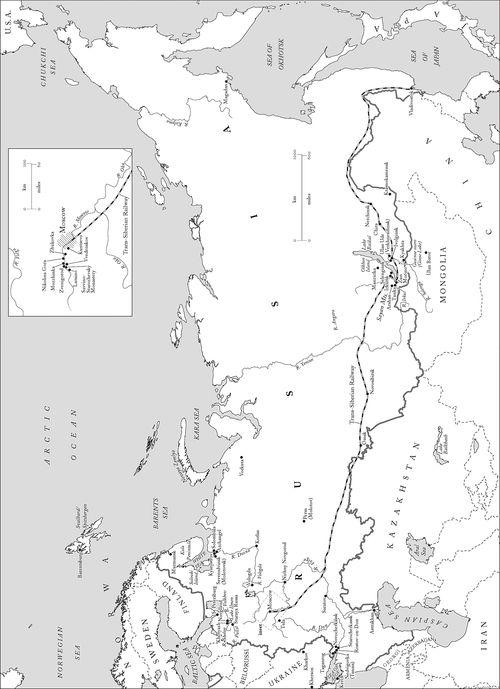

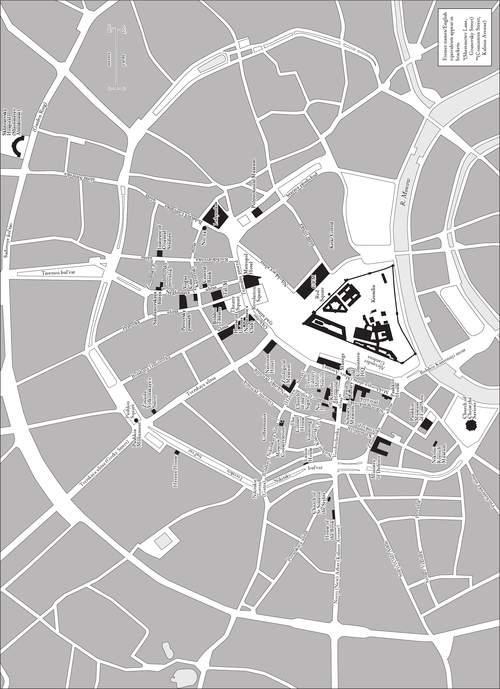

Map of Moscow showing some of the places referred to in the book

Prologue

In one corner of Molotovs drawing room stands a magic lantern.

With my back to the window that looks out over Romanov Lane, I wind the brass handle of the lantern, squinting down into the waist-high mahogany obelisk through a glass aperture as faint pictures click past on the revolving slide-carrier. A family group, ladies in old-fashioned bathing suits, smiles across from a rock on the Crimean seashore, hands shading eyes from the sun, then slips into the dark to make way for a staring shaman in torn trousers and a crooked hat; a circle of peasant women creaks past in a ritual dance, turning into three touched-up views of wooden houses and elegant public squares in the Siberian city of Irkutsk.

Have at it, the banker had said in his charming smoky drawl, dangling from one finger the keys to his apartment. He had rung our doorbell early as he passed on his way down the stairs. Youre the scholar, youll know what to make of it all.

We had met the evening before at his welcome-to-Moscow party in one of the other Romanov apartments. Over my champagne and his Jack Daniels, I told him, in my fumbling way, that I was some kind of fugitive academic, not really a journalist, working on a novel He insisted, as certain investment bankers like to do, that he was not an evil capitalist and that he loved books. His true calling was politics, he said; for over a decade he had worked quixotically for the Democratic Party in his home state of Texas.

Our conversation picked up animation when he told me about Molotovs library. I already knew that the apartment he had moved into (immediately above our own) had been the Moscow home, in the last years of his long life, of Stalins most loyal surviving henchman. I did not know that some of Molotovs possessions had remained in place left there by the granddaughter who now let the apartment to international financiers including hundreds of books, some inscribed to him or annotated in his hand, now apparently forgotten, in the lower shelves of closed bookcases in a back corridor.

My new friend the banker cannot have known what a gift he was making when he handed me those keys. In the first moments of my solitude in the grandeur of the Molotov apartment, with its spread of panelled rooms and its high stuccoed ceilings, I sensed that I had reached a destination. It was one of the destinations, even now obscure to me, for which I had made a sudden rush in that restless Cambridge spring, when the yearning to move had formed itself into a plan to come to Moscow. But a destination is rarely what we expect it to be, and destiny has a way of mocking our desires. That is one of the odd pleasures of thinking about history, including ones own, whether one believes it to be moved by chance, or providence, or the secret cunning of the dialectic.

How was I to regard Vyacheslav Molotovs abandoned library? I had not come to Moscow to pore over books like this. I was raised to value books, but these decaying volumes were residues of a malign force, not yet expired. For decades, their owner had been the second most powerful man in Stalins empire, head of his government machine and his closest and most trusted comrade, a man who collaborated diligently in the tyrants crimes, condemning millions to cruel deaths. As I lifted the books out of the shelves in soft crumbling piles, I found myself remembering a book that I had read in my teens, a gift from my father, called Nightingale Fever . It was a study by the Oxford scholar Ronald Hingley of the lives and works of four Russian poets Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva and Boris Pasternak nightingales who would not stop singing, each persecuted, in ways that were brutal and exquisite, by the Soviet state that Molotov had been so active in building and sustaining in power. I was stirred then by the way in which, in Russia, the power of poetry is confirmed by politics, by the reactions to these four poets of the men in the Kremlin who thought they could command history. But those men were no more than shadow monsters in the story of the poets my father gave me.

I read their verse, seeing little through the veil of my meagre Russian, but compelled by sounds and rhythms, and the intimation of what Mandelstam called the monstrously condensed reality which the modest exterior of lyric art contains. Some lines stayed in my head, like the first couplet of one of the poems in Mandelstams first collection, Stone :

A body has been given to me, what am I to do with it?

So single and so my own?

I could only read that poem of 1909 at once so simple and so sophisticated through the knowledge of Mandelstams death in a Gulag transit camp three decades later. For the quiet joy of breathing and living, whom, tell me, should I thank? the poet asked:

I am both the gardener and the flower,

in the dungeon of the world I am not solitary .

History is sly, and shapes strange reciprocities. If Molotov did not exist, Stalin remarked, it would be necessary to invent him. The nightingale poets, whose songs the Party could not silence, owed their tragic greatness to killers like Molotov. Mandelstams widow Nadezhda says in her memoir Hope against Hope that the image of thin-necked bosses in the short poem that Mandelstam wrote about Stalins tyranny (the poem that led to his first arrest in 1934) was inspired by the sight of Molotovs thin neck sticking out of his collar and the small head that crowned it. Just like a tomcat, Mandelstam said, pointing at a portrait of Molotov. In the course of things, Molotov even did Mandelstam a kindness. It was he who personally arranged a trip to the southern republic of Armenia for Mandelstam in the late 1920s (when his poetic gift had been dry for years), giving instructions to local Party organisations that the poet and his wife should be looked after properly. Armenia restored the gift of poetry to Mandelstam, his widow Nadezhda remembered, and a new period of his life began.

*

A look back at the past is a magic-lantern show. Memory is structured so that, like a projector, it illuminates discrete moments, Akhmatova said, leaving unconquerable darkness all around. I have a small set of images ready to be summoned at will to my minds eye that illuminate moments on my way to the Molotov apartment.

I remember the gold letters on the spine of a black book on the shelves in my fathers study Nicolas Berdyaev, The Meaning of History beneath which I slept on a camp bed for a few weeks in my childhood. I did not open the book (in which, as I later dis covered, my grandfather had pencilled his name in Adelaide, South Australia, in the year 1937) but the assertion on its spine history has a meaning took root in my mind, conjoined with a Russian name.