Other titles in the STRANGEST series

Crickets Strangest Matches

Footballs Strangest Matches

Golfs Strangest Rounds

Laws Strangest Cases

Londons Strangest Tales

Medicines Strangest Cases

Motor Racings Strangest Races

Rugbys Strangest Matches

Shakespeares Strangest Tales

Teachers Strangest Tales

Tenniss Strangest Matches

Titles coming soon

Cyclings Strangest Tales

Fishings Strangest Tales

Horse Racings Strangest Tales

Sailings Strangest Tales

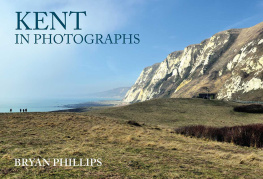

Extraordinary but true stories from a very curious county

MARTIN LATHAM

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I think I enjoyed wonders too much to write a good PhD. As my excellent supervisor Peter Marshall said, I kept wandering off into chatty stories. In this book I can indulge my passion for history as told by tales. I hope Professor Marshall will put a copy in his lavatory. Indeed, the smallest room is a good place for this book in any home, as there are tales to suit any length of stay.

I am a Londoner who, in 20 years of Canterbury bookselling, has fallen in love with Kents wonders. I hope you enjoy dipping into this book, as I have loved writing it. The interwar poet Richard Church said that, while writing his book on Kent, he developed a mystical relationship with the place. I might not claim that, but it has become, for me, as enchanted as Samarkand.

What a county! Nightingales haunt ancient woods, the marsh birds are internationally important, otters breed, seals bask in secret coastal nooks, and peregrine falcons speed through the air. The garden of England sounds so cosy, but the garden has been dotted with chairs from which writers blew our minds: Darwin and Dickens, H.G. Wells, Joseph Conrad and T.S. Eliot all wrote their masterpieces here. Its sinuous flints stirred Henry Moore to sculpt a new humanity, and its glorious storms helped inspire Van Gogh and Turner to transform painting. Turner once said that the light over East Kent beat anything in Italy.

This county of Kent, lying between London and Europe, can never be dull or parochial. Caesar fought woad-painted tribesmen here, and marauding Vikings felled an Archbishop of Canterbury with an ox bone. In medieval times, the port of Romney survived on importing wine and garlic. Along Kents northern shore, Pocahontas died, Nelsons ships were built and Sir John Franklin set sail on his doomed expedition to discover the Northwest Passage. To the east, German destroyers shelled Broadstairs in the Great War, and the Luftwaffe pounded the whole county in the Second World War. Incoming trucks at Dover hide illegal immigrants from as far away as Afghanistan, and the county has its own vigorous criminal class. Kent invented chavs; they come from Chatham.

I have included myths, nature and some paranormal tales, because they too are Kents story. As Coleridge pointed out when lamenting that Wordsworth did not believe in fairies, we cannot live only on matter-of-factness.

Most of all, I hope you enjoy discovering the more obscure individuals as much as I have loved unearthing them. I do not believe that any novelist would dare to portray the bounders, narcissists, losers, fantasists, nutters and quiet heroes who abound in these pages. So, to quote Evelyn Waughs preface to Eric Newbys A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush: Dear Reader, if you have any softness left for the idiosyncrasies of our rough island race, fall to and enjoy this.

Thanks to two kind and inspiring friends: Professor Peter Marshall, who taught me to research, and the late Dr Katherine Wyndham, who inspired me to write history and climbed trees with me. The quality of my knowledge has been much improved by many conversations with Dr Paul Bennett, Director of the Canterbury Archaeological Trust, and with his predecessor, Tim Tatton-Brown. The County Archaeologist, John Williams, urbanely answered queries. The late scholar Simon St Clair Terry understood Kent better than anyone I have met, and he gave of his erudition freely, and often hilariously. Likewise, the late Alan Clark inspired my history-writing by verbal encouragement, and I regret that I never took up his offer to write the history of Saltwood Castle. Sissinghurst features rather largely in the book, because the late Nigel Nicolson repeatedly agreed to my requests to give talks in my bookshop about the house, and about his parents Vita and Harold. I must thank Tim Waterstone for giving me the best workplace I can imagine, and asking me to make it an Aladdins cave of books.

The Keeper of Prehistoric Antiquities at the British Museum answered many queries and John Badmin, doyen of the Kent Field Club, kindly told me about Kents natural wonders. Folkestone Tourist Office helped me to track Samuel Becketts movements in the town, and Deals inimitable Town Clerk, Linda Dykes, helped with Turner in Kent.

At my publishers previously Anova, now Pavilion Pollys faith in me was very heartening, while Malcolm Croft was a gentle polymath with a rapier wit. My thanks to Katie Cowan and Nicola Newman for the opportunity to collaborate on a new edition, and to Victoria Nairn and Katie Hewett for bringing it to fruition. Thank you to my children: Ailsa for a wise and listening ear, Oliver for keeping the tales readable (and supplying two), India for enthusiasm when I doubted, Caspar for being Horatio when I was a dithering Hamlet, and William for verbal virtuosity. My stepchildren have endured my rambling anecdotes; Francesca, Jack and Sam thanks. My wife Claire is a fantastic editor who saved the reader from many verbal infelicities, and secured my felicity throughout.

Martin Latham

. Coleridge is quoted in Duncan Wu, William Hazlitt, the First Modern Man (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Kent ... sweet is the country, because full of riches

(William Skakespeare, Henry VI,

Part II, Act IV, Scene VII )

BRITAINS OLDEST HIGHWAY?

600,000 BC

The North Downs, as you can see by looking across the Channel, are mirrored by chalk cliffs in the Pas de Calais. The English Channel was created about 400,000 years ago. Before that, there was a land bridge to the continent, from Calais to Dover. Bipedal hominids, as archaeologists romantically call the early prototypes of mankind, originated in Africas Rift Valley and spread to Europe over a million years ago. Their entry route into England was along the CalaisDover chalk ridge, continuing inland along the North Downs.

Kent was Early Mans bridgehead into Britain. Our primitive ancestors crossed the chalk land bridge to Dover and fanned out. Evidently, many colonists remained in Kent, for one archaeologist has called it the richest county in England for evidence of prehistoric man. So far, an exceptional 40,000 artefacts have been found from this ancient influx.

Ornithologists still report that this remains an ancient avian highway, a route used by many migratory birds into England. They are following our early ancestors. This intercontinental highway has continued in use by birds and man for millennia.

Next page