FOREWORD

Had the two intrepid journalists from the Washington Post, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, not relentlessly pursued the leads they got from a source they called Deep Throat, the world would perhaps not have come to know the full extent of the Watergate scandal that cost Richard Nixon his presidency in 1972. In the past century or so, there have been many path-breaking investigative stories that changed the political landscapes of their countries. Closer home, the Bofors scandalexposed after the Swedish Radio broke the story of kickbacks in the Rs 1437-crore Bofors howitzer dealchanged the political landscape of India in 1989. Needless to say, the country has produced some of the finest investigative journalists who have exposed crimes and corruption in public life.

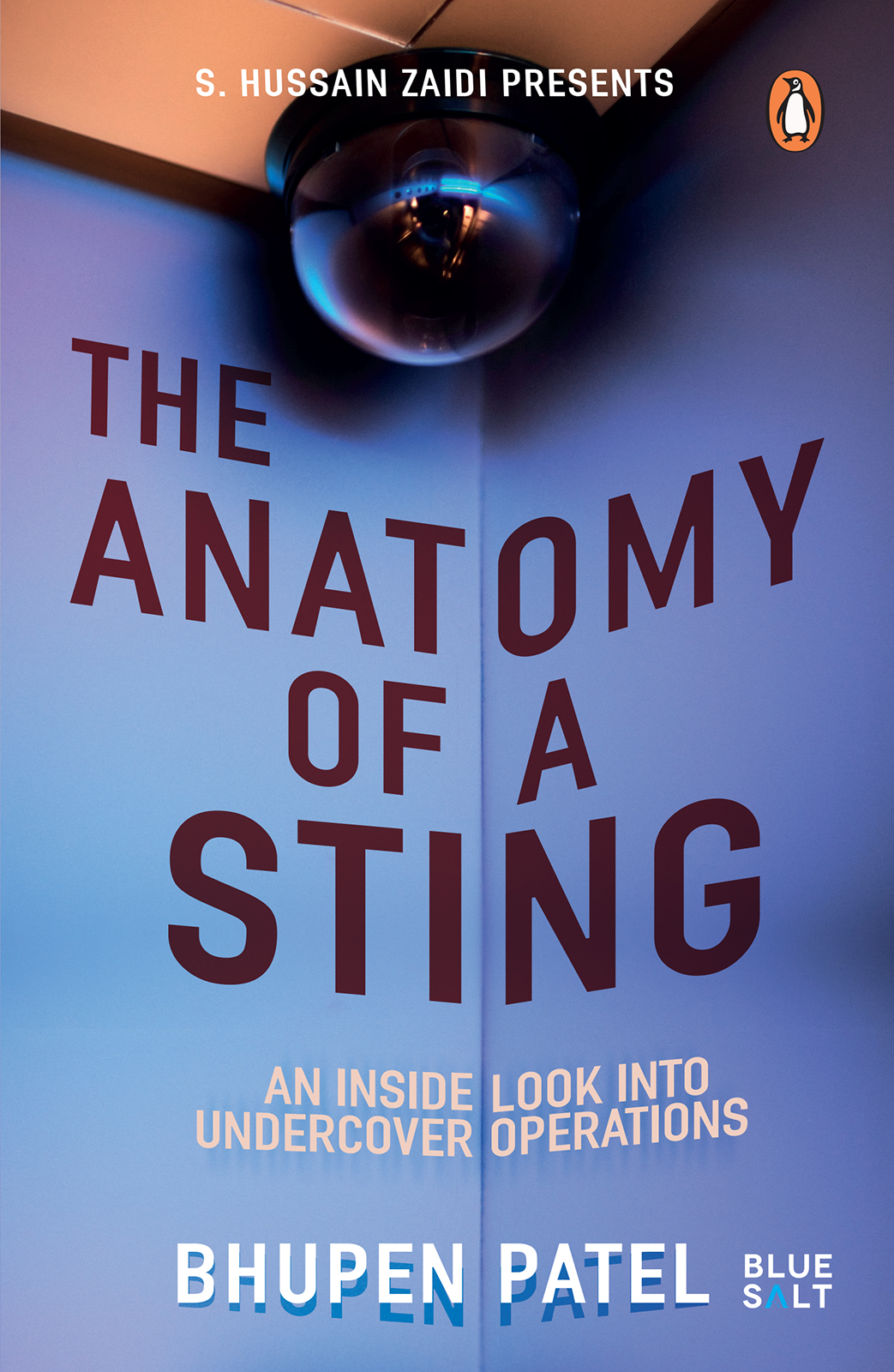

As you leaf through the pages of The Anatomy of a Sting, you will come across tales of grit, gore and grime from the world of crime. These tales, told with all their grey shades, force you to hold your breath, wondering how the journalist pulled off these coups, sometimes putting his team and himself in mortal danger.

But then journalism is no cakewalk. A journalist has to follow the basicswho, what, why, where, when, howwhile pursuing a lead or a story idea. Although all stories, even if they are mundane, require due diligence, investigative journalism requires talent, skill, money and luck. An accountant and a lawyer should not be allowed to have a say before an assignment is complete. An investigative journalist, like me, gets a kick only when an undertaking is accomplished and he breaks the story. As a journalist, if a story does not enthuse you or thrill you, you cease to be a serious muckraker!

For you to crack a story, well, you need adequate planning. This entails cross-checking the facts, budgeting a proposed investigation and working out the pros and cons of every move, including when to exit the scene unscathed if things get too hot to handle. The source is the key to a good lead and needs to be protected at all costs. It may take months for a story to reach its logical conclusion. In case a hidden camera is used when there is no other recourse, a journalist has to get into the skin of the character he is investigating. Apart from these basic ingredients, there has to be a risk analysis in case the journalist is caught with the camera. If his life is in danger, it is judicious to call off the operation at once.

A story narrated in this book exemplifies the risks involved. As it happened, the journalist pursued a tip-off after twin bomb blasts, one in Zaveri Bazaar and the other at Gateway of India, shook Mumbai in August 2003. After making inquiries with the investigating authorities, it was clear that there was more to the story than met the eye. The operation was undertaken to nail the mastermind behind the blasts, who was ensconced in Dubai, although the man who had executed the blasts had been arrested along with his wife, his accomplice. Pursuing a lead, the journalist went to Dubai but landed in a lock-up. In his zeal, the journalist discarded the cardinal principle of undercover investigation: play it discreet. He had to return to India as soon as the Dubai police let him off. Fortunately, his cover was not blown.

Although there are no fixed rules, for it all depends on the circumstances which may take unexpected turns to test your patience or shock you out of your wits, we at Cobrapost follow certain guidelines which every journalist should adhere to.

We are a country of dreamers. Many of us, especially when we are young, are smitten by the Bollywood bug! But very often, many of those starry-eyed youngsters end up being fleeced by conmen on the prowl who lay intricate traps to entice them with roles in films that never materialize. A journalist exposed two such conmen, who with the help of a Bollywood actor, had set up shop to con gullible dreamers. His expose on a mental asylum, showing how easy it was to throw someone hale and hearty into it, reminds me of a similar expose in nineteenth-century New York by the gutsy Nellie Bly, an undercover reporter who spent time in an asylum to tell the world how a perfectly sane person could easily make it to the house of the lunatics and the pathetic conditions prevailing there.

It was a coincidence when the sobbing eleven-year-old Ameena Begum, accompanied by an elderly Arab, caught the attention of an air hostess who raised an alarm. The next morning, in October 1991, the entire nation woke up to the shocking news of poor, underage girls being sold off in marriage to wealthy Arabs. The author also busted one such racket in Mumbai where rich Arabs on a pleasure trip to India married girls of their choice for as measly a sum as Rs 14,000, and after a week or two pronounced triple talaq before boarding a home-bound flight. However, the kingpin of this marriage-for-sex ring, a Mumbai qazi, and his accomplices vanished before the police swung into action. Sadly, such rackets still thrive both in Hyderabad and in Mumbai.

The stories that Bhupen Patel has knitted in this book are his labour of love during his stints with Mid-Day, Mumbai Mirror and NDTV, all in the city that never sleeps, the city which is called Indias financial and business capital, the city which is host to the worlds largest film industry, and the city which breeds crimes and criminals as effortlessly as it harbours a multitude of humanity of every imaginable colour, race and faith. Bhupen now heads the crime team at Mid-Day.

If criminals, racketeers and scamsters abound in our country, so do hard-boiled journalists who sniff out stories and are ready to expose all shady activities in public interest. And then there are journalists who share their dangerous yet fascinating journeys with their readers. This book is all about that.

Aniruddha Bahal

Founder and editor, Cobrapost

INTRODUCTION

Often, conventional and formulaic ways are not sufficient to tell a story. In fact, reporters will vouch for the fact that the more complex and intricate the assignment, the more thrilling and exciting the ride. Sometimes a straightforward approach is not enough to uncover the web of lies and deceit behind a story. Sometimes a journalist has to shatter the conspiracy of silence with a bang and, in the unmasking, he or she might have to walk a tightrope to bridge the distance in an unsavoury manner. Stings are not popular among all journalists, but I feel that for great stories one has to keep reservations on the matter aside and just take the plunge.