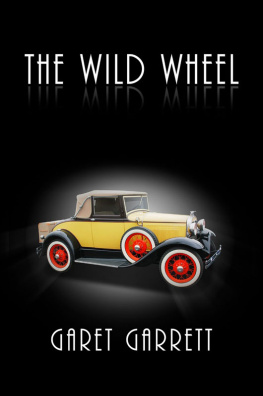

THE WILD WHEEL

Garet Garrett

PANTHEON BOOKS, NEW YORK

Copyright 1952 by Pantheon Books Inc.

333 Sixth Avenue, New York 14, N. Y.

First Printing

February, 1952

The author and publishers express herewith their thanks to the Free Library, Philadelphia (Automotive Collection), the Ford Motor Company, Dearborn and New York, and Wide World Photos Inc., New York, for kind permission to reproduce photographs from their collections.

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES BY KINGSPORT PRESS, INC., KINGSPORT, TENNESSEE DESIGNED BY ANDOR BRAUN

CONTENTS

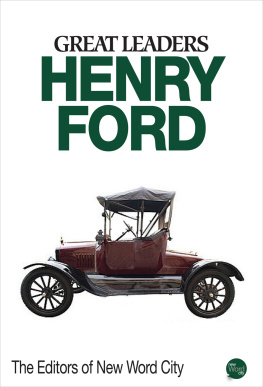

FOREWORD

L AISSEZ FAIRE was a religion that grew to full size in the American environment and never anywhere else. It was founded on the doctrine of Adam Smiths unseen hand, the mysterious power of which was to bring it to pass that the individual, freely pursuing his own selfish ends, was nevertheless bound to serve the common good, whether he consciously intended to do so or not, or ever thought about it at all. It was cruel in the way that nature is cruel to weak and marginal things; but it worked. How and why naturally it produced here the most fabulous material achievement in the history of the human race is the subject of many heavy and quarrelsome books in the library of social and economic theory. The idea of this book is to make you see it working through the eyes of its darling practician.

If in this country, for both good and evil, free private enterprise had its logical manifestations in a prodigious manner, so Henry Ford was its extreme and last pure event. After him it was different. The religion declined. It no longer exists in the orthodox form anywhere.

But this is not a history of Ford and his times, nor a biography either, furnished with notes, conclusions and a philosophy of meaning. Rather, it is a structure of episode, word and deed, like a dwelling, and the man is therea kind of divine mechanic, the ultimate child of his era, acting upon his world with ruthless and terrible energy, by instinct and intuition, who thought with his hands. As you watch him coming in and going out you may not understand him. Indeed, it is very probable that he did not understand himself. But you will perhaps get some feeling of life and its lusty transactions under the creed of Laissez Faire, and thereby arrive at a judgment of your own concerning what we have left behind.

G. G.

ONE

SWEAT IN PARADISE

I T WAS Sunday. We were making up the forms of The Annalist in the composing room of the New York Times when Mr. Ochs appeared, threading his way toward us between the turtles. His arms were held a little out, as if he were bearing a load on his chest, and his eyes were wide and staring. By these signs we knew his mind was buzzing. When he spoke it was hardly above a whisper, saying:

Hes crazy, isnt he? Dont you think he has gone crazy?

We knew what he meant. The news was in the morning paper that the Ford Motor Company had announced a minimum wage of five dollars a day for all employees down to the floor sweepers; the days work at the same time was cut from nine to eight hours.

The year was 1914. Only those then living at an age of awareness can believe what a sensation that announcement made, not here only but all over the world. Until then the Ford Motor Company had been paying the prevailing wage, which was a little over two dollars a day.

American industry was rocked to its heels. Four kinds of ruin were commonly prophesied. First, Detroit would be ruined by an exodus of employers; second, those who remained and tried to meet the Ford wage scale would go bankrupt; third, the Ford Motor Company itself would fall; fourth, the Ford employees would be demoralized by this sudden affluence; they wouldnt know how to spend the money.

I said to Mr. Ochs: It might be well to have a look. Ill go out and see.

The barber who shaved me the next morning at the Book-Cadillac in Detroit said: Our Mr. Ford has gone crazy. Did you know?

At breakfast four men came to my table to confirm the barbers opinion. They were employers of labor. I asked them if they were going to leave Detroit, and they said they were. Ford could have it.

Meanwhile an event of inverted cruelty was building itself on the Ford hiring lot. When the thing happened, the bitter people of Detroit made the most of it. In near-zero weather, from before dawn until dark, thousands of wistful men were milling about in front of the employment office, which of course was swamped. They came from everywhere. It was tidal migration, rising in the hills and valleys and in other cities, like a gold rushfrom the two-dollar day to the five-dollar day. Word went forth that only a few more workers were needed and these would be found in Detroit. That had no effect at all. Every incoming freight train brought more of them, shivering in empty freight cars or clinging to the bumpers, with the light of a five-dollar job in their eyes. No matter how it got there, a motley of ten thousand disappointed and wretched men, standing on the cold side of the door to a wage earners heaven, would become restive and a little ugly. It obstructed traffic and refused to disperse. Then the police were called in; and what was perhaps the most innocent mob that had ever assembled itself anywhere was scattered by icy streams from the fire hose.

The plant was then at Highland Park. River Rouge came later.

I spent the next two days with Ford. He made it seem quite simple. He said: If the floor sweepers heart is in his job he can save us five dollars a day by picking up small tools instead of sweeping them out.

Years later he wrote:

Unless an industry can so manage itself as to keep wages high and prices low it destroys itself, for otherwise it limits the number of its customers. Ones own employees ought to be ones own best customers. The real progress of our company dates from 1914, when we raised the minimum wage from somewhat more than two dollars to a flat five dollars a day, for then we increased the buying power of our own people, and they increased the buying power of other people, and so on and on. It is this thought of enlarging buying power by paying high wages and selling at low prices that is behind the prosperity of this country.

which he did in collaboration with Samuel Crowther in 1926. The complete theory had by that time arrivedthe theory, namely, that the wage earner is more important as a consumer than as a producer. How much of that formulation was Fords and how much of it Crowthers one cannot say. They wrote several books together, with Ford speaking in the first person as I or we, and the ideas were entirely his own, but as he conceived them they were wordless revelations or sudden flashes of insight. It was Crowthers part to clothe them with reason and argument and house them in proper premises.

Ford knew something about the behavior of his own mind. He would say: We go forward without the facts. Or: We learn the facts as we go along.

To which Crowther would add some rhetorical phrases on vision for the pioneer and facts for the plodder.

I once asked Ford where ideas came from. Did he beat them out of his head or stare them out of a blank wall?

There was something like a saucer on the desk in front of him. He flipped it upside down and kept tapping the bottom with his fingers as he said: You know atmospheric pressure is hitting there at fourteen pounds per square inch. You cant see it and you cant feel it. Yet you know it is happening. Its that way with ideas. The air is full of them. They are knocking you on the head. You dont have to think about it too much. You only have to know what you want. Just suspend in your mind the thought of what it is you want. If you do that, then you can forget it. You can go about your business thinking and talking of other things, and suddenly the idea you want will come through. It was there all the time.

Next page