CONTENTS

FOR MY PARENTS

Oh Lord, wont you buy me a Mercedes-Benz?

JANIS JOPLIN

A MERCEDES IN OUAGADOUGOU

I dont think I ever would have thought of it myself. Visiting Ouagadougou, I mean. A good friend of mine, a fellow Dutchman, was getting married there, in the capital of the West African country Burkina Faso. To a Burkinab. And I didnt want to miss that. The wedding lasted three days and three nights. The last night, exhausted, I hailed a cab. Now, Burkina Faso is one of the worlds poorest countries, and I knew that most of the cars there are far from new. But this one had them all beat. The body was battered on every side, the headlights were missing, the tires, bald. Clouds of ink black smoke poured from the tailpipe. The interior wasnt much better: where once the odometer had been was now a gaping hole. Springs protruded through the seats. The upholstery on the doors had all but disappeared, leaving bare metal.

S tuck to the cracked dashboard was a decal of the Dutch soccer team PSV Eindhoven.

A PSV Eindhoven fan in Ouagadougou? I tapped on the teams red and white logo and asked the driver if he was an admirer of Dutch soccer.

He had no idea what I was talking about. Hed never heard of PSV, didnt give a damn about soccer. He didnt even know where the Netherlands was. And that decal had always been there. It looked it, too. Yellowed. Frayed at the edgessomeone had tried in vain to pull it off. How had that decal wound up in an African taxi? Had the previous owner, perhaps, been a PSV fan? As fascinating as the thought was, a PSV fan in Burkina Faso seemed improbable. Wasnt it more likely that an even earlier owner had been a fan of the Dutch soccer team? That had to be it: that car came from the Netherlands. And sure enough, when I got out, my suspicions were confirmed. In Europe, every car has a white oval decal on the back with one or two black letters to indicate the cars country of origin: F for France, S for Sweden, PL for Poland, and so on. This one was no different: a white decal with the letters NL was stuck to the rear end.

I t was a Mercedes 190 Diesel, that taxi in Ouagadougou.

THE PURCHASE

Year: 2004

Mileage: 136,400

Price: $1,200

Owner: Jeroen van Bergeijk

T here are ads like this on the Dutch Internet auction site marktplaats.nl all the time:

For sale: 1988 Mercedes 190 D

Price: $1,400

136,400 miles. Alarm. Black 4-door.

Excellent condition.

Recent checkup, oil change,

safety and emissions inspection.

This one gets my attention because everything about it seems right: the kind of Mercedes Im looking for, a reasonable asking price, not too many miles, and a recent inspection. My phone hasnt stopped ringing, the owner says when I call his cell phone number on a Saturday morning. You can have a look, but the first good offer gets it. I drive immediately to one of the new suburbs just outside The Hague. The owners name is Ronald. He works for the police. And so, the implication is, can be trusted. Ronald is a well-built man with close-cropped hair, about what youd expect for a police officer. Taciturn, a bit stern, but not unfriendly.

We stroll to his Mercedes, which seems rather out of place among the brand-new gleaming mid-class cars parked on Ronalds tidy little street. The finish is dull. Theres a crack in the bumper. The sunroof doesnt open anymore. The drivers seat sags, and the doors dont lock.

I couldnt get that cab in Ouagadougou out of my mind. On the plane home to Amsterdam, Id obsessed about how that car had wound up there. I imagined a Dutch aid worker whod gotten the Mercedes from his uncle and imported it through the port in neighboring Benin. Maybe an African immigrant to the Netherlands had bought the car and sent it to his family in Burkina Faso. Or some adventurous Dutchman had driven that Mercedes 190 straight through the Sahara to Ouagadougou to sell it there to the highest bidder. But what really happened? How did a Dutch car end up in Africa?

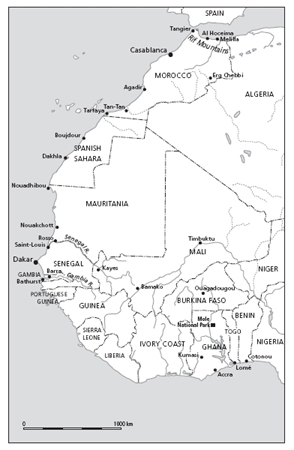

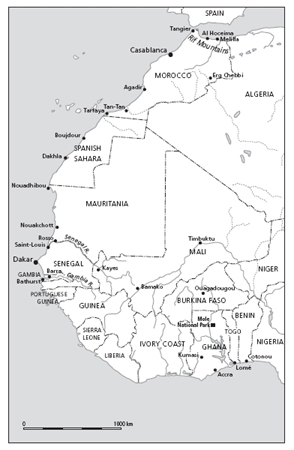

T ake Ronalds Mercedes. A seventeen-year-old car is, in fact, living on borrowed time: the average life expectancy of an automobile in Western Europe is only fifteen years. For a car like Ronalds there are really only two scenarios. Most likely itll end up on the scrap heap. Not because a seventeen-year-old car is in such bad condition but because the cost of the repairs it will soon undoubtedly need will greatly exceed the cars value. In Western European countries like the Netherlands, Ronalds car has lost its usefulness. But in countries where the cost of repairs is much lower, the same car is still worth something. Hence the other scenario for Ronalds Mercedes: export. Of the more than seven million cars driving around on Dutch roads in 2005, more than a quarter million had been exported by the end of the year. All the wealthy Western European countries export their old automobiles, millions in total. Nowadays most go to Eastern Europe, but a considerable minority, an estimated 500,000 per year, wind up in Africa. That Dutch Mercedes in Ouagadougou is not alone. The Opel Astra of a traveling salesman from Hamburg spends its days as a bush taxi in Ghana. The Toyota Corolla of a Parisian housewife is now the property of a camel trader in Mauritania.

Most of the old automobiles that leave Europe for Africa are shipped by boat, but a small number are driven there. In fact, since the 1970s, driving a used car to West Africa has become a popular pastime among French, Belgian, German, and Dutch adventurers. These people are like the godwits, terns, and swallows that summer in Europe. Every winter they flock to West Africa, selling their castoffs at a tidy profit in countries like Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. To get there, they have to bribe customs officials, befriend corrupt cops, andabove alldrive straight through the Sahara.

I go for a test drive in Ronalds Mercedes. It appears to have few mechanical problems: the engine runs well, the brakes are in order, and though the acceleration is a little sluggish, it shifts easily. It looks a bit shabby here in this brand-new suburb, but for a seventeen-year-old car its in excellent shape. Ouagadougous cabbies will envy me. I even get Ronald to knock two hundred dollars off the price, and a little later its mine, that African-taxi-to-be.

OKAY, THAT WONT WORK

A t the motocross track down by Amsterdams western docks, the whining of dirt bikes never stops. The sky is slate gray. It drizzles off and on. The track is half-covered with weeds and young willow trees. Its not the Sahara, but there is sand, and thats what counts. Im here with Ruben and Raoul, who are going to teach me how to drive an ordinary automobile through loose sand. Ruben is a mechanical engineer, and hes already driven across the Sahara four or five times. He wears oversize glasses. He knows all there is to know about cars. Raoul is the owner of Off-Road Adventures, a company that rents Land Rovers and organizes team-building events in the Ardennes region of Belgium at which participants master some of the finer points of vehicle control. Raoul has a big mop of curly hair, wears a macho leather jacket, and is a huge fan of the Rolling Stones. His dream is to one day drive in the ParisDakar desert rally. Hes been preparing for it for years. The problem is it costs an enormous amount of money; professionals easily spend a few million on it. Even if you want to do it on the cheap, you still have to plunk down a couple hundred thousand, and Raoul doesnt have that kind of dough.

Next page