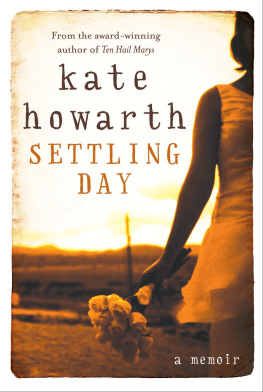

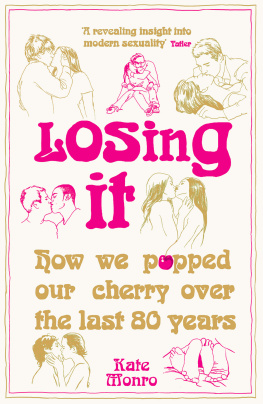

Kate Howarth was born in Sydney in 1950 and grew up in the suburbs of Darlington and Parramatta, and far western New South Wales. She was forced to leave school at fourteen and an eclectic career followed; she has been a factory worker, an Avon lady, corporate executive and restaurateur, to name a few. At the age of fifty-two she began writing her memoir, Ten Hail Marys , which in 2008 was shortlisted for the David Unaipon Award for Indigenous Writers. In 2010, it was shortlisted for the Victorian Premiers Literary Award for Indigenous Writing and won the Age Book of the Year for Non-fiction. Kate is proud of her connection to the Wiradjuri and Wonnarua people of New South Wales.

Kate Howarth was born in Sydney in 1950 and grew up in the suburbs of Darlington and Parramatta, and far western New South Wales. She was forced to leave school at fourteen and an eclectic career followed; she has been a factory worker, an Avon lady, corporate executive and restaurateur, to name a few. At the age of fifty-two she began writing her memoir, Ten Hail Marys , which in 2008 was shortlisted for the David Unaipon Award for Indigenous Writers. In 2010, it was shortlisted for the Victorian Premiers Literary Award for Indigenous Writing and won the Age Book of the Year for Non-fiction. Kate is proud of her connection to the Wiradjuri and Wonnarua people of New South Wales.

For my children and grandchildren

My son, Adam, aged eighteen months.

Hell get over it

Where to, love?

My mind was blank as I stared through the wire mesh screen. The ticket seller at Lidcombe Station repeated his question, drumming his fingers impatiently on the counter.

Central Station, please, I mumbled, slipping a two dollar note into the brass metal tray.

Single or return?

Single, thank you.

Sydneys Central Station isnt so much a destination as a hub for interstate and suburban trains and buses to converge. Id think about where I was going when I got there. As I waited on the platform I noticed a man standing nearby reading a newspaper. The front page spread featured a beachscape with the headline: Prime Minister Harold Holt, disappeared presumed drowned.

It had only been four weeks since Id left my husband, John McNorton, but being separated from my infant son, Adam, whom I couldnt take with me, made it seem like an eternity. I hadnt gone far in that time, just two suburbs in fact, but without my son it may as well have been to the ends of the earth. Not an hour had gone by when I didnt think about the last time we had been together, his angelic face turned up to mine. I had stood next to his cot and promised that Id be back as soon as I found a job and was settled. Id found a job within the month, but without Adam I was never going to be settled.

A few days earlier Id called John at work and told him that I wanted to meet. If necessary, I was prepared to go down on my knees and beg him to take me back. If that wasnt possible I was hoping to arrange to see Adam every weekend.

We met under the Lidcombe railway bridge, a short walk from where I was staying. John drove a distinctive Volkswagen and was waiting for me. Hello, John, I said, getting into the passenger seat. He looked straight ahead as he lit up a cigarette. As trains roared overhead and monster trucks rocked us from side to side in the slipstream, my fate and that of my one-and-a-half-year-old son was decided.

Its that Peter guy isnt it?

No, I said, unable to look at him.

Yes it is, he grinned.

Please John, let me come home, I begged. Or at least let me see Adam. Im going insane.

No way, he replied, smugly.

A freight train rumbled overhead. My mind raced in all directions. How did he know about Peter? Then it struck me. Johns father had very good connections with the Parramatta police. On the night I had left John I caught a taxi to Peters flat in Lidcombe. A couple of weeks later two uniformed coppers had knocked on the door wanting to speak with a Kay Howarth, in connection to stolen goods. Surprised and intimidated, I stood back and let them into the flat, eager to cooperate and establish my innocence. They made a thorough search of the bedrooms and enquired after the males occupying the premises. It wasnt until after theyd gone that I wondered how they knew my name.

Sitting in the car next to John I felt my anger rise. Id been a sixteen-year-old unmarried mother when my son was born. For five months, during my confinement at St Margarets Home for Unwed Mothers, Id fought the nuns to prevent my son being taken for adoption. You cant afford to keep this child, I was told time and time again, we have a wealthy family waiting to take him.

It was true my family had abandoned me and I had no means of support. But I was sixteen and coming from a very primal place with regard to my baby. It was the first time in my life that I had any power and I was going to use it to stop them taking him. How would we live? I had no idea. All I knew for sure was that no one would love my son as much as I did and I didnt care how wealthy they were. Every night I got down on my knees and prayed to the Virgin Mary to send us some help.

John and his family had known I was at St Margarets. They too had expected me to give up my baby for adoption, and never hear from me again. At the eleventh hour and, it seemed, by divine intervention, my Aunty Daphne had heard of my plight and intervened. It was quite ironic that the one person in my family with the least capacity to help was the only one who reached out. But Daphnes situation was very complicated and there was a limit to how much assistance she could provide in the long term.

In order to keep my son I was railroaded into marrying John. I soon discovered the haste to get us to the altar had been motivated by a threat of carnal knowledge, being brought against John by my grandmother, a crime which carried a three-year prison term. After the police interviewed me and learned of our plans to marry we heard no more of it.

During the twenty months we were together, John and I had lived in a rough industrial suburb, with no phone, no transport and I didnt have enough money to dress myself or my son. I had felt isolated and was struggling to cope, while my husband, seemingly oblivious to my circumstances, squandered his money on various hobbies. At one time he purchased a second car, an FJ Holden, and while he tinkered in the garage with his mate Graham, I made clothes for our baby with material cut from his old clothes.

John sat with the cigarette clamped between his teeth, blowing smoke in my face. I need to get back to work, he said, bringing me back to the present.

What about Adam? I pleaded. He needs his mother.

Hell get over it, he said, starting up the engine. As I turned and opened the passenger door, he added, And dont think of going to Aunty Daphne or Uncle Stan, they want nothing to do with you.

Please, John, I sobbed, if you let me explain what really happened, you will understand why I had to go.

He shook his head and revved the motor. As he drove away I felt as if the lifeblood was being drained from me. A truck roared past and the male passenger in the car behind whistled as the wind caught my skirt sending it flying up over my knees. I felt as putrid as the filth being kicked up from the road, with my grandmothers prophecies ringing in my ears. Youll go onto the street and hawk your fork, just like your mother.

Enraged that he could threaten to take my son, I made an appointment in my lunch hour to see a solicitor in Rydalmere who left me in no doubt about where I stood. As I took a seat, I glanced at the statue of the Virgin Mary on his desk, lined up next to the photographs of his children.

Your husband can turn you out with just your clothes and, if you have one, your sewing machine, he told me, dismissing the notion that I had a leg to stand on when I revealed that after leaving my husband I had been living in a flat with two men Peter Ashton, a former boyfriend who had helped me to get away, and his good mate Deanie.

Kate Howarth was born in Sydney in 1950 and grew up in the suburbs of Darlington and Parramatta, and far western New South Wales. She was forced to leave school at fourteen and an eclectic career followed; she has been a factory worker, an Avon lady, corporate executive and restaurateur, to name a few. At the age of fifty-two she began writing her memoir, Ten Hail Marys , which in 2008 was shortlisted for the David Unaipon Award for Indigenous Writers. In 2010, it was shortlisted for the Victorian Premiers Literary Award for Indigenous Writing and won the Age Book of the Year for Non-fiction. Kate is proud of her connection to the Wiradjuri and Wonnarua people of New South Wales.

Kate Howarth was born in Sydney in 1950 and grew up in the suburbs of Darlington and Parramatta, and far western New South Wales. She was forced to leave school at fourteen and an eclectic career followed; she has been a factory worker, an Avon lady, corporate executive and restaurateur, to name a few. At the age of fifty-two she began writing her memoir, Ten Hail Marys , which in 2008 was shortlisted for the David Unaipon Award for Indigenous Writers. In 2010, it was shortlisted for the Victorian Premiers Literary Award for Indigenous Writing and won the Age Book of the Year for Non-fiction. Kate is proud of her connection to the Wiradjuri and Wonnarua people of New South Wales.