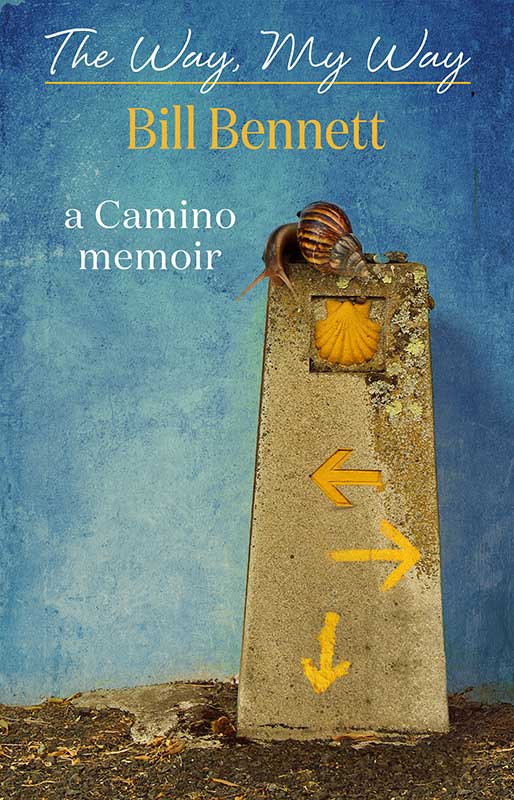

Cover

Chapter 3

I dont understand snoring.

I dont understand the need for it.

Perhaps from an evolutionary standpoint I can see how snoring might have developed as a defence mechanism, to keep the species alive by warding off mammoths and other prehistoric beasts while our ape forebears slept in their caves.

That night there was a snorer in the room that definitely would have frightened off a mammoth. The offender was a young lady named Victoria, who Id met briefly over dinner. Perhaps it was her defensive mechanism, to keep men away.

It certainly worked with me.

Her snoring was so violent it would have registered on the Richter scale in an undersea laboratory in Hawaii. If wed been closer to the ocean I would have worried about tsunamis.

I jammed in some earplugs and went back to sleep, and dreamt of woolly mammoths stampeding over frozen plains, being chased by pilgrims wielding gnarled tree branches, using giant scallop shells for shields.

I woke bright as a button at 2:21am. I felt short changed. The Universe had short changed me a minute. Why hadnt it woken me at 2:22am? That would have been propitious for the first day of my Camino. No, it woke me a minute too soon.

It didnt bode well.

Victoria was still snoring. It wasnt so much that I could hear her, but I could feel the pressure on my earplugs, like standing beside a jackhammer. A couple of fillings in my teeth were starting to work their way loose. I noticed a glass of water on a nearby table was shaking, as if a dinosaur were approaching.

Everyone else was asleep.

How can they sleep when theres a T-Rex coming?

The albergue had a policy that no-one was allowed up until 6:45am. That enabled other pilgrims to get a good nights sleep before the first big day. But I was jetlagged, and couldnt go back to sleep. Which meant Id have to lie in bed for more than four hours, enduring Victorias attempts to move the earths tectonic plates.

Id found out the previous evening that a hospitalero from the albergue always did a bread run at 6am to the local bakery. This was my chance to get out of bed early, before Victorias nasal passages rendered the albergue structurally unsound and the roof caved in on me. I would volunteer to go to the bakery too.

I loved French village bakeries. And I particularly loved them very early in the morning, when they were in full production. I loved the smell of them. There was something very honest about local artisan bread.

So at 6am on the dot, bleary-eyed and slightly disoriented, as though Id been standing near a mine site during three and a half hours of blasting, I got up and headed off to the bakery with Michelle, a lovely middle-aged lady whod previously walked the Camino, and was now working at the albergue as a helper.

The lanes were dark and empty as we made our way to the bakery on the other side of town, the dew on the cobblestones reflecting the occasional street lamp. We passed houses and shopfronts that wouldnt have looked much different two hundred years ago. Our footfalls echoed. In the cold, our misty breaths ballooned in front of us, and disappeared as we walked through them.

Suddenly I had to stop.

Ahead of me were the towns massive stone gates gates that had stood for centuries, and through which millions of pilgrims had passed on their way to Santiago. Id seen these very gates countless times in photos and on videos. And now there I was, standing before them.

I was overwhelmed.

Later that morning, I too would set off through those gates to begin my own pilgrimage, following in the footsteps of some of Europes great men and women of history. I felt a part of something so huge, so timeless, so reverent it was awe-inspiring. But it was also confusing.

Why are you here Bill? Why are you doing this?

I didnt know.

I did not have a clue as to why Id just dropped everything, all my work commitments back home, to head off halfway around the world to do a pilgrimage. It was a complete mystery to me. Yet if I needed confirmation I was doing the right thing, it came when I made the travel booking.

After thinking about walking the Camino for so long, the dam finally burst and I made the decision. I just had to do it. I would leave in six weeks. So I called my travel agent and booked two coach fares, one for me and one for my wife, who would join me in Santiago at the end. The total cost came to $4,194.

Not long after, my PGS alerted me that for some reason, I should check my bank account. When I did, I discovered that shortly after Id paid for the airline tickets, I received a deposit into my account of $4,392.

At first, I thought it was a mistake, and I went to call the travel agent to let him know the money for the airfares had bounced back. But then I realised the funds were actually a royalty payment for a past film.

I dont get royalty payments often, sadly. I certainly dont get them within an hour of making a payment to go on a pilgrimage. And I sure as hell dont get them $198 more than the cost of the airfares, that $198 being the amount I needed to cover my ground transportation.

In other words, within an hour of paying my airfares to walk the Camino, I got all my transport costs covered. Out of the blue. I was gobsmacked. But it told me clearly that I was doing the right thing. That Id been called to do this walk.

I stepped inside the bakery with Michelle. The smell of freshly baked croissants and brioches swirled around me. The floor was dusted with white flour. Stacked against a wall were baskets and brown paper bags full of baguettes and pastries, ready for pick-up by the various stores and albergues around the town.

Michelle grabbed her bag and we began to walk back. It was still dark, but pilgrims were now starting to leave St. Jean making their way through the town gates and across the old stone bridge out of town, heading to Roncesvalles. They were moving slowly, yet with a quiet determination.

They had their backpacks on, and their staffs and trekking poles, and as they passed us they nodded and smiled distractedly, their focus clearly on what lay before them - the days climb over the Pyrenees.

At that moment, seeing these pilgrims leaving for the big climb, I wanted to race back to the albergue, throw on my backpack and just leave. Follow them. Head off to Roncesvalles too.

But I had a booking that night at Orisson. And Id promised my wife that Id ease into it. Doing the 8km walk would be my first demonstration to her that I was breaking old habits, that I wasnt a bull charging at gates anymore.

So I helped Michelle carry the bags back to the albergue, and I had breakfast.

I popped back into the bunkroom, where the other pilgrims were packing up and getting ready to head out. I caught Victorias eye, and said to her kindly:

Hey Victoria, do you realise that you snore?

I thought I was performing a public service, telling her on the first day so she could remedy the situation and not put other pilgrims lives at risk. But she turned to me, looking like she was about to explode. So did Rosa, so did every other pilgrim in the room.

You snore! they all said in unison, trying to suppress their anger and rage.

Confused, and hurt, I said: What do you mean?

YOU SNORE! they shouted, eyes blazing.

It was lucky there wasnt a rope handy. Red-eyed and exhausted from lack of sleep, they looked ready to lynch me. Even Rosa - my taxi-sharing Rosa.