Richard Schickel - The Actors

Here you can read online Richard Schickel - The Actors full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: New Word City, Inc., genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Actors

- Author:

- Publisher:New Word City, Inc.

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Actors: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Actors" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

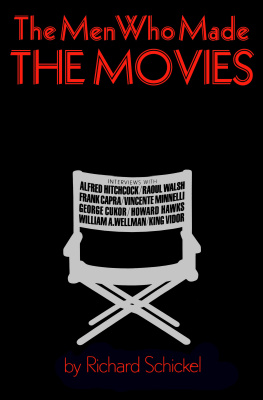

Here, Times legendary film critic Richard Schickel profiles seven extraordinary actors, reading between their well-spoken lines: Humphrey Bogart, Marlon Brando, James Cagney, Charlie Chaplin, Gary Cooper, Douglas Fairbanks Sr., and Sir Lawrence Olivier. All of their lives, Schickel writes, could be made into an epic film.

The Actors — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Actors" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Ironies abound in the life and work of Humphrey Bogart. Among the more curious of them is this: The longevity of his stardom was less than that of any of the dominant movie personalities with whom he must logically be compared. Whether one dates his emergence as a figure to be reckoned with from High Sierra or The Maltese Falcon in 1941 or from Casablanca two years later, the fact is that he matched his own definition of stardom you have to drag your weight at the box office and be recognized wherever you go - for only about a decade and a half. That is less time than most of his contemporary peers Astaire, Cagney, Cooper, Gable, Grant, Tracy, Wayne - enjoyed that status.

Related to that irony is another, larger one. Despite the relative brevity of his ascendancy, no star of his era (possibly excepting Cary Grant, who, despite his retirement from the screen, continued for decades to astound us with tantalizing glimpses of his gracefully aging and always enigmatic manner) remains such a lively presence in our imaginations.

It is true, of course, that Bogart was the first great figure of his generation of stars to die, and premature death enhances, however briefly, a public figures hold on his public, encouraged as they are by the cheap press to ponder sentimentally all highly visible evidence of lifes shocking mutability. But Gary Cooper and Clark Gable followed only a little later, and also before their time, and they do not share the powerful hold on posterity that Bogart does. Like other stars of that era, they are mostly treasured nostalgically by older people, for whom they remain the unsinkable dreamboats of adolescence, the first, and therefore the best, repositories of our earliest romantic fantasies. Our children may have learned a respectful thing or two about these figures from television, but they do not find them totally awesome (to borrow teenage Americas highest current accolade). Their tendency is to nod politely when the old guys are mentioned - and start sinking down on their spines or edging out of the room.

With Bogart, though, it is different, especially if they are middle-class and collegiate. To them, he is alive as no movie figure not of their moment is. More than four decades after his death (in January 1957), he continues to speak for them and to them. They think they know him as they know themselves, as a man grappling with what they have just learned to call the existential issues.

Herein lies the largest irony Bogart presents to us. For this is the second case of mistaken identity his career offers, the first having been that he was a tough guy. Always, it seems, the relatively simple truth about the man eludes us; always, it seems, we have gone thundering past the intersection where personal history and screen character meet and mutually inform each other. It is my purpose here to linger at that crossroads and contemplate the evidence about who he was and what he was - evidence which he left plentifully scattered about in plain sight.

We may profitably begin at the beginning, with the first and simplest of his movie images, that of the entirely charmless tough guy, sort of a second-string George Raft (unimaginable as that status now seems). He was thrown into competition for roles with Raft at Warner Brothers because Bogart achieved his first movie prominence playing the gangster Duke Mantee in the mummified adaptation of Robert Sherwoods ridiculous play The Petrified Forest. For six years after, the studio kept him close to what it quite thoughtlessly, quite unobservantly assumed was his type. Bogart, not unnaturally, objected to this kind of casting, mostly because he was really rather bad, often visibly uncomfortable, in these roles. On the other hand, he also found it amusing, because it was so wildly misleading, to play a hard case off screen. He had a fondness for a certain type of newspaperman, hardened drinkers, and sentimental cynics, and to them he was astonishingly voluble, snarling sardonically for attribution, about his profession and the way the movie business was conducted. Since he was an alcoholic married to an alcoholic in these years (his third wife, the sometime actress Mayo Methot), their drunken battles in public and at the home to which the police were frequently summoned to quell disturbances also lent credibility to the image of a man who, according to what seems a reliable accounting, was hanged or electrocuted eight times, sentenced to life imprisonment nine times, and riddled by bullets a dozen times in his first forty-five movies.

Since even after he was rescued from the supporting roles and B picture leads in which he suffered these indignities he continued to play men who found themselves on the margin of legality (and sometimes on the margin of sanity), and since he did not grow notably less outspoken or more sober in his nocturnal recreations, this aura did not entirely dissipate in later years. Indeed, to the majority of his contemporaries in the audience, toughness, even after it was enlisted in idealistic and romantic causes during the war, remained an essential element - perhaps the essential element - in his persona. Raymond Chandler, who knew something about this subject, spoke for the generation that met him first as a mug when he wrote: Bogart can be tough without a gun. Also, he has a sense of humor that contains that grating undertone of contempt. Ladd [who emerged as a star of a similar kind at the same time] is hard, bitter and occasionally charming, but he is after all a small boys idea of a tough guy. Bogart is the genuine article.

If there had been nothing more to him than that, Bogart would probably not have been a star - not for any length of time, anyway - and he certainly would not have become a legend for later generations to moon over. (For that matter, Chandlers own great creation, Philip Marlowe, whom Bogart successfully impersonated once he had found his own character, would not have become an immortal fictional figure if he had been merely tough.)

No, Bogart had to subtract a little something from that vulgar image - and add a great deal to it. This he began to find the opportunity to do in Sierra and Falcon, but unquestionably his authority as a screen presence, both during the rest of his career and posthumously, radiates outward from Casablanca. It is certainly not his best performance - he stretched more in others, revealed more of himself in still others - but it is good. And it is good not because he is embodying that congeries of modern philosophical ideas that have since been imputed to Rick/Bogie, but simply because Humphrey Bogart, the actor, is easeful here, instinctively at home with his character in a way that he only rarely had been before, and never as fully as this.

That kind of comfort with a character, that kind of blending of a factual self with a fictive creation, in which neither the performer nor the audience is entirely aware of where the one ends and the other begins, is extraordinarily rare. But it is a basic requirement for screen actors working at the star level and hoping to stay there for a while.

Many people as gifted as Bogart (or more so) never find the role in which that connection can be made. And as we have observed, and will have reason to observe again, he had to wait a long time in frustration before he could make it. In any event, one does not take up residence in a role, as Bogart did when he got under Rick Blaines skin, through an intellectual process.

All the imputations to the contrary, all the attempts to claim Rick Blaine and Humphrey Bogart for the party of Sartre and Camus needlessly complicate what turns out to be, on not-too-arduous examination, a fairly simple identification between actor and part. These claims and imputations are rationalizations for the fad that was created around

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Actors»

Look at similar books to The Actors. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Actors and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.