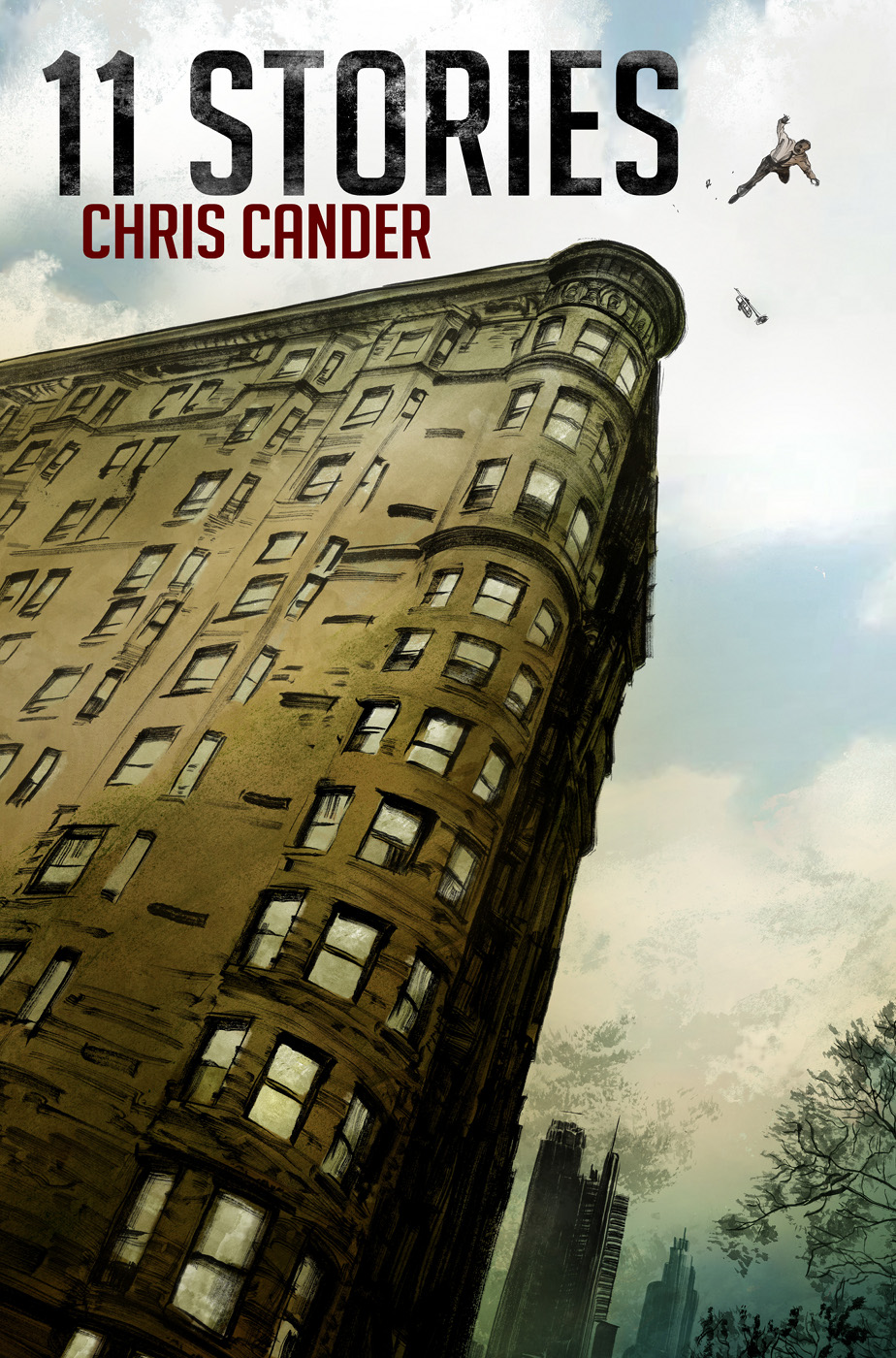

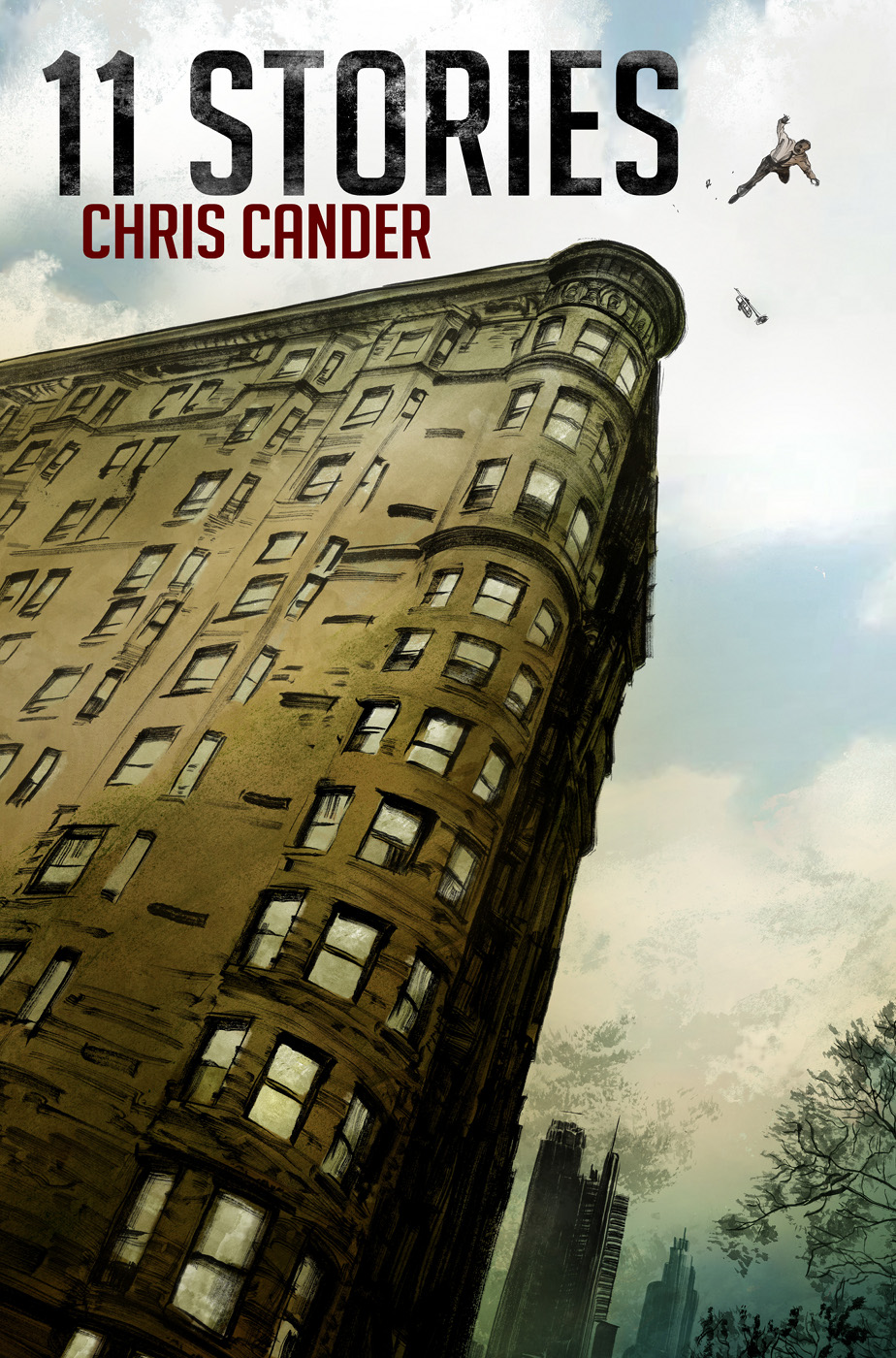

11 STORIES

CHRIS CANDER

Rubber Tree Press

Houston, Texas

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are a product of the authors imagination. Locales and public names are sometimes used for atmospheric purposes. Any resemblance to actual people, living or dead, or to businesses, companies, events, institutions, or locales is completely coincidental.

Copyright 2013 by Chris Cander.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Rubber Tree Press, Houston, Texas.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013934292

Cander, Chris, 2013

11 stories / Chris Cander

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-9889465-2-1

Smashwords Edition

Cover Illustration 2013 Greg Ruth

First Edition

QED stands for Quality, Excellence and Design. The QED seal of approval shown here verifies that this eBook has passed a rigorous quality assurance process and will render well in most eBook reading platforms.

For more information please click here.

For Charlie

YESTERDAYS

I t was a long way up for a sixty-seven-year-old man. Hed climbed those stairs nearly every day since hed learned to walk; as a child toddling behind his mother, a boy with mischief in his bones, a young man seeking solitude. Mostly, though, he had climbed them as the superintendent of the building both master and servant to the tenants who lived above him.

He used the steel-cage elevator sometimes, mostly to carry something heavy to the upper floors; a ladder, for example. His toolbox. Or if it was the end of a long day and someone buzzed for him, needing something urgently: a toilet was overflowing its unspeakable sludge, a boiler wasnt circulating, or in one residents opinion another was making too much noise.

Once, he was roused from his basement office (really just a small room that fronted his modest living quarters behind the laundry room) because a bird that turned out to be a black-crowned night heron, probably from the nature sanctuary a few blocks south, had inexplicably flown into one of the windows on the tenth floor. It didnt quite break the glass, but it unnerved the spinster whod been sitting in the seat beneath it reading the book of Revelation and smoking something that smelled a lot like marijuana. After Roscoe had taped the window and promised hed have the whole thing changed in the morning, hed had to sit down on the edge of her plastic-covered sofa until she was calm enough to allow his leave.

Afterward, hed carried a box down to the sidewalk beneath her window, wrapped the broken bird in an old towel and taken it back to his quarters. He could have incinerated it the way he did all the rest of the flotsam and jetsam the tenants deemed trash, but he felt sorry for it in that moment of darkness. So he laid the box on the floor of his living room and said a prayer he could remember his mother saying at the funerals of his uncles, one by one; his grandmother; a distant cousin; and of course, his father. We thank you for his life and his death, for the rest in God he now enjoys, for the glory we shall share evermore at your right hand, in Jesuss name. Amen. It was the first time hed ever said a prayer on his own. Even sitting in the front pew at his mothers funeral in the spring of 64, when he was only twentyjust two years after burying his father hed had no words to pray. Instead, in the nightclub of his mind, hed heard the lyrics of Chet Bakers ironic, iconic, I Get Along Without You Very Well. But thats how he was. Words came uneasily from his mouth, but not music. Music fell freely.

He was tired by the time he opened the door to the roof, but once he stepped out onto the terrace his fatigue dissipated. It was one of those unseasonably warm October evenings. The dry breeze lifted peoples spirits and windows and inspired them to spill out onto the streets, pushing baby strollers and following dogs from one hydrant to another with blithe patience or taking early dinners alfresco at any of the countless cafs with their folding chairs and tables. Irish pubs flung open their windows and the Italian grocer set up a table outside his shop with pumpkins and pomegranates. Roscoe let the door shut behind him and stood on the roof, his old Blessing Standard trumpet dangling from the loose grip of the hand that still had all five long, slender fingers. He tipped his head back, closed his eyes, and filled his lungs with the crisp, pinked, sunset air that mingled with the exhaust from the compactor room.

Several years before, some of the tenants had started a community garden. There were five rows of planter boxes, each of them six feet long and two wide, bursting with herbs and squash and other small crops. He walked past but then stopped, triggered by something, and went back to the first box. He bent down and relieved the top of one woody rosemary stem of its spikey leaves, rolled them between his fingers and held the tips to his nose. Hed always loved rosemary. The smell of it reminded him of something that seemed just out of reach, some memory or reality to which he wasnt quite entitled but yearned for all the same. He dropped the bruised leaves and continued.

The corner of the roof where the south and east faces met wasnt really a corner at all. It was round and stood out several feet beyond the main structure like a turret. He had to climb over a short wall to get out to the curved edge, but even with that minor inconvenience he never could understand why he was always alone up there. Why everyone didnt climb out and lean against the precipice to watch the sun come up over the lakes horizon or just to get a sense of perspective, to look down at things and realize how small they really were. When he was young, hed passed many hours tucked behind the cornice, its lions heads lined up beneath his own like a row of personal guards. It had been a good place to hide from his father, who knew the building almost as well as Roscoe did. His father never did discover him crouching behind that little parapet, sitting out a scolding or waiting for a mood to pass. Roscoe practiced the trumpet there, too, because he could blow into the wind and his notes would get carried away without anybody hearing, especially during those difficult years when he had to learn a new way of fingering the valves.

But this evening, with its perfect sunset and clear, dry sky, Roscoe Jones wasnt going out to hide. There was nobody to hide from; everyone that mattered was gone.

This evening, he was seeking.

He lifted first one creaky, aching leg over the small dividing wall and then the other, and walked up to the curved and sloping edge. He stood there, pressing his old-man belly against the terra cotta for a moment, gathering his strength, and then hoisted himself up onto the flat ledge, careful not to lose his footing or drop his trumpet, because that would have ruined everything.

Once his feet were under him, he stood slowly up to his full and impressive height and without closing his eyes or moving his mouth he said the second prayer of his adult life, which was actually more like a wish. Then he took a deep breath and looked out from this strange elevation at the world below and beyond. It was like being a preacher behind a pulpit, waiting for the faithful to settle down before beginning the sermon, or an actor on a thrust stage, waiting for the spotlight to illuminate the scene. He stood there holding his trumpet, and when he was ready, he brought it to his lips.

Next page