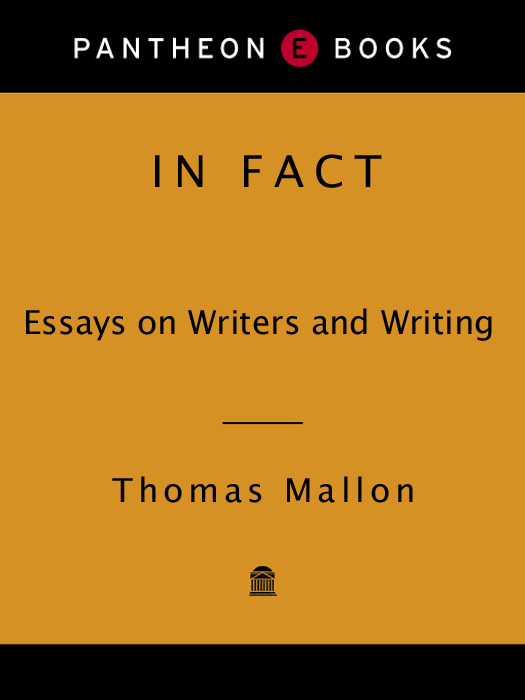

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: Copper Canyon Press: Excerpt from Fair/Boy Christian Takes a Break from The Shape of the Journey: New and Collected Poems by Jim Harrison. Copyright 1998 by Jim Harrison. Reprinted by permission of Copper Canyon Press, PO Box 271, Port Townsend, WA 98368-0271. Harcourt, Inc.: My Quarrel with the Infinite from Hotel Insomnia by Charles Simic. Copyright 1992 by Charles Simic. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Inc. Louis Simpson: The Hour of Feeling from Searching for the Ox by Louis Simpson. Copyright 1976 by Louis Simpson. Reprinted by permission of Louis Simpson.

is an extension of this copyright page.

PS 379. M 287 2001 813.509dc 21 00-056503

Contents

Up from Academe:

An Introduction

I T SAYS SOMETHING about the specialized repetitions of academic life that a journal called Joseph Conrad Today can be continuously published. And it says something about my days as an assistant professor that, twenty years ago, I was writing for it. Twentieth-century British literature was my field, and like most of my colleagues in pursuit of tenure at Vassar, I was accumulating publications in periodicals read chiefly by the other people writing in the same issue.

William W. Bonneys Thorns and Arabesques: Contexts for Conrads Fiction was the Johns Hopkins University Press book I had to review for Volume VI, nos. 34 of JCT. The following sentence is typical of the books language, an idiom spoken by the academic species one level above minethat is, associate professors in pursuit of promotion: In these instances, a seemingly meaningful logical surface is subverted by the ontic vacancy of raw diversity established through a plurality of multiplicative inverses, to which the very idea of orderly and sequential monogenesis is indeed alien.

Alien, indeed. If Mr. Bonney will forgive me, I wrote after closing his quotation, I will make my point in a mere eight syllables: no one should write like this, ever. The reviews last sentences read, at this remove, like an urgent note to myself: I fear we have entered a kind of commentators My Lai. We have reached the point where we are destroying language in order to explain it squeezing out the last humble Anglo-Saxon syllable from a critical prose that is rapidly moving beyond the Latinate and towards the Martian. I was telling myself to look for another job.

In a roundabout way thats what I began to do, by reviewing for regular newspapers and National Reviewa magazine viewed by my colleagues as not only politically suspect but positively flashyand by publishing a study of diaries (A Book of Ones Own, 1984) that was a sort of belletristic curiosity. By the time I sat on the English departments hiring committee in the fall of 1987, the madly theoretical work of professors like Bonneywho scorned critical factors like biography as extralinguistic presenceshad already given way to a preoccupation with nothing but the social and historical circumstances of literature. Issues of race, class and genderinvoked so often and with such automatic simultaneity that they seemed to be one angry word, raceclassgenderwere fast becoming the only avenues of inquiry into literary texts. (Talk of books disappeared with the ditto machine and card catalog.) And yet the language employed in these new political pursuits, evident in the dissertation chapters presented by applicants to the hiring committee, was just as pretentiously ugly as the lingo that had made the theorists, such a short time ago, feel so smart.

By 88 I was publishing fiction along with literary journalism, and I wanted out. I gave up tenure and taught part-time for a few years, during which, I must add, I was always treated well, even fondly, like some back number spared the bindery and allowed to keep its torn cover. Just before I left Vassar for good, several months before my fortieth birthday in 1991, I gave a whole course on Mary McCarthy, the colleges most famous alumna and the subject, years before, of my own undergraduate honors thesis at Brown. Mary (eventually a friend) has been without question the most enduring influence on my life as a writer. In fact, it was probably a volume of her essays, On the Contrary (1961), that made me want to become one at all.

Marys glamour and reputation for sexual daring (Vassar took years to get over The Group) left some who read her criticism surprised by its essentially conservative nature. Her imagination was premodernist, and despite that twentieth-century academic specialty, so mine has always been. In all the years I was teaching Joyce and Woolf, my heart and mind were actually closer to Trollope and Thackeray. McCarthys essay The Fact in Fictionshe was all for itspoke forcefully to me when I read it thirty years ago, and Im not surprised that my own fiction eventually settled into the precinct of the historical novel. Like Mary, I began publishing fiction only after Id written a good deal of criticism and argument, and for better and worse the developmental sequence is evident: in my novels, narrative comes less easily than the construction of a characters background or commentary on his motives. Reluctant to let go of the essayists prerogatives, I have never written a novel outside the third person. Even amongst the diarists in A Book of Ones Own, practitioners of the ultimate first-person form, I always leaned toward the panoramic chroniclers, the ones who looked outward upon their times more than inward upon their lives. Theres an element of Mary here, too: she once declared a resolute preference for sense over sensibility, and in my own essay Enough About Me, grouped in the Biographical section of this book, I find myself writing this about a clutch of modern memoirs very different from McCarthys Memories of a Catholic Girlhood: I would rather end the day having had one clear thought than one strong feeling.