Also by BRUCE SHAW

The Animal Fable in Science Fiction and Fantasy (McFarland, 2010)

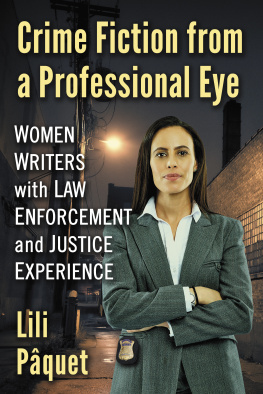

Jolly Good Detecting

Humor in English Crime Fiction of the Golden Age

BRUCE SHAW

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1396-3

2014 Bruce Shaw. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: detective and background images (iStockphoto/Thinkstock); fingerprint 2013 Shutterstock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To the memory of

Susan Vos

Abbreviations

ABC Australian Broadcasting Corporation

COD Australian Concise Oxford Dictionary

OED Oxford English Dictionary

SBS Special Broadcasting Service (Australia)

Preface and Acknowledgments

This book is an appreciation of selected authors who make extensive use of humor in English detective/crime fiction. Works using humor as an amelioration of the serious have their heyday in the Golden Age of crime writing but they belong also to a paradigmatic tradition recognizable to this day. When I began the project I thought that the field would be conveniently narrow, that very little humor would be found in crime novels. It seemed a contradiction in terms. I was wrong. There is an identifiable lineage or stream of humorous writing in crime fiction that ranges from mild wit to outright farce, burlesque, even slapstick. In my previous book, The Animal Fable in Science Fiction and Fantasy (221222), I planted the seeds of this new project by mentioning the mystery story, melodrama and the crime novel, directions in which my mind was already heading. Personal choice played a large part, often facilitated by moments of serendipity.

A mix of entertainment with instruction is an identifiable tradition in English letters. David Lodge in Consciousness and the Novel (163) discusses early works that challenge, disturb and entertain, adding (164):

In combining elements of comedy, often of a robustly farcical kind, with satirical wit and caricature, in order to explore social reality with an underlying seriousness of purpose, Evelyn Waugh belonged to a venerable and peculiarly English literary tradition which we can trace back through Dickens and Thackeray, Smollett, Sterne, and Henry Fielding [163164, my emphasis].

English crime fiction partakes of this, most obviously because the greater number of its practitioners are raised in the mainstream literary tradition, only that they turned their skills to detective fiction. They are the humorists of the genre, called farceurs by Julian Symons who describes them as belonging to the Farceur school, of detective novelists (247). I prefer to call them humorists and the school to which they belong as their tradition because their joking is not only through farce but makes use of other modes of humor as well.

Close reading is a venerable tool dating from the 1930s with F. R. Leavis and I. A. Richards. It is defined by M. H. Abrams as the detailed and subtle analysis of the complex interrelations and ambiguities (multiple meanings) of the components within a work (223, his emphasis). The approach is also called explicationdevelopment and clarification of the meaning and implication of an idea or principle (COD)and includes paying attention to figures of speech and ways by which a tale hangs together in its structure, and the meanings it conveys. But we should not lose sight of character, thought and plot, which provide the context in which the identification of metaphors and their use and meaning in a text otherwise is lost. In the more traditional Australian university departments, a standard approach is first to provide a potted biography of the author under discussion, sometimes to outline the plot, next to move on to character, and then to themes and literary devices that help make it all appear real or at least plausible, where the principle called suspension of disbelief enters in. This is how lectures were presented when I studied English at the University of Western Australia as a first year undergraduate in 1964 and, although my professional work took a different turn, the attractions of that approach stayed with me.

The other part of the procedure is to embed close reading within the form of a review essay. Walter Murdoch defines the essay as a quiet talk, reflecting the personal likes and dislikes of the author (103), marked thus by a degree of informality. Abrams notes a distinction between formal and informal essays in which the formal essay, which is comparatively impersonal, discusses a topic with some authority and in an orderly fashion, whereas the informal essay is more loosely constructed and deals with everyday matters (56). Both usages, however, do not claim to be exclusive in and of their selves. Similarly, Chris Baldick says that as a minor literary form, the essay is more relaxed than the formal academic dissertation (75).

This overview, then, is a cross between formal and informal as I reflect upon humor balanced between the serious and non-serious, exemplified by a sampling of individual works that I see as primary sources: the novels, novellas and short stories of a particular author, and autobiographical works that are by definition primary because they are personal documents. Biographies, on the other hand, I regard as secondary sources because they are written second hand while often relying heavily upon primary sources such as letters and journals. They can be critical or non-critical, balanced or leaning towards hagiography. The same goes for literary criticism: reviews in newspapers, journals and books, as well as commentaries on authors or their works. They are my secondary sources.

The internet is a comparatively new resource that offers material equally as useful as in more conventional print media. In the last fifty years there has been an explosion of knowledge, now more easily disseminated not only by good quality books but also through the World Wide Web. Googling has become part of our language. Wikipedia, begun in 2001, improves steadily in quality. I refer to it as I do for more traditional sources in print and manuscript, gauging the authority with which it speaks, including its accuracy, by cross-referencing where possible with other sources. As the publishers of Wikipedia say in their disclaimer: Wikipedia articles should be used for background information, as a reference for correct terminology and search terms, and as a starting point for further research. In their citations page they add a warning to budding students: Most educators and professionals do not consider it appropriate to use tertiary sources such as encyclopedias as a sole source for any informationciting an encyclopedia as an important reference in footnotes or bibliographies may result in censure or a failing grade. I cannot agree. In the world of literary criticism where ones opinion may be virtually as good as anothersdepending upon the strength of their logicreaders must judge for themselves and in some circumstances an encyclopedia entry may be useful. The warning is not to use Wikipedia and other depositories of knowledge as ones only source.

Next page