where he did it is hard to come by. He sometimes speaks of being at Camp Crowder, Missouri, where indeed there was a large Signal Corps training facility. In more than one of his tales, he speaks of going into the nearby town of Neosho, Missouri, where, just as he fictionally alludes to it, families had the custom of inviting soldiers home for Sunday dinner. He appears to have spent much of his time in a semitropical environment near or in the Everglades. He frequently talks about the intense heat, the insects, and the tropical flora and fauna. This was the historical reality of Camp Murphy, a radar training base within an enlisted mans short bus ride to West Palm Beach, Florida, and the likely suspect.

Army inductees who were ham radio operators as was Shepherd were often automatically marshaled into the Signal Corps, the army unit responsible for communication. We know he was a capable Morse code operator from early adolescence, and through his army stories, he claims to have learned everything from climbing telephone poles to operating the new-fangled radar equipment. He sometimes claims to have been in a mess-kit repair company, whose insignia was mess kits with crossed forks on a background of SOS. (Anyone needing a definition of SOS should ask a soldier about creamed chipped beef on toast.)

Even though most of his tales are anchored in the Signal Corps, all are universal regarding what he sees as the military world. They depict what he saw of the lives of millions of GIs living a day-to-day reality of constraint, discomfort, and sometimes the wearing away of the polite veneer of civilized behavior. Millions of ordinary guys who never see the dramathe hellof war up close, and therefore seldom have the opportunity to perform either bravely or cowardly, or even to carry on in the face of calamity, simply live, struggle, and survive the dehumanizing indignities of military life in a way that, for Shepherd, is seldom shown and always unsung. He believes that such experience has interest and value, especially because it is the reality for most of us most of the time. And he knows how to depict it with understanding and frequently with laugh-out-loud humor.

Surveying the audios of his available radio broadcasts gives added appreciation for his many armed services stories. They are very popular with both listeners and readers, but other than a few published decades ago they have not, until now, become available in print. We have only about fifteen hundred of the approximately five thousand broadcasts that have so far surfaced from which to select army stories to publish. One wonders what gems of broadcasts, and the gems of stories within them, have simply disappeared into the ether. Yet many glories survive. Exploring the available tapes, one finds tales that fit every part of his army career, suggesting a rough sequence.

First, induction, or encounters with an alien way of life; then learning technical skills and enduring the rigorous training, both of which mature him; then a focus on the skills the army chooses to use, practiced in the semitropical jungles and swamps of Florida. Throw in some attention to the general life-in-the-military experiences such as payday, passes, train rides and, finally, the not entirely smooth transition back to civilian life.

Shepherd tells his army stories, indeed all his stories, in no special orderrandomly it seemseach self-contained. Once one begins to cull them and organize them, however, they suggest a coming-of-age-in-the-army narrative that can reasonably be deemed Jean Shepherds Army Life Novel.

THE REAL, AND UNREAL, SHEP

For many people, influenced by his intimate, first-person radio style, Shepherds stories, spoken and written, appear intensely autobiographical, butbrace yourselvesthey aint. Even when he is consciously trying to remember his life, Shepherd has a hard time keeping a straight face. He has a penchant for mischievous deception, even outright obfuscation and self-contradiction, when describing the facts of his life to reporters. For those who know his works, his comments the year before he died tell it like it probably was: I want my stuff to sound real. And so when I tell a story, I tell it in the first person, so it sounds like (by the way, thats the best way to tell a story, in the first person), that it sounds like it actually happened to me. Well, it didnt.