This collection is comprised of works of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors imaginations. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Published by Akashic Books

2010 Akashic Books

Series concept by Tim McLoughlin and Johnny Temple

Moscow Noir map by Sohrab Habibion

ePUB ISBN-13: 978-1-936-07081-7

ISBN-13: 978-1-936070-06-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009939039

All rights reserved

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

info@akashicbooks.com

www.akashicbooks.com

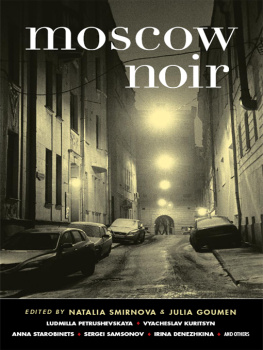

ALSO IN THE AKASHIC NOIR SERIES:

Baltimore Noir, edited by Laura Lippman

Boston Noir, edited by Dennis Lehane

Bronx Noir, edited by S.J. Rozan

Brooklyn Noir, edited by Tim McLoughlin

Brooklyn Noir 2: The Classics, edited by Tim McLoughlin

Brooklyn Noir 3: Nothing but the Truth

edited by Tim McLoughlin & Thomas Adcock

Chicago Noir, edited by Neal Pollack

D.C. Noir, edited by George Pelecanos

D.C. Noir 2: The Classics, edited by George Pelecanos

Delhi Noir (India), edited by Hirsh Sawhney

Detroit Noir, edited by E.J. Olsen & John C. Hocking

Dublin Noir (Ireland), edited by Ken Bruen

Havana Noir (Cuba), edited by Achy Obejas

Indian Country Noir, edited by Sarah Cortez & Liz Martnez

Istanbul Noir (Turkey), edited by Mustafa Ziyalan & Amy Spangler

Las Vegas Noir, edited by Jarret Keene & Todd James Pierce

London Noir (England), edited by Cathi Unsworth

Los Angeles Noir, edited by Denise Hamilton

Los Angeles Noir 2: The Classics, edited by Denise Hamilton

Manhattan Noir, edited by Lawrence Block

Manhattan Noir 2: The Classics, edited by Lawrence Block

Mexico City Noir (Mexico), edited by Paco I. Taibo II

Miami Noir, edited by Les Standiford

New Orleans Noir, edited by Julie Smith

Orange County Noir, edited by Gary Phillips

Paris Noir (France), edited by Aurlien Masson

Phoenix Noir, edited by Patrick Millikin

Portland Noir, edited by Kevin Sampsell

Queens Noir, edited by Robert Knightly

Richmond Noir, edited by edited by Andrew Blossom,

Brian Castleberry & Tom De Haven

Rome Noir (Italy), edited by Chiara Stangalino & Maxim Jakubowski

San Francisco Noir, edited by Peter Maravelis

San Francisco Noir 2: The Classics, edited by Peter Maravelis

Seattle Noir, edited by Curt Colbert

Toronto Noir (Canada), edited by Janine Armin & Nathaniel G. Moore

Trinidad Noir, Lisa Allen-Agostini & Jeanne Mason

Twin Cities Noir, edited by Julie Schaper & Steven Horwitz

Wall Street Noir, edited by Peter Spiegelman

FORTHCOMING:

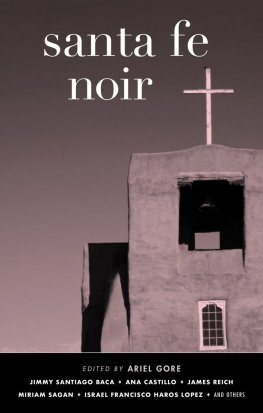

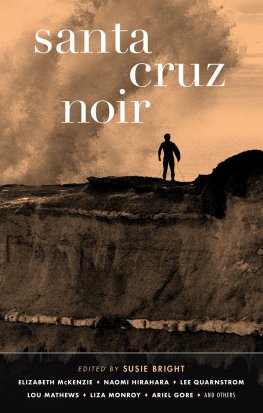

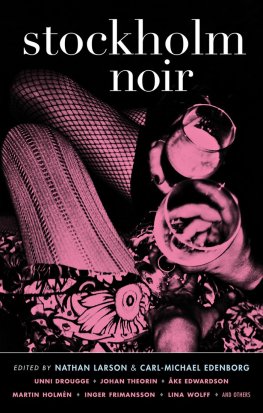

Barcelona Noir (Spain), edited by Adriana Lopez & Carmen Ospina

Cape Cod Noir, edited by David L. Ulin

Copenhagen Noir (Denmark), edited by Bo Tao Michaelis

Haiti Noir, edited by Edwidge Danticat

Lagos Noir (Nigeria), edited by Chris Abani

Lone Star Noir, edited by Bobby Byrd & John Byrd

Mumbai Noir (India), edited by Altaf Tyrewala

Philadelphia Noir, edited by Carlin Romano

CITY OF BROKEN DREAMS

Translated by Marian Schwartz

W hen we began assembling this anthology, we were dogged by the thought that Russian noir is less about the Moscow of gleaming Bentley interiors and rhinestones on long-legged blondes than it is about St. Petersburg, the empires former capital, whose noir atmosphere was so accurately reconstructed by Dostoevsky and Gogol. But the deeper we and the anthologys authors delved into Moscows soul-chilling debris, the more vividly it arose before us in all its bleak and mystical despair. Despite its stunning outward luster, Moscow is above all a city of broken dreams and corrupted utopias, and all manner of scum oozes through the gap between fantasy and reality.

The city comprises fragments of utterly incommensurate milieus, notes Grigory Revzin, one of Moscows leading journalists, in a recent column. The word incommensurability truly captures the feeling you get from Moscow. The complete lack of style, the vast expanses punctuated by buildings between which lie four-century chasmsa wooden house up against a construction of steeland all of it the result of protracted (more than 850-year) formation. Just a small settlement on the huge map of Russia in 1147, Moscow has traveled a hard path to become the monster it is now. Periods of unprecedented prosperity have alternated with years of complete oblivion.

The center of a sprawling state for nearly its entire history, Moscow has attracted diverse communities, who have come to the city in search of better livesto work, mainly, but also to beg, to glean scraps from the tables of hard-nosed merchants, to steal and rob. The concentration of capital allowed people to tear down and rebuild ad infinitum; new structures were erected literally on the foundations of the old. Before the 1917 Revolution, buildings demolished and resurrected many times over created a favorable environment for all manner of criminal and quasi-criminal elements. After the Revolution, the ideology did not simply encourage destruction but demanded it. The Bolshevik anthem has long defined the public mentality: We will raze this world of violence to its foundations, and then/We will build our new world: he who was nothing will become everything!

Back to the notion of corrupted utopias: much was destroyed, but the new world remained an illusion. Those who had nothing settled in communal apartments. After people were evicted from their private homes and comfortable apartments, dozens of families settled in these spaces, whereupon a new Soviet collective existence was created. (Professor Preobrazhensky, the hero of Mikhail Bulgakovs Heart of a Dog, happily avoided this consolidation. In the novel, set in post-revolutionary Moscow, the professor transplants a human pituitary gland into a dog in hopes of transforming the animal into a person. The half-man who results from this experiment immediately joins up with the Reds. The test is a failure. In Bulgakovs opinion, he who was nothing could not become everything.) That form of survival existed in Moscow until very recently, and from the average westerners standpoint, nothing more oppressive could ever be devised: an existence lived publicly, in all its petty details, like in prison or a hospital.

The story of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior is a fairly graphic symbol of how Moscow was built. The church was constructed in the late nineteenth century on the site of a convent, which was dismantled and then blown up in 1931, on Stalins order, for the construction of the Palace of Soviets. The Palace of Soviets was never built (whether for technical or ideological reasons is not clear), and in its place the huge open-air Moskva Pool was dug out by 1960; it existed until the 1990s, when on the same site they began resurrecting the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, symbolizing new Russia.

The more you consider the history of Moscow, the more it looks like a transformer that keeps changing its face, as if at the wave of a magic wand. Take Chistye PrudyPure Ponds (the setting for Vladimir Tuchkovs story in this volume)which is now at the center of Moscow but in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was in the outskirts and was called Foul or Dirty Ponds. The tax on bringing livestock into Moscow was much higher than the tax on importing meat, so animals were killed just outside the city, and the innards were tossed into those ponds. One can only imagine what the place was like until it finally occurred to some prince to clean out this source of stench, and voil! Henceforth the ponds were clean.

Next page