Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

TO MOM, WHO TAUGHT ME TO READ, AND DAD, WHO TAUGHT ME TO SPEAK

DECIPHERING IS THE CORRECT TERM BUT WE INVARIABLY SPOKE OF DECODING.

HUGH ALEXANDER

A CODE IS a substitution: replacing one word, letter, number, or symbol with a different word, letter, number, or symbol in order to hide the originals meaning. When spies give each other secret names to hide their true identities, this is a code. A cipher, on the other hand, is a more complex equation of variables and manipulations. This would be like when you and a friend decide to write a note to each other and agree to change all your as to bs, bs to cs, cs to ds and so on, so that none of the words make sense to anyone but you two.

Most of this story is about ciphers and the ways in which the ciphers were broken, or deciphered. Yet, as Hugh Alexander said above, we often slip from the correct to the common.

The terms code and cipher, decode and decipher, as well as codebreaker, cryptologist, cryptographer, and cryptanalyst are used interchangeably throughout this story.

1929Warsaw, Poland

THE BOX ARRIVED on the last Saturday in January.

Business in the Polish customs office went on as usual, the rhythm of sorting and inspecting undisturbed by the heavy package with a German postmark. In fact, the officer in charge had nearly finished when the urgent request came in.

Return it immediately, the German embassy demanded. There had been a mistake. It was a German package, intended for a German recipient. It should never have been sent to Poland. Cease operations and give it back.

Now, that made the customs officer pause.

He did not return the box. He opened it.

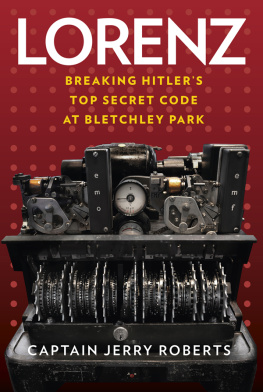

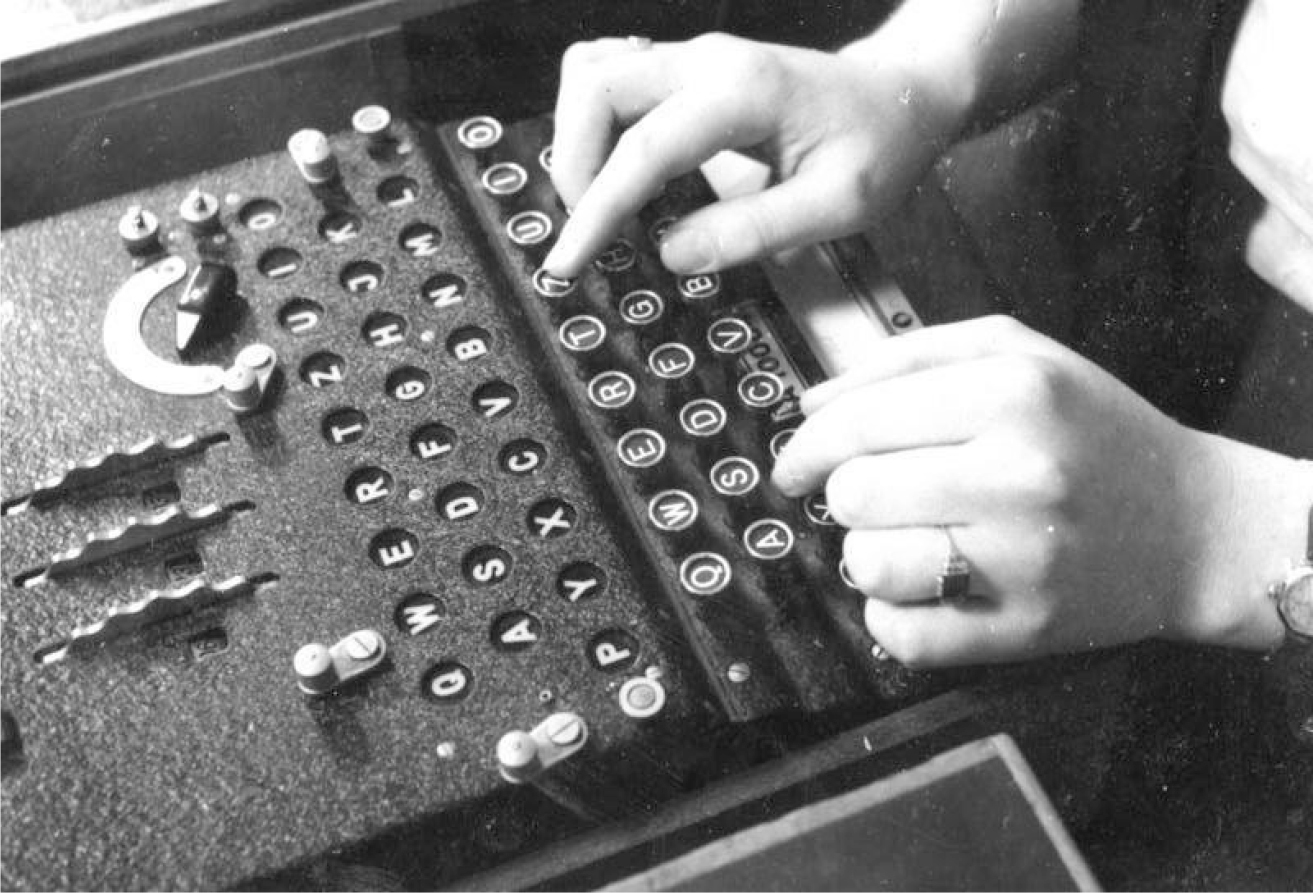

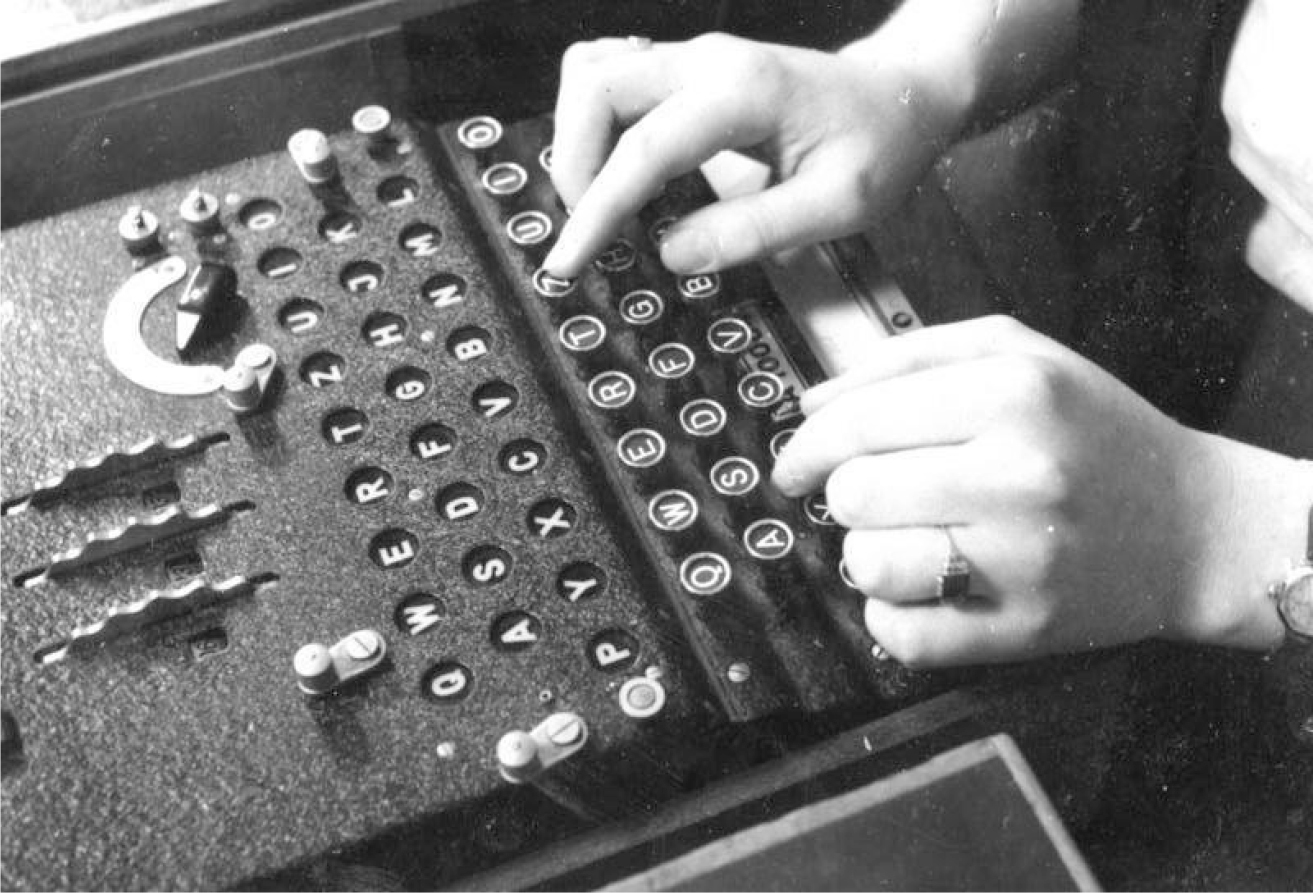

A polished surface gleamed in the light. Along a hinge in the back, a wood cover opened to reveal something almost like a typewriter. Elevated keys were arranged in three rows along the bottom, each labeled with a letter of the German alphabet.

But that was where the similarity to a typewriter ended.

There was no inked ribbon, no carriage in which to hold paper to type a letter. Instead, the top of the box was filled with small circular windows arranged in three rows identical to the keyboard below; each window contained a single letter printed on translucent material.

If the customs officer pressed a key, instantly, in the top rows, one letter began to glow. As soon as he released the key, the light went out. If he pressed the same letter key again, an entirely different light and letter shone back.

Quickly, the Polish customs officer made a call. Across town, two men secretly working for the Polish cipher agency understood immediately and rushed to the customs office.

Over the next two days and through the next two nights, the men disassembled, examined, and reassembled the machine.

By Monday morning, they had meticulously put every part back into place. They repackaged the machine in the same box and wrapped it in the same brown paper in which it had arrived.

Poland would return German property to Germany, as requested. The delay, inevitable, due simply to the weekend.

No one in Germany suspected a thing.

Enigma in use.

[Bundesarchiv, Bild 18320070705502 / Walther / CC-BY-SA 3.0]

Two years later, Sunday, November 1, 1931the German-Belgian border

Hans-Thilo Schmidt rushed through the doors of the Grand Hotel in Verviers, Belgium, two hours late. He never saw the man sitting in the lobby waiting for him.

To this man, Schmidt was an ordinary German of average build, wearing a dark hat and dark coat. Schmidt was red in the face and puffy around the eyes, both traits the man watching him had been expecting. He knew that Schmidts train was late, and Schmidt sweated and grew flushed as he hurried to make up lost time. Schmidts puffy eyes had been expected as well. The people this man watched often suffered from sleepless nights. Treason was never an easy decision.

Not that Schmidt would have noticed the man even if hed been relaxed and alert. Hans-Thilo Schmidt was far from experienced in spy craft. Last June, when he had first decided to trade secrets for money, he simply walked into the French embassy in Berlin. Incredibly, he plainly announced his intent to sell information to the French government. Without cover and without any personal security, he asked whom he should contact in Paris to do so. Somehow, he had neither been arrested by the Germans nor ignored by the French.

Now, five months later, the German Schmidt was about to meet face-to-face with a French intelligence officer. Hans-Thilo was nervous, and he was late.

At the front desk, the receptionist checked Schmidt into a room already reserved for him and handed him an envelope along with his key. He entered the elevator, and as the doors closed in front of him, the man watching him from the lobby saw him rip into the letter, which read You are expected in suite 31, first floor, at 12 noon.

At precisely noon, as the letter instructed, Schmidt knocked at suite 31.

The door opened into another world where time seemed to slow as an older woman with elegantly styled white hair greeted him and asked him to wait in the comfortable, richly furnished room. Soft music played gently over the radio. An inviting arrangement of liquor and crystal glasses was set out next to a display of fine cigars. Gratefully, Schmidt eased himself into a plush chair.

Guten Morgen, Herr Schmidt! Hatten sie eine gute Reise?

Schmidt jumped as an unfamiliar voice boomed at him in German. An immense man with a shaved head came through a doorway, entering the living area through another room in the suite. Round, dark spectacles framed icy blue eyes that pierced Schmidt with an unwavering stare.

Sit down, please, the man continued. How are Madame Schmidt and your two children?

Schmidt, already on edge, tensed more. He was currently living alone, and his wife, son, and daughter were living with his wifes parents.

I know, the man said, cutting Schmidt off before he had a chance to answer. You will want to bring your family back together soon and resume a pleasant life. That, of course, depends on you. We will assist you if your cooperation proves fruitful to us.

Taking an offered glass of whiskey, Schmidt sat back down.

The man confronting him became even more serious. Your resourcefulness last June in Berlin was quite exceptional and effective, Mr. Schmidt. Quite fortunately you happened upon an official of the French embassy who was inconspicuous. What would you have done if he had thought you were an agent provocateur and called the police?