First published in the United States of America in 2017

by Chronicle Books LLC.

First published in France in 2014 by ditions du Chne

Hachette Livre as Le Petit Livre de Nol.

Text 2014 by ditions du ChneHachette Livre.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data available.

ISBN 978-1-4521-6163-1 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-4521-6569-1 (epub, mobi)

Cover design by Lizzie Vaughan

Typeset by Howie Severson

Translated by Deborah Bruce-Hostler

All reproductions in this book are from the private collection of ditions du Chne, except Collection Kharbine-Tapabor.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

THE LONG HISTORY OF CHRISTMAS

For many, Christmas is a quintessential family holiday, an occasion to make a special effort, to gather together, to exchange gifts, and, above all, to indulge the children. It is, however, no less and foremost a Christian celebration. It is said that Christmas was first established as a holiday in the fourth century, when Pope Liberius proclaimed the twenty-fifth of December as the official birthdate of Jesus. No precise historical account supports this claim, but when the pope declared the twenty-fifth a holy day, the Church, in effect, was acknowledging the popularity of pagan celebrations that welcomed the winter solstice. The date and the celebration soon became an essential part of Christian custom.

RITUALS AND FEASTING

In the fifth century, the Christian Church introduced observance of Advent. During this season, originally seven, then four weeks long, the faithful prepared themselves to greet the newborn Savior by fasting and praying. Yet they did not neglect to fill their pantries, for Christmas was already synonymous with feasting. In the Middle Ages, pagan traditions, such as the Feast of Fools, survived among holiday pastimes. The Church, which took a dim view of the accompanying exuberant activities, outlawed them.

Around the twelfth century, an enduring custom began in Europe: that of the Yule log or, in French, the bche de Nol. A very large log would be lit at the hearth and had to continue burning for three days. The ritual varied among different regions, but everywhere the log was tended with great care, since the outcome of the year to come depended on its proper burning. In nineteenth-century Europe, wood-burning hearths fell from use, making the Yule log obsolete. Pastry chefs memorialized the custom by creating a holiday cake in the form of a log, still called the bche de Nol.

With the old Yule log glowing in the fireplace, families and neighbors gathered at Midnight Mass, called there by the church bells. Upon returning home, all would sit down to a Christmas Eve repast. Once frugal, through the centuries the Christmas Eve meal became a feast. The roast goose, a vestige of Roman winter solstice celebrations, played a lead role in many countries. The turkey, a newcomer imported from the Americas in the sixteenth century, later dethroned the goose in many places in Europe. Sugary sweets have been gifts since the Middle Ages. The Church imposed a prohibition during Advent against using eggs, butter, or milk in cakes. This did not limit the imagination of pastry cooks in the least; they made spice cakes and sweet biscuits, still essential to the season in Northern Europe.

THE ARRIVAL OF FATHER CHRISTMAS

The fir tree at Christmas recalls pre-Christian traditions. For the ancient Celts and Vikings, the conifer signified the ever green vitality of Nature. Around the seventh century Christians adopted it as a symbol of the Tree of Paradise. In those earlier times, the cut tree, decorated with apples, enlivened public squares in winter. Beginning in the sixteenth century, the fir tree was brought inside to decorate the house for Christmas. Apples and candies were gradually replaced by more and more sophisticated decorations for the tree, many with no religious significance. But candles were used on Christmas trees for centuries, reminding the faithful of the light that they believed the Savior brought to the world. Eventually strings of lights replaced the candles.

Since the late nineteenth century Christmas has become an increasingly secularin fact, commercialholiday. This change was marked by a new arrival: Father Christmas, Santa Clausor Pre Nol in France. What inspired this old gentleman was the popular belief that prevailed well before the Christian era that aged figures, sprites, or bearded supernatural beings sometimes bestowed the young or the old with gifts. But more than Celtic forebears or the Scandinavian Julenisse, Father Christmas merged traits from traditions celebrating the December sixth feast day of Saint Nicholas and loaned them to the Anglo-Saxon Santa Claus. Around 1850, the North American illustrator Thomas Nast gave Santa Claus his defining look: rotund silhouette, jovial face, and red and white suit. The Coca-Cola Company popularized the image in an ad campaign in 1931.

Until the early twentieth century, gifts were commonly exchanged at New Years, with children receiving no more than the adults. With the coming of Pre Nol or Santa Claus and with the influence of new, large department stores, gift giving grew exponentially. Adults as well as children were given presents on December twenty-fourth or on Christmas Eve, and the ancient tradition of New Years gifts faded little by little.

ACROSS THE WORLD

Saint Nicholas was never completely eclipsed by Santa Claus. In Northern Europe, the arrival of Saint Nicholas on December sixth still brings joy, even though he is accompanied by a sinister counterpart, known in France as Pre Fouettard (Father Whipper). Warmly welcomed in different countries at this season are Christkindel in Alsace, the witch La Befana in Italy, Saint Lucy in Sweden, and Babouschka in Russia. The merrymaking that accompanies their transit earlier in December does not detract from the celebrations of Christmas itself; all is a part of the holiday season that stretches through the month of December and into the early days of January. Religious rites, pagan traditions, and secular customs coexist, just as plans for Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, the decorations, and the meals vary according to region or country. But rarely do those who celebrate Christmas leave out gift giving.

DECEMBER TWENTY-FIFTH

THIS DAY, CHOSEN BY THE CHURCH IN THE FOURTH CENTURY, COINCIDED WITH PAGAN CELEBRATIONS OF THE SOLSTICE.

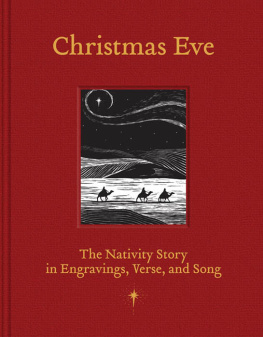

No ancient document gives a precise account of the date of Jesuss birth. This did not bother the early Christians, who gave their attention to the death and Resurrection of their messiah. A passage in the Gospel according to Luke describes the shepherds guarding their sheep near the stable where Mary and the infant Jesus were sheltered. This detail does not argue in favor of the twenty-fifth of December, since in Judea flocks returned from the hills at the end of autumn. But this is the day made official by the Catholic Church in accordance with the decree of Pope Liberius in the year 354. The Church hoped that the ardor of pagan celebrations of the winter solstice, occurring close to this time of year, would translate to a new Christian holy day. The goal was soon fulfilled with acceptance of celebrations of the day; nonetheless, some still refute the inexact decision on when to celebrate the birth of Christ.

Next page