MARTIAL

MARTIAL

THE MAKING OF MANCHESTER UNITEDS NEW TEENAGE SUPERSTAR

LUCA CAIOLI

and

CYRIL COLLOT

Translated from the Italian and the French by Laura Bennett

Published in the UK and USA in 2016

by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

7477 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Grantham Book Services,

Trent Road, Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500,

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa

by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

7th Floor, Infinity Tower C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

Distributed in Canada

by Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300, Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

Distributed in the USA

by Publishers Group West,

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

ISBN: 978-178578-097-4

Text copyright 2016 Luca Caioli and Cyril Collot

English language translation copyright 2016 Laura Bennett

The authors have asserted their moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in New Baskerville by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

About the authors

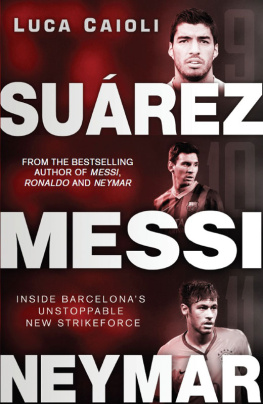

Luca Caioli is the bestselling author of Messi, Ronaldo, Neymar, Surez and Balotelli. A renowned Italian sports journalist, he lives in Spain.

Cyril Collot is a French journalist. He is the author of several books about the French national football team and Olympique Lyonnais. Nowadays he works for the OLTV channel, where he has directed several documentaries about football.

Chapter 1

Soaring towers

Why are the people who live in Les Ulis so surprised by the Bergres Towers? Why do they always ask why sixteen-storey buildings have been placed so close together when there is so much space around them? The answer offered by a welcome pamphlet distributed to new arrivals is simple: The architects had no choice. They had to fit 10,000 homes on 200 hectares, not a handful of detached houses scattered across a park.

Anthony Martial grew up in one of the soaring Bergres Towers, white, grey and pale coffee-coloured high-rise blocks that sprout up side by side in the centre of Les Ulis. We are twenty kilometres south east of Paris, in the dpartement of Essonne, le-de-France. On 17 February 2017, Les Ulis, caught between the A10 motorway and the 118 trunk road, will celebrate the first 40 years of its existence.

The story of Les Ulis began in 1960, when a ministerial decree authorised the urbanisation of an area between the towns of Bures-sur-Yvette and Orsay. It was intended to house employees, managers and researchers working for the Atomic Energy Commission, the large companies at the Courtabuf business park, and the Universit Paris Sud. In 1965, work started on the grassy fields used at that time for cultivating wheat, beetroot, strawberries and vegetables. France was experiencing a time of pronounced economic growth and improved living conditions during the period that would come to be known as the Trente Glorieuses. Robert Camelot, Franois Prieur and Georges-Henri Pingusson, the urban planners who designed Les Ulis, were inspired by the ideas of Le Corbusier: housing complexes, squares designed as terraces, internal streets for shops, and the separation of traffic flow, with walkways for pedestrians and streets for cars. It was a raised or elevated form of urban planning, an architecture of growth found in suburbs all over France. In 1968, the new developments first inhabitants moved into the Bathes and Courdimanche districts, although some buildings were yet to have running water. Eight years later, on 14 March 1976, the citizens of Bures-sur-Yvette, Orsay and the new town were called upon to choose between three proposals in a referendum: maintaining the status quo, the current administrative situation at that time; opting for Bures-sur-Yvette and Orsay to be merged to encompass Les Ulis; or creating a new, third commune called Les Ulis. The winner, by a very slim margin, was the third option, and, on 17 February 1977, the 196th commune of Essonne, Les Ulis, officially came into existence. Once again, the welcome pamphlet explains that its name comes from the Latin verb uller, which means to burn. The name of the town is derived from the ground on which stubble was burned to make fertiliser.

In March 1977, Paul Loridant, a 28-year-old socialist, was elected mayor. His mandate would be renewed six times: he spent 31 years governing the town. The former Banque de France employee and one time senator for the Mouvement rpublicain et citoyen is now 68 and currently the deputy mayor in charge of finance and social affairs.

He remembers: When I arrived, the town was a huge open-air construction site. There was still plenty of building to be done: the market, post office, town hall, the Boris Vian cultural centre, but there were already 20,000 inhabitants, people from all over France who came to work elsewhere in the region, or in Paris. Eighteen per cent of the inhabitants were back then, and still are, of foreign origin.

Portuguese, Moroccans, Algerians, Tunisians, immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa (Mauritania and Mali), Runion and the Antilles (Guadeloupe and Martinique in particular). The population grew rapidly until 1982, when the inhabitants of Les Ulis reached almost 29,000, but this was followed by a slow demographic decline and consequent decay. Today, the municipality is home to barely 25,000. The percentage of young people living in the town has also fallen significantly. Why? According to Paul Loridant, the unresolved problem with Les Ulis is the integration and social evolution of a population of humble origins: We have not been able to stop people leaving when their standard of living improves and they start climbing the social ladder. They prefer to move to neighbouring towns, such as Orsay or Limours, or closer to Paris, where they think they will have a better life, where society is more mixed. In Les Ulis, where we have more than 50 per cent social housing, those who leave are replaced by new immigrants.

Not everyone agrees with this view. Many mention social problems, delinquency and crime. This isnt the Bronx, replies an indignant Benot. This is a quiet town. Its nothing like some of the other towns around here. In 2005, during the banlieue riots, nothing happened here. There werent any clashes or raids.

Difficult neighbourhoods? No, there arent any, confirms Yassine. Everyone knows everyone here and we respect one another. Were half an hour from Paris and we have plenty of advantages without any of the inconvenience. This is a cosmopolitan town that produces rappers and footballers, nothing else. But the local newspapers talk of drug trafficking, cannabis in particular. They say that Les Ulis has ended up on the liste rouge of problem towns and cities. They report incidents between youths and the police, as in the summers of 2009 and 2015. Paul Loridant admits: Yes, there have been incidents, but never anything serious and certainly no more than in other cities in the Paris banlieue. As any good administrator would, the deputy mayor stresses the positive steps taken in terms of culture and infrastructure. He talks about kids from seriously underprivileged families in Les Ulis who have gone on to become university professors and leading researchers. Above all, he illustrates the current redevelopment, a genuine reconstruction to adapt the town to the demands of modern life. An ambitious project to revamp a style of urban planning that has failed to stand the test of time. A stroll around the city centre near the town hall, esplanade and market is all it takes to grasp that this is a place undergoing a transformation. Beneath the low-flying aircraft coming in to land on runways three and four at the nearby Paris Orly airport, they are working everywhere you look to change the face of Les Ulis. They are even re-cladding the towers. That one there, at the bottom, near the park, the Tour Janvier, thats where Anthony lived, says Jean Paul. He points to a sixteen-storey high-rise block like all the others, named after the months of the year and separated by gardens and leafless trees.

Next page