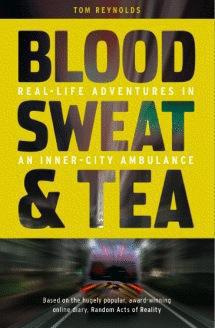

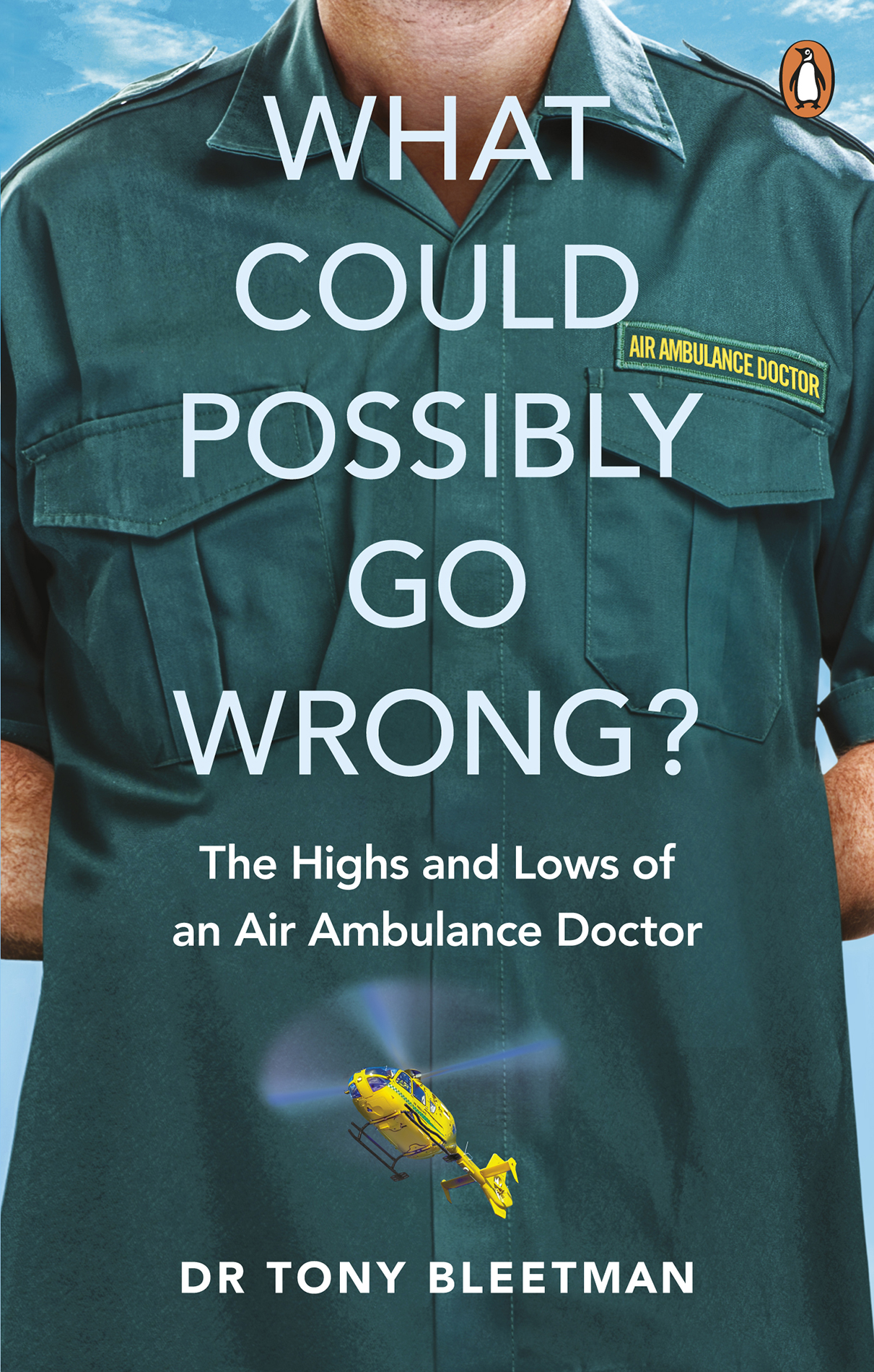

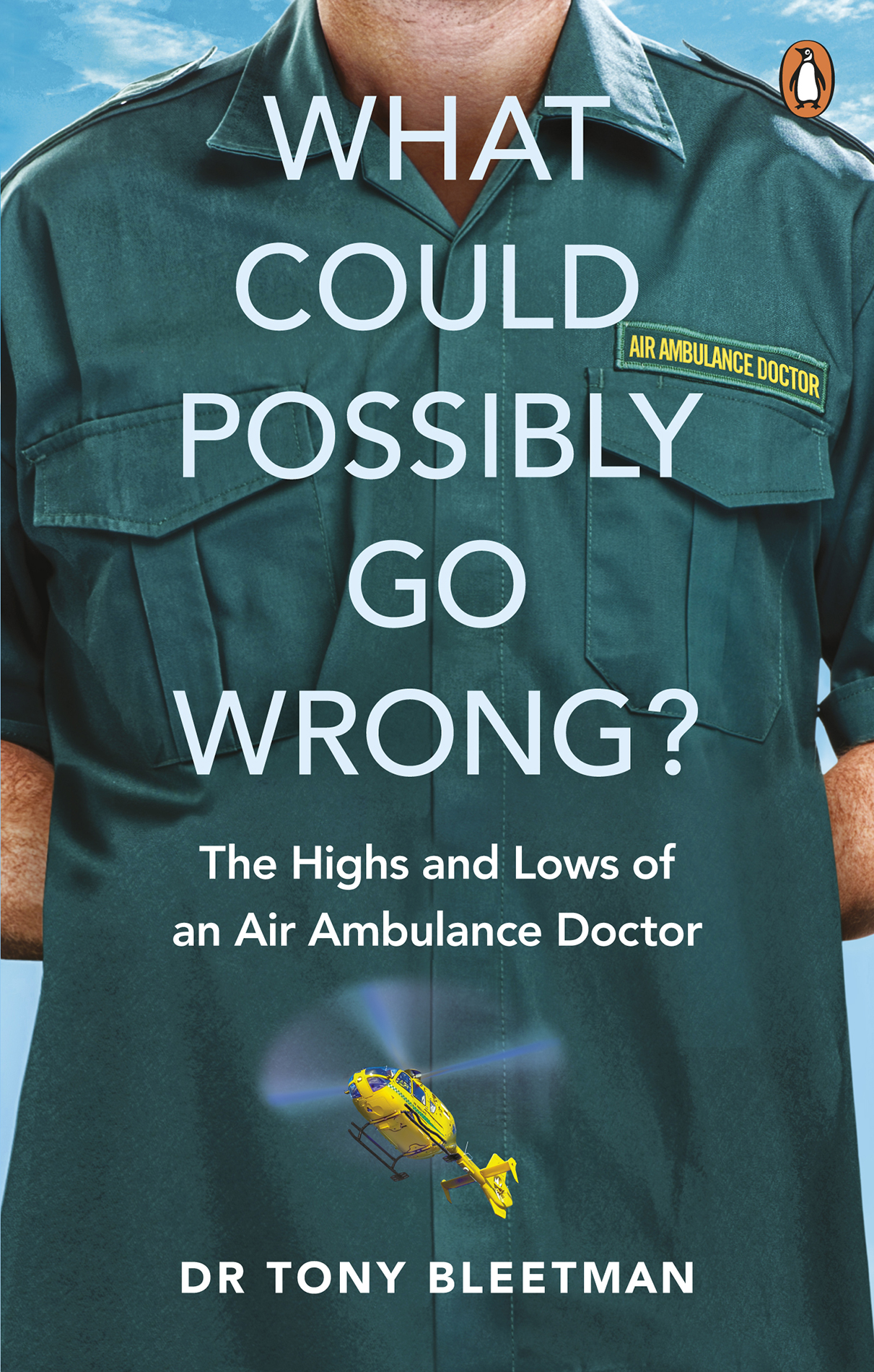

TONY BLEETMAN

WHAT COULD POSSIBLY GO WRONG?

The Highs and Lows of an Air Ambulance Doctor

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Tony Bleetman grew up in London and is a consultant in Emergency Medicine. A former Army doctor and a private pilot, he was one of the first Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) doctors who established the modern air ambulance network. He flew for three air ambulance units, helping to develop the provision of advanced medical care in the field. In 2006, he was awarded the National Life Saver Bravery Award in recognition of his services.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Peter Ryan Boatman QPM

This book is based on the life, experiences and recollections of the author and the extraordinary work of his colleagues. To protect the privacy of others the names of some people and places and some details, dates and sequences of events have been changed and some third-party scenes and actions may be presented as first-hand experiences.

PROLOGUE

The Right Wrong Stuff?

During open-chest resuscitations, Ive held a non-beating, recently stilled human heart in my hands. And, should you ever get to hold one, you will find the human heart to be rubbery and shockingly light considering all the work it has to do: approximately eleven ounces in a man, nine ounces in a woman, one ounce in a wheel clamper.

Occasionally Id get those stopped hearts started again; most times I didnt. Sometimes these operations were carried out on pavements, sometimes in a prison yard, sometimes in a living room. A living room that in turn could become a morgue or delivery suite, depending on whether the patient died or was reborn.

I knew from a very early age that I had to be a doctor. I had always respected the familys GP. Dr Hyman was kindly but firm and very no-nonsense. It was obvious to me even as a young child that this man had great intelligence and compassion. He loved his job and he made me feel better. Each consultation ended with an anecdote, which was about how exciting it was to have studied medicine and become a doctor. His obvious enthusiasm for medicine had a big impact on me. I wanted to be just like him: strong, clever and happy. Even though I was encouraged to go into the familys optician business, I knew that I had to become a doctor, no matter what. Dr Hyman died a few years ago. I wish I could thank him for giving me the inspiration to embark on an exciting, fulfilling and adventurous career with the added bonus of helping people along the way.

My desire to become a doctor was matched only by my desire to become a pilot. My parents told me that as a two-year-old, one of my first utterances was up car as I looked up and pointed at an aircraft. Seems logical to me even now. I saw a vehicle (car) that was up in the sky. Must be called an up car then.

During summer holidays with my grandparents in Oxfordshire, I occasionally saw Concorde flying overhead during her flight trials. I was mesmerised by her beauty and power. My interest in aviation grew and became a little obsessive. I collected pictures and books on aircraft and read everything that I could about the subject. My first flight was in a Vickers Viscount from Heathrow to Jersey on a family holiday. As we boarded, the pilots welcomed us on to the aircraft. The flight deck door was open. I stopped to look at the dials and switches. The captain looked down at me and smiled. He looked so important and suave in his BEA uniform and cap.

The flight was much better than I could have imagined. I still remember looking out the window transfixed by the passing landscape and the clouds. In fact, the flight was far more exciting than the holiday itself. By the age of four I knew that I had to be a doctor and I had to be a pilot.

Here are two facts for you: trauma injuries, whether at home, at work, on the road or through crime, are the largest killer in Britain of people under the age of 40. And all of the 20 or so air ambulance units in this country are run by charitable donations. This means that whenever you hear that distinctive sound of helicopter blades slicing up the sky above you often on the way to one of those trauma injuries mentioned above and you see one of our red or bright yellow metal birds flying by, the jet fuel its running on hasnt been bought by the NHS or the government but from donations given by strangers. And its not cheap: an hours flying time costs about 1,000, so the news that the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service or HEMS, as we like to call it is able to exist solely on the generosity of the public is both brilliant and shocking.

And, to be honest with you, when I tell people what I do, their reaction is that my work is both brilliant and shocking too. I have friends who are not involved in the worlds of either medicine or aviation who just dont know how I can do it. Whether its cutting through the breastbone of a patient so you can plug a stab wound in their heart or barrel-rolling a light aircraft at 5,000 feet, the general reaction is one of disbelief. Im often asked how I could put my life on the line like that, and how I feel about having the lives of other people in my hands.

To answer that question means I have to make a confession: the truth is Im an adrenaline junkie. Sometimes that means piloting my little blue and white Beagle Pup up there where the air is thin. When I flip the plane over so Im upside down, and the green of the earth is suddenly above me and the blue of the sky is under my wings, it feels fantastic. Its freedom.

And then there are the times when Im fighting to save someones life, rather than risking my own. When everything goes right and youre able to help someone in a critical condition when youve genuinely made a difference its that adrenaline rush all over again. Different kind of barrel roll; same feeling.

In his famous book about NASA and jet aircraft test pilots, The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe coined that term to describe that certain something the pilots needed to have in their psychological make-up to be able to do what they did. And this same theme crops up whenever I have to give a talk about my work as an emergency physician: Im often asked what characteristics make a good emergency doctor. I tell people about that strange kind of detachment you need, the distance that all doctors, surgeons and medical professionals must have in order to function calmly while someones life is in the balance.

Maybe there has to be something equally wrong about both doctors and flyers for them to function normally in often very abnormal circumstances; but I would say this in their defence it is, I think, at least the right wrong stuff (if that makes sense).

The right wrong stuff is vital when you get an emergency call-out on New Years Eve and you respond by scrambling into a bright yellow Agusta 109 helicopter, which then screams you across the sky at near-200mph to drop you into a head-on accident crash scene. You find the young driver is so close to death that you have to operate on her immediately while she is still trapped in the wreck; and all the time youre surrounded by the smell of spilt petrol, the sound of fire engine generators and power tools used to cut open the vehicle and you see flashing blue lights illuminating pooled blood. Theres no time for emotion in this sort of scenario, no time for anything but the job at hand. And if I need to be detached from the situation, so be it. Its what makes me good at what I do.

Next page