RECIPES FOR RESPECT

SOUTHERN FOODWAYS ALLIANCE

STUDIES IN CULTURE, PEOPLE, AND PLACE

The series explores key themes and tensions in food studiesincluding race, class, gender, power, and the environmenton a macroscale and also through the microstories of men and women who grow, prepare, and serve food. It presents a variety of voices, from scholars to journalists to writers of creative nonfiction.

SERIES EDITOR

John T. Edge

SERIES ADVISORY BOARD

Brett Anderson | New Orleans Times-Picayune

Elizabeth Engelhardt | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Psyche Williams-Forson | University of Maryland at College Park

RECIPES FOR RESPECT

African American Meals and Meaning

RAFIA ZAFAR

for Bill, who cooks

2019 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Set in 10.25/13.5 Minion Pro Regular by

Graphic Composition, Inc.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed digitally

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zafar, Rafia, author.

Title: Recipes for respect : African American meals and meaning / Rafia Zafar.

Description: Athens, Georgia : University of Georgia Press, [2019] | Series: Southern Foodways Alliance studies in culture, people, and place Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018042681 | ISBN 9780820353661 (hardcover: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780820353678 (paperback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780820353654 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansFood. | Food habitsUnited States. | African American cooking.

Classification: LCC E185.89.F66 Z34 2019 | DDC 641.59/296073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004213

Contents

RECIPES FOR RESPECT

INTRODUCTION

Food as a Field of (Black) Action

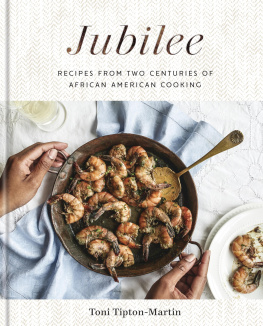

Few chefs of African descent work at the pinnacle of our national haute cuisine today, yet their contributions to American kitchens and dining rooms have been definitive. Without their expertise, the nations gastronomical heritage would be much the poorer. Bygone compendia such as Charleston Receipts, with its quaint illustrations of Geechee cooks, and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Cross Creek Cookerys sidelong nods to longtime cook Idella Parker once ruled American cookbook shelves. Such depictions of Black cooks, even if meant to be laudatory, simultaneously romanticized and be littled their efforts: their genius was untaught, their command of ingredients and techniques a priori. White employers served as the medium through which Black achievements could be made legible. Although recognition of African American culinary contributions is at long last arriving, Black cooks and hospitality entrepreneurs have been publishing recipe books and housekeeping guides since the 1820s.

I begin Recipes for Respect with anthropologist Mary Douglass keen observation that food is a field of social actionan acknowledgment that societies share nourishment with some groups and withhold access from others.

Around 1930 the bibliophile Arturo Schomburg realized that recovering the gastronomy of the African diaspora would necessitate the navigation of a vast and irresistible subject. Could he limn the lives and works of the countless anonymous cooksthe black and unknown bards of Americas kitchens? Unlike Schomburgs proposed volume, this book analyzes representative authors and texts, including Schomburgs own manuscript, rather than attempting an encyclopedic study. My book does not intend to diversify the bastions of fine dining, remake best cookbook lists, or recalibrate the minds of food columnists; my meditations are not meant to stand in for a detailed history of African Americans in the kitchen. Rather, Recipes for Respect contemplates cookbooks, hotelkeepers guides, novels, and memoirs as revelatory venues for Black authors deployment of foodways to elevate their social status, attain civil rights, and present a dignified professional self to the public. The efforts of these authorssome primarily cooks and others primarily writersprovide a powerful counterpoint to the prevailing narrative that consigned Black Americans to a visible yet low status in the country they provisioned, fed, and served.

In discerning the connections present throughout a century and a half of Black foodways and authorship, three overlapping strategies making up a veritable Venn diagram of African American cookbooks stand out for their repeated appearances. These shared concerns or tactics can be discerned in three areas: by genre, in the creation of a Black culinary history, and through the settings where cooking and eating intersect to catalyze movements for social justice. Cookbooks, generally viewed as straightforward instruction, can do double duty as memoirs and autobiographies, etiquette manuals, epistolary narratives, and even agricultural bulletins. Cookbooks provide more than the steps needed to arrive at edible meals. Collections of recipes represent experiments in genre that forward African American social mobility and respect. Thus, we see Edna Lewis writing elegy along with her recipes, Malinda Russell looking to slave narratives when introducing her cookbook, Robert Roberts offering up an etiquette manual along with instructions for other kinds of polishing, and Tunis Campbell choreographing dining room service. Meals perform work beyond satisfying hunger, and so George Washington Carver offers suggestions for plating a dish and composting a field while the Darden sisters teach us that there is more to African American cuisine than pork and greens.

The creation of a Black gastronomy, per se, may not have been foremost on the minds of most of the authors we will encounter, although each of these works help build up that history. The past was very much on the minds of men such as Schomburg, whose collection of books and ephemera formed the basis for the New York Public Librarys vast collection of works on the African diaspora, and George Washington Carver, a scientist who cooked, and who understood the trajectory of small-scale agriculture; and women such as Edna Lewis and the Darden sisters, whose family-centered cookbooks told the tale of the Great Migration, its prequel, and its future motion. These writers may not have explicitly addressed the historical encounters of African-descended peoples with food, yet all spoke to that legacy.

That legacy of migration can legitimately be seen as southern. With few exceptions the South provides the foundation of much of what the authors in this study proposed and realized. To write of the slave narrative means to write of the South; to write of plantation recipes relies on an understanding of the regions histories; to be Black and American, in the years before immigration from the Caribbean and Africa began to rise, meant that almost certainly ones people were at some point southern-born. When author and chef Edna Lewis wrote in a posthumous essay What Is Southern? she invoked blackberry cobbler and the novelist Reynolds Price, hoppin John and Martin Luther King Jr. as emblematic of the South.

If culinary history and literary form represent the first of two ways in which food works as a field of social action, Black American writing about meals enables civil rights activism. Cookery allows authors to draw attention to the linked domains of social justice, economic mobility, and food security. Without the successful implementation of the first, the others will not follow. Discussions of eating and dining provide windows into contests over equality. Anne Moodys memoir, for example, explicitly lays out the terms of these engagements, while the Darden sisters speak to the meaning of accessible meals. The conjunction of food and writing addresses social injustice, economic pathways, the role of cooking and the kitchen in the formation of American culture, and, not incidentally, how to make a delicious meal. The following seven chapters highlight aspects of food as a field of action; collectively they provide an alternative, gustatory history of African America.

Next page