YOU PEOPLE COME into the marketthe Greenmarket, in the open air under the downpouring sunand you slit the tomatoes with your fingernails. With your thumbs, you excavate the cheese. You choose your stringbeans one at a time. You pulp the nectarines and rape the sweet corn. You are something wonderful, you arepeople of the cityand we, who are almost without exception strangers here, are as absorbed with you as you seem to be with the numbers on our hanging scales.

Does every sink grow on your farm?

Yes, maam.

Its marvellous. Absolutely every sink?

Some things we get from neighbors up the road.

You dont have no avocados, do you?

Avocados dont grow in New York State.

Butter beans?

Theyre a Southern crop.

Who baked this bread?

My mother. A dollar twenty-five for the cinnamon. Ninety-five cents for the rye.

I cant eat rye bread anymore. I like it very much, but it gives me a headache.

Short, born abroad, and with dark hair and quick eyes, the woman who likes rye bread comes regularly to the Brooklyn Greenmarket, at Flatbush and Atlantic. I have seen her as well at the Fifty-ninth Street Greenmarket, in Manhattan. There is abundant evidence that she likes to eat. She must have endured some spectacular hangovers from all that rye.

Farm goods are sold off trucks, vans, and pickups that come into town in the dark of the morning. The site shifts with the day of the week: Tuesdays, black Harlem; Wednesdays, Brooklyn; Fridays, Amsterdam at 102nd. There are two on Saturdaysthe one at Fifty-ninth Street and Second Avenue, the other in Union Square. Certain farms are represented everywhere, others at just one or two of the markets, which have been primed by foundation funds and developed under the eye of the city. If they are something good for the urban milieutumbling horns of fresh plenty at the peoples feetthey are an even better deal for the farmers, whose disappearance from the metropolitan borders may be slowed a bit by the many thousands of city people who flow through streets and vacant lots and crowd up six deep at the trucks to admire the peppers, fight over the corn, and gratefully fill our money aprons with fresh green city lettuce.

How much are the tomatoes?

Three pounds for a dollar.

Peaches?

Three pounds for a dollar twenty-five.

Are they freestones?

No charge for the pits.

How much are the tomatoes?

Three pounds for a dollar. It says so there on the sign.

Venver the eggs laid?

Yesterday.

Kon you eat dum raw?

We look up from the cartons, the cashbox, the scales, to see who will eat the eggs raw. She is a good-looking big-framed young blonde.

You bet. You can eat them raw.

How much are the apples?

Three pounds for a dollar.

Three pounds, as we weigh them out, are anywhere from forty-eight to fifty-two ounces. Rich Hodgson says not to charge for an extra quarter pound. He is from Hodgson Farms, of Newburgh, New York, and I (who come from western New Jersey) have been working for him off and on for three months, summer and fall. I thought at first that I would last only a week, but there is a mesmerism in the selling, in the coins and the bills, the all-day touching of hands. I am often in charge of the peppers, and, like everyone else behind the tables by our truck, I can look at a plastic sack of them now and tell its weight.

How much these weigh? Have I got three pounds?

Thats maybe two and a quarter pounds youve got there.

Weigh them, please.

There it is. Two and a quarter pounds.

Very good.

Fantastic! Fantastic! You see that? You see that? He knew exactly how much it weighed.

I scuff a boot, take a break for a shiver in the bones. There are unsuspected heights in this game, moments that go right off the scale.

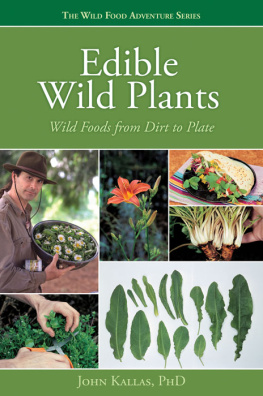

This is the Brooklyn market, in appearance the most cornucopian of all. The trucks are drawn up in a close but ample square and spill into its center the colors of the country. Greengage plums. Ruby Red onions. Yellow crookneck squash. Sweet white Spanish onions. Starking Delicious plums.

Fall pippins (Green as grass and curl your teeth). McIntoshes, Cortlands, Paulareds. (Paulareds are new and are lovely apples. Ill bet theyll be in the stores in the next few years.)

Pinkish-yellow Gravensteins. Gold Star cantaloupes. Patty Pan squash.

Burpless cucumbers.

Cranberry beans.

Silver Queen corn. Sweet Sue bicolor corn, with its concise tight kernels, its well-filled tips and butts. Boston salad lettuce. Parris Island romaine lettuce. Ithaca iceberg crunchy pale lettuce. Orange tomatoes.

Cherry Bell tomatoes.

Moreton Hybrid, Jet Star, Setmore, Supersonic, Roma, Saladette tomatoes.

Campbell 38s.

Campbell 1327s.

Big Boy, Big Girl, Redpak, Ramapo, Rutgers London-broil thick-slice tomatoes.

Clean-shouldered, supple-globed Fantastic tomatoes. Celery (Imperial 44).

Hot Portugal peppers. Four-lobed Lady Bell glossy green peppers. Aconcagua frying peppers.

Parsley, carrots, collard greens.

Stuttgarter onions, mustard greens.

Dandelions.

The people, in their throngs, are the most varied we seeorthat anyone is likely to see in one place west of Suez. This intersection is the hub if not the heart of Brooklyn, where numerous streets converge, and where Fourth Avenue comes plowing into the Flatbush-Atlantic plane. It is also a nexus of the race. Weigh these, please. Will you please weigh these? Greeks. Italians. Russians. Finns. Haitians. Puerto Ricans. Nubians. Muslim women in veils of shocking pink. Sunnis in total black. Women in hiking shorts, with babies in their backpacks. Young Connecticut-looking pants-suit women. Their hair hangs long and as soft as cornsilk. There are country Jamaicans, in loose dresses, bandannas tight around their heads. Fifty cents? Yes, dahling. Come on a sweetheart, mon. There are Jews by the minyan, Jews of all persuasions white-bearded, black-bearded, split-bearded Jews. Down off Park Slope and Cobble Hill come the neo-bohemians, out of the money and into the arts. Will you weigh this tomato, please? And meantime let us discuss theatre, books, environmental impacts. Maybe half the crowd are menmen in cool Haspel cords and regimental ties, men in lipstick, men with blue eyelids. Corporate-echelon pinstripe men. Their silvered hair is perfect in coif; it appears to have been audited. Easy-going old neighborhood men with their shirts hanging open in the summer heat are walking galleries of abdominal and thoracic scarsBrooklyn Jewish Hospitals bastings and tackings. (They do good work there.) A huge clock is on a tower high above us, and as dusk comes down in the autumn months the hands glow Chinese red. The stations of the hours light up like stars. The clock is on the Williamsburgh Savings Bank building, a skyscraper full of dentists. They go down at five into the Long Island Rail Road, under us. Below us, too, are all the subways of the city, in ganglion assembled.