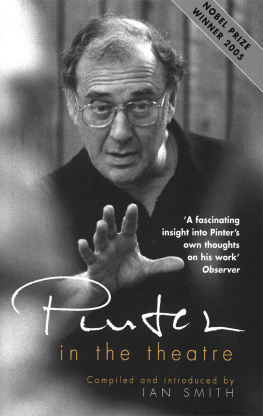

Pinter in the Theatre

Compiled and introduced by

Ian Smith

Foreword by

Harold Pinter

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Foreword

Ian Smith plays cricket for Gaieties CC. He makes big 100s and his batting average last season was 71. I therefore had every confidence in him when it was proposed that he edit this book. His chosen team certainly play shots all round the wicket.

Ive worked in the theatre for over fifty years as writer, director and actor. (I even designed a play of mine once Ashes to Ashes in Italian in Palermo. I called the designer Gomez.) Actors and directors have therefore been a constant factor in my life. A number of them are dead and some are on the wagon but the ones in this book are certainly alive and kicking. It was a great pleasure for me to work with all of them.

I would not exactly describe any of them as shy, but I have never heard them speak so openly and fully as they do here. Ive probably learnt a great deal from their candid and fearless accounts.

HAROLD PINTER

Introduction

First, a few words from Pinter himself:

He is his own man. Hes gone his own way from the word go. He follows his nose. Its a pretty sharp one. Nobody pushes him around. He writes what he likes not what others might like him to write.

But in doing so he has succeeded in writing serious plays which are also immensely popular. You can count on the fingers of one hand those who have brought that off. But, indisputably, hes one of them.

This was written by Pinter for the fiftieth birthday of his friend Tom Stoppard, but all of it, with the possible exception of the last sentence, applies equally well to Pinter himself.

Through interviews with Pinter and important collaborators, this book expands on some of Pinters remarks. It examines how he has gone his own way from the word go. It examines the serious nature of his work, and how it is embedded in the intellectual and political context in which he has spent his life. And it considers something that is occasionally taken for granted in Pinter criticism; that Pinters work, for audiences wherever it has been played, has always been immensely popular.

All the new interviews for this book focus on the process of making Pinters plays work in performance, as compelling depictions of human action. In a Pinter drama, an action or motive may on occasion be unexpected or even inexplicable, but the mystery is intriguing only to the extent that the character or the relationship involved is credible and interesting. This living theatrical life of the characters, and through them of the plays, is a prerequisite for the intellectual depth of the plays, not an addition or complement to it. As Pinter has said, if a living performance does not take place, intellectual resonance cannot exist.

This introduction deals mainly with Pinters background, education, and early years in the theatre. A detailed account of his entire career, or of critical debates around his work, would be impossible in the space available, and in any case the formative years are of special importance for any writer. This focus is especially justified here because of Pinters remarkable emergence, around his thirtieth birthday, with a striking, innovative and entirely coherent style that offered distinctive challenges, as well as great rewards, to players and audiences. That style has seen many developments and experiments over more than forty years. But definitive artistic and intellectual elements of Pinters work have been present from the start. In this book, the introduction examines the origins of this style, and the actors and directors describe how it is put into practice. The interviews offer comment on Pinters training in the theatre, and on the mechanics of rehearsing and performing his work.

Two very significant critical points emerge from the study of Pinters background and intellectual development: first, that his writing and thought have always been inseparable from political concerns that were omnipresent in his early life; second, that from a precociously early age Pinter has been a committed and self-conscious intellectual not merely a person of what the British call highbrow taste, but one who scrutinises and mediates his experience through a body of knowledge and a critical apparatus acquired and developed through learning and debate. To argue, as some do, that in his intellectualism Pinter is not being true to his roots is to reveal ignorance both of him and of the rich cultural life of the communities in which he grew up and then studied and worked in his early years (if anything, it is in the more privileged and wealthy circles in which he now sometimes moves that Pinters intellectualism and seriousness appear most often to create unease).

Pinters achievement is the product of a complex individual sensibility and immense talent, but also of his background and early years: the family circumstances, the intellectual and political influences, and a decade of furious work in the theatre, which combined to form him as a writer.

*

Tell me more, with all the authority and brilliance you can muster, about the socio-politico-economic structure of the environment in which you attained to the age of reason.

Spooner to Hirst in No Mans Land, Act I

Pinter was born on 10 October 1930, in Hackney, East London. His father and mother were children of Jewish immigrants whose families hailed from Central or Eastern Europe. Three of his grandparents were from Odessa. His father, Jack, worked as a jobbing tailor and as a cutter: in bespoke tailoring it is the cutter, not the proprietor of a shop who is the better craftsman, shaping cloth to create style and flatter individual physiques. According to one actor who met him, Jack Pinter was also a champion Charleston dancer in the 1920s (Pinter has told me that in the early 1960s he enjoyed dancing to jazz). Pinters mother and other members of the family were interested in the arts, especially music.

He did not have a religious upbringing, and, though issues of the human spirit and the uncanny have intrigued him in recent years, he says that the last religious ceremony he attended, apart from weddings and funerals, was his bar mitzvah at the age of thirteen. Nevertheless, Pinter believes that Jewishness has been significant in shaping his personality and his writing. More than perhaps any other prominent British writer of his time, he has drawn on and developed twentieth-century aesthetic traditions that were forged in Europe in conditions of upheaval, deracination and alienation of many kinds. It has often been noted that most of the literary canon of Modernism was written by exiles and emigrs, many of whom were working in a language or idiom that was not their first, subjecting even the most commonplace words and phrases to an intense and productive scrutiny. Pinters Jewish-immigrant background placed him squarely in this tradition. None of his four grandparents spoke English as a first language.

The claustrophobic and intense domestic relations of many of the plays seem to Pinters old friends, among others, another part of his Yiddishkeit (the term used in conversation with me by his lifelong friend Henry Woolf). Warren Mitchell, an actor of similar age and background to Pinter, grew convinced while rehearsing the role of Max in The Homecoming, that the character should be played as a Jewish patriarch, though he said that when he put this to Pinter, he was only In the memories of Pinter and his friends, Jewishness reinforced the twin senses of vocation and alienation in young men striving to embark on artistic and intellectual careers from a working-class culture in which books were an expensive, and perhaps even subversive, luxury.

Next page