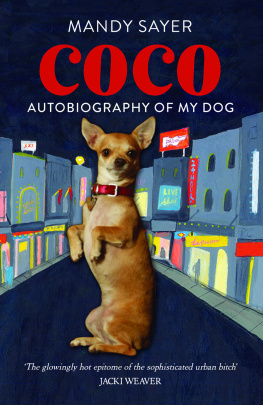

M ANDY S AYER won the Vogel Award with her first novel, Mood Indigo. Since then she has published five works of fiction and six works of non-fiction, including the memoirs Dreamtime Alice, winner of the National Biography Award; Velocity, winner of the Age Book of the Year for Non-Fiction and the South Australian Premiers Award for Non-Fiction; and The Poets Wife, shortlisted for the West Australian Premiers Award. Her study of Romani culture, Australian Gypsies: Their secret history, was published to acclaim in 2017. She lives in Sydney with her husband, playwright and author, Louis Nowra, and their dogs, Coco and Basil.

mandysayer.com.au

Also by Mandy Sayer

FICTION

Love in the Years of Lunacy

The Night has a Thousand Eyes

Fifteen Kinds of Desire

The Cross

Blind Luck

Mood Indigo

NON-FICTION

Australian Gypsies: Their secret history

The Poets Wife: A memoir of a marriage

Velocity: A memoir

Dreamtime Alice: A memoir

Coco: Autobiography of my dog

OTHER

The Australian Long Story, ed.

In the Gutter Looking at the Stars, ed. with Louis Nowra

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Mandy Sayer 2018

First published 2018

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN 9781742236100 (paperback)

9781742244334 (ebook)

9781742248769 (ePDF)

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Nada Backovic

Cover image Adam Knott

Printer Griffin Press

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

This book is printed on paper using fibre supplied from plantation or sustainably managed forests.

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

To Louis, my favourite misfit

Contents

Prelude

I fell in love with my first misfit at the age of three. He was a disabled man in a wheelchair who sold newspapers every afternoon outside the Empire Hotel in Annandale, Sydney. Whenever I glimpsed him in the distance I would break into a run, jump onto his lap and smother him with kisses. I nicknamed him Lurch, after a television character I also loved, the tall, taciturn butler on The Addams Family. In my mind, the two men were one, and whenever Lurch the butler exited a scene on the screen, I would hang out the living room window and strain to see him on the street. Misfits have intrigued me ever since.

Misfits often have a history of trying to fit into the dominant culture, but to an extent have failed or have grown disillusioned. As a child, my father spent the first seven years of his life in hospital, enduring scores of primitive surgeries to mend his cleft lip and cleft palate, and had no formal education (or socialisation) until his release. His concerned parents placed him in a private school, where he was later warned by the principal that if he didnt play football, he wouldnt be able to mix in general society. Already, at the age of nine, hed given up trying to assimilate into general society, preferring instead the solitary study of music. My husband Louis, who at the age of twelve suffered a near-fatal head accident and had to learn to speak again, has often told that when he was a young man he just wanted to be normal, and would study the gestures and habits of other people so as to appear to be one of them.

Exclusion from society can at times be painful, but under the right circumstances it can also become a form of freedom. The disenfranchised create small niches of power wherever and whenever they can and it is within these niches that they exercise imagination, resilience and creativity. For example, I have two elderly cousins brother and sister who have lived together for decades in their late mothers art deco house (see The Hordes). They have also inherited their mothers obsession with hoarding, so much so that they use a Kookaburra stove as a dispensary, and stacks of old newspapers for shelving. Another example would be Don Miller, featured in the essay Flying High, a gifted elderly chemist who would rather cook meth for a Lebanese bikie gang than run his own business, because it satisfied his boundless curiosity. Misfits find ways to take advantage of their outsider status to make more meaningful lives for themselves and others. Misfits dont undermine the status quo; they tend to ignore it.

From my experience, misfits are devoid of self-pity and are usually quite inventive. My younger brother, for example, used to take two breaks a day from his job as a housepainter to perform dialysis on himself with a portable machine in the back seat of his car (further discussed in The Gift of Life). Another example would be Aboriginal Elder Tony Bower, who drives around NSW in a mobile marijuana dispensary, giving away cannabis oil tinctures that he makes himself to sufferers of cancer, multiple sclerosis, depression, diabetes all the while risking arrest and jail. In The Tincture of Health, he claims, Ive explained to the government and the cops that I am Aboriginal and it is against my culture to refuse help or comfort to someone in need.

Misfits usually have no choice but to live within the fissures of modern society, where they largely remain unnoticed and invisible, unless one of them breaks the law too many times. Some, but not all, are damaged either physically, emotionally, or psychologically and find unique ways of coping with their difference.

Occasionally, an outsider status can be conferred on a town or a particular area and unofficially becomes a geographical misfit. The various settings that are referenced in this collection certainly earn this moniker. Darlinghurst and Kings Cross embody tales of transitory lives transgressive writers and transvestite shop keepers; Apia, Samoa, features feral dogs, serial killers, dengue fever and local standover men; New Orleans tells true stories of professional warlocks, tap dancing street kids, and of a city that has the longest social calendar yet shortest lifespan in America.

Misfits are not self-consciously unusual, or deliberately trying to be different. Due to the accidents of birth, class, genetic inheritance and environment, they often have no choice: both nature and nurture conspire to spawn a genuine outsider. My feature-length profile on Nick Cave, for example, did not make the cut for this collection. Sure, Cave is talented, innovative and individual, but any transgressive or misfitting behaviour is likely to be self-conscious and is enacted to polish his bad-boy persona. True misfits rarely worry about reputation or material reward, and tend to live in the present moment.

Next page