Mum and Dad Ron and Mary.

Thanks for everything.

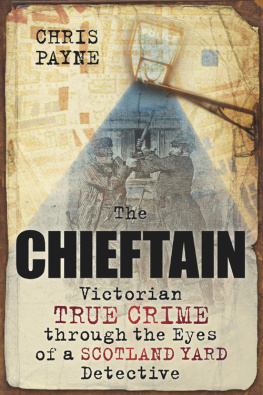

I would like to take this opportunity to thank several people who have given me their time, guidance and advice, which greatly contributed to the completion of this volume. Peter Kennisons unrivalled records of the history of the Metropolitan Police, its officers and police stations have allowed me to delve much deeper into the lives of some of the characters in this book. Charlotte Bakers professional editing skills were a godsend together with the photographic skills of Guy Pilkington.

I would also like to thank the staff of Kensington and Chelsea Local Archives, especially David Walker and Isabel Hernandez for their support, Amy Gregor from brightsolid Newspaper Archive Limited, and finally Cate Ludlow, my publisher, for taking a chance.

It is long since the public have been startled by news of a crime so horrible in all its features as that of which we placed a report before our readers yesterday. We need not apologise for calling attention to it in this place, because, whoever may be the guilty parties, there can be no doubt of the facts, which create an absolute certainty that two of the most horrible murders have been committed of which we have any record

Chelsea has had the good fortune not to be associated with acts of a criminal character and the fact that it is the scene of the present tragedy is somewhat more remarkable on that account.

The Morning Advertiser , Saturday, 14 May 1870

CONTENTS

L ondon in 1870 was developing at an alarming rate; dozens of small towns and villages were being amalgamated to form the greatest industrial city in the world. Slums were torn down and the poor forced further east, leaving the City of London and the west ripe for development. The worlds first underground railway was nearing the end of a decade of operation and continuing to expand, snaking its way across Greater London. Queen Victoria had been on the throne since 1837 and during her reign Britain led the industrial revolution and extended its reach across the civilised world.

The village of Chelsea began life during the Saxon period and gained its name from the Saxon words Cealc (chalky) and Hythe (a landing place for boats). It is situated on the north bank of the River Thames, some 3 miles from Westminster; the Thames has been an important transport artery for London over many centuries, so a location as strategic as Chelsea would always be ripe for development when the ever-growing capital spread westwards. From the Middle Ages through to the nineteenth century Chelsea was largely occupied by market gardens, but its clean air and close proximity to Westminster attracted the wealthy. Sir Thomas More (14781535), Lord Chancellor to King Henry VIII, moved to Chelsea in 1520 and was often visited by Henry when the king travelled to Hampton Court. Sir Christopher Wren built the Royal Hospital between 1682 and 1689. Sir Hans Sloane purchased land here in 1712, eventually becoming Lord of the Manor of Chelsea; Sloane is commemorated in the naming of several Chelsea landmarks such as Sloane Square and Sloane Street. By the early 1800s the population of Chelsea village had risen to 1,500, making it equivalent to a small town.

Kings Road had a defining part to play in the development of modern-day Chelsea. It was built for the private use of Charles II to travel easily between central London, Kew and Hampton Court Palaces. Some of the local nobility were allowed to use the road for a fee, of course. The 2-mile stretch was finally opened to the public in 1830 and this signalled the development of the more familiar Chelsea we know today. A building boom followed in the first half of the nineteenth century that saw the completion of several Kings Road squares: Paultons, Oakley (renamed Carlyle), Trafalgar (renamed Chelsea), Wellington and Markham. The development of Chelsea was a great investment opportunity for any Victorian entrepreneur with spare cash.

Before 1870 violent crime in Chelsea was almost unheard of; this area was not like the dark, dank, filthy streets of Whitechapel, which would, in eighteen years time, harbour a killer of infamous savagery. But in May 1870 the attention of Londoners and others across the country would be drawn to their newspapers as the media of the day reported, in gruesome detail, two horrific murders that shook the residents of this quiet London suburb to the core. Chelsea residents suddenly realised that no one was safe from violent crime.

The Reverend Elias Huelin, born on the predominantly French-speaking Channel Island of Jersey on 19 June 1785, was a curate at the French Protestant church in Soho and assistant chaplain at West London Cemetery (now the Brompton Cemetery). It is unclear when Huelin travelled from Jersey to England; however, shortly after his arrival he purchased a farm in Navenby, Lincolnshire. For some years he worked nearby in Sleaford and was a curate at Evedon. Huelin moved to London and the farm at Navenby was placed under the management of local resident Mr Spafford of Boothby. The earliest record of Huelin living in London can be found in the electoral registers for New Brompton which records him as a resident of No. 5 Seymour Place (now Seymour Walk), Brompton, from 1851 to 1865. The 1861 census (the first to record all occupants of the property) confirms Huelins residence there along with his housekeeper Ann Boss. Boss originated from the Lincolnshire village of Witham South, where she had been raised by her father, a blacksmith, and her mother. The electoral register for 1865 reveals Huelins extensive property portfolio for the first time as he evolved from a man of God to a capitalist; he is shown as leaseholder for Nos 4, 6, 8 and 9 Seymour Place. By 1867, the electoral register reported Huelin as living at No. 24 Seymour Place. It was at about this time that he started to buy larger, grander properties in the more desirable areas of Chelseas Kings Road: Paultons Square (Nos 14, 15 and 32) and Wellington Square (No. 24). By May 1870, Rev. Huelin was living permanently at No. 15 Paultons Square, a large terraced house on the squares west side, still with his long-term housekeeper. Huelin also kept a small dog, which he would often take on his rent-collecting rounds.

The premeditated and murderous events that unfolded during May 1870 have gone down as the most shameful and shocking in Chelseas history. This book examines the events of this period using eyewitness accounts and legal records. What follows is a tale of greed, cruelty and violence which demonstrates a complete disregard for human life. The outcome is a real-life plot that has impersonation and mystery at its core; it is a story that could have come from the pen of contemporary crime writers of the day such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Louis Stephenson or Wilkie Collins.

Contemporary records from the period 1870 used in this book include newspaper reports, illustrations and other sources. Some of these reports use different spellings of the names of the characters featured in this book; to maintain continuity I have used the spelling of the names recorded in official documents (death certificates, census returns and the England and Wales National Probate Calendar) that would have been supplied by the people themselves or close relatives.

Next page