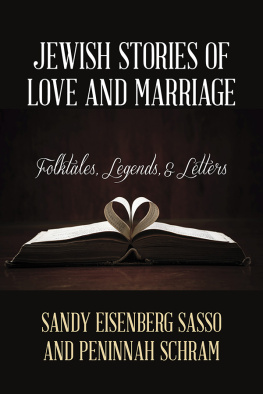

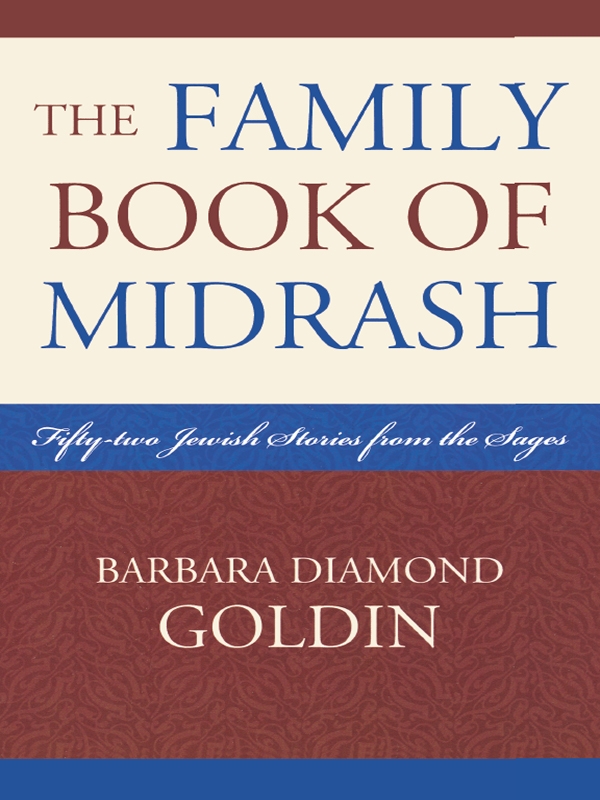

Barbara Diamond Goldin currently teaches language arts to middle school students at Heritage Academy in Long Meadow, Massachusetts. She is the author of eleven childrens books, including Night Lights: A Sukkot Story; nonfiction such as Bat Mitzvah: A Jewish Girls Coming of Age; historical fiction such as Fire: The Beginnings of the Labor Movement; and collections of stories, including Creating Angels: Stories of Tzedakah. Her books have received such awards and recognition as the National Jewish Book Award (for Just Enough Is Plenty: A Hanukkah Tale ); the Sydney Taylor Picture Book Award (for Cakes and Miracles: A Purim Tale ); and the American Library Association Notable Book Award for 1995 (for The Passover Journey: A Seder Companion ). She lives in western Massachusetts with her two children.

Bibliography

Adelman, P. V. (1986). Miriams Well: Rituals for Jewish Women Around the Year. Fresh Meadows, NY: Biblio Press.

The Babylonian Talmud (1938). Trans. Rabbi I. Epstein. London: Soncino.

Braude, W. G., trans. (1959). The Midrash on Psalms. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Chanover, H., ed. (1985). Home Start. New York: Behrman House.

Cherry, K. (1972). Lessons from Our Living Past. New York: Behrman House.

Encyclopedia Judaica (1972). New York: Macmillan.

Feldbrand, S. (1980). From Sarah to Sarah. Brooklyn, NY: Eishes Chayil Books.

Frankel, E. (1989). The Classic Tales: 4,000 Years of Jewish Lore. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Freehof, L. (1988). Bible Legends: An Introduction to Midrash. New York: UAHC Press.

Gaster, M. (1968). The Exempla of the Rabbis. New York: KTAV.

(1981). Maaseh Book: Book of Jewish Tales and Legends Translated from the Judeo-German. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America.

Gerlitz, M. (1980). In Our Fathers Ways. Jerusalem, Israel: Oraysoh Publishers.

Ginzberg, L. (1988). Legends of the Jews. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America.

Harlow, J., ed. (1979). Exploring Our Living Past. New York: Behrman House.

Hauptman, J. (1974). Images of women in the Talmud. In Religion and Sexism, ed. R. Ruether, pp. 196210. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Henry, S., and Taitz, E. (1988). Written Out of History: Our Jewish Foremothers. Fresh Meadows, NY: Biblio Press.

Marenof, M. (1969). Stories Around the Year. Detroit: Dot Publications.

Midrash Rabbah (1983). Trans. Rabbi H. Freedman: New York: Soncino.

Mimekor Yisrael: Classical Jewish Folktales (1976). Coll. M. J. bin Gorion, ed. E. bin Gorion, trans. I. M. Lask. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Patai, R., trans. (1988). Gates to the Old City: A Book of Jewish Legends. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer (1965). Trans. and annot. G. Friedlander. New York: Herman Press.

Prose, F. (1974). Stories from Our Living Past. New York: Behrman House.

Segal, Y. (1976). Our Sages Showed the Way. New York: Feldheim.

Serwer-Bernstein, B. (1987). Lets Steal the Moon. New York: Shapolsky.

Taylor, S. (1980). Danny Loves a Holiday. New York: Dutton.

Weissman, R. M. (1980). The Midrash Says. New York: Benei Yakov Publications.

(1986). The Little Midrash Says. New York: Benei Yakov Publications.

The Animals in the Ark

B uilding the ark was a big job for Noah, but loading the ark with two of each kind of animal was an even bigger job. The most difficult job of all, however, was feeding the animals.

There were so many different kinds of animals in the ark, and each one had to be fed a particular kind of food. This one ate hay, that one berries; this one grains, that one meat. Some animals ate in the daytime and others only at night.

Day and night, Noah and his wife and their three sons and their sons wives were busy feeding the animals. Often they did not even have time to feed themselves.

Sometimes an animal became ill and needed special attention, like the lion who developed a fever. And sometimes an animal would not eat the food Noah put in front of it. This was the case with the little chameleons.

Noah gave them berries.

But the chameleons did not touch them.

Noah offered seeds and grasses.

The chameleons didnt touch these either.

He gave them leaves, and straw, and meat, but still the little chameleons wouldnt eat them and they grew pale and smaller.

Noah worried about the little chameleons. He was afraid they might die. Often he would stand by the lizards and talk softly to them.

If only you could tell me what you need, he would say.

But the chameleons said nothing, because, of course, they cannot speak as humans do.

One day when Noah came to see the chameleons, he was carrying a pomegranate with him, intending to eat it. With all the animals braying and cackling, screeching and howling for their food, Noah just grabbed what he could for himself and ate wherever he stood.

Noah suddenly noticed a little hole in the pomegranate and sure enough, as he sliced around it, a little worm wiggled out and fell to the floor. Immediately, the chameleons came to life. They raced forward, flicking their tongues, and caught the worm and ate it.

Noah was delighted. Now I know what to feed you, little ones.

From then on, Noah saved any food that grew wormy for the chameleons and they grew healthy. Their green and blue scales shone brightly again.

Noah and his family continued to feed and take care of all the animals until the rains ended and the waters receded. When at last he and his family and all the creatures left the ark, Noah felt a great relief. No longer would he be responsible for feeding all these animals. Now they could find their own food in Gods worldin the forests, the fields, the swamps, and the dry places.

Sanhedrin 108b

How Dishonesty Entered the Ark

N oah stood by the ark that he had built at Gods command, helping all the living creatures board. They boarded in pairs, a male and a female from each species.

Along with the lions and tigers, eagles and cranes, butterflies and lizards came Dishonesty, a shadowy, nearly transparent figure.

Dishonesty crept alongside the lizards toward the boat.