INTRODUCTION

DANA SPIOTTA

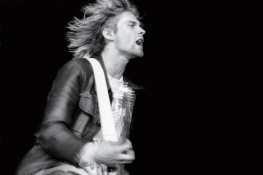

It is one of the jobs of the young to rail against the failures of the previous generation. You can trace a particular line of concern from Holden Caulfield in 1951 to Nirvana in 1991: phonies, conformists, squares, the establishment, the Man, the mainstream, yuppies, corporate culture, poseurs, fakes, sell-outs. The concern comes down to an ideal of authenticity, with maybe the worst sin being hypocrisy. Capitalism has always absorbed and appropriated dissent and resistance, which is why they have to constantly be reinvented in subculture. Nirvana and Kurt Cobains version in the 1990s was perhaps an apex, and also when tensions within that concern became unsustainable. Afterward, future critiques would have to be differently conceived.

Cobain, like other kids growing up after Vietnam, after Watergate, after the counterculture, absorbed a jaded, knowing quality. An obsession with irony coexisted with an obsession with authenticity. Satire became ubiquitous: Mad magazine (full of take-offs ridiculing everything from blockbuster films to TV ads), Wacky Packages (stickers on cards that kids collected that had fake advertisements for joke versions of products) and Saturday Night Live, which in 1975, its inaugural year, featured Jerry Rubin, the Yippie, in a fake commercial selling wallpaper with hippie and anti-establishment slogans on it. The joke was that Jerry Rubin had sold out, and somehow his knowingness made it okay, but that cynical stance contained a form of surrender. That version of the left seemed to give up. And in fact, Reagan and Thatcher were just around the corner.

Punk rock offered a giant refusal to that cynicism while still cloaking itself in irony. In 1977 the Sex Pistols released the ironically titled single, God Save the Queen. Johnny Rotten famously sneered as he asked his audience, Ever get the feeling youve been cheated? The sneer insured that the joke was complicated: the Pistols were cheating the audience because they defiantly refused to please, but also that the culture had cheated all of them and left them with a kind of nihilism. There was a lot of spitting going on: gobs at the band and gobs back to the audience. As punk developed, it retained its nihilist refusal, but it also had a more egalitarian side. Lester Bangs wrote about the Clash inviting their fans to share their hotel room with them. They were not arena-rock gods, they were just a garage band. Virtuosity on your instrument was not the point, but being politically virtuous was. And it is this strain of punk purity that carried into the 1980s as a counter to the materialist corporate culture of the Reagan years.

There were always traps contained in that youthful fervor for authenticity: how to identify authenticity, first of all, and then how easily markers of authenticity can become just another pose, full of clichs (the hallmarks of hackery). Kurt Cobain, in these interviews that start in 1990, the year before Nirvana made the big time, and end two months before he died in 1994, had internalized the punk rock of the 1980s in the indie/alternative underground, and we see him grapple with trying to be true to his punk-rock ethics. But it was impossible: one must have the irony, the ambivalence of not caring, of admitting your own complicity in the system. At the same time, one had to care, and follow very strict rules for not selling out. You had to be like Calvin Johnson, maybe, obscure but respected. Kurt Cobain might have been the last person who believed in punk, and he grew weary navigating these tensions. Besides, there was something art-school and elitist in cultivated obscurity, wasnt there? Punk should not be elite (this is the problem with a subculture often defined by what it is not).

One of my favorite threads of punk ethos perhaps came from the Stooges and was picked up on by the Replacements: proud loser-dom. It was a sly form of anti-capitalism, of resistance to the 1980s worship of avarice and material, amoral success. This is illustrated in the famous Sub Pop T-shirt that said loser in all caps and extends to Becks 1994 hit, Loser. And we can hear this self-deprecation when Cobain says Nirvana is lazy and illiterate and would lose an argument about any topic because they took too much acid and smoked too much pot. This is self-deprecation as liberation and subversionthe bullied kids appropriating the words that once were hurled at them. But it is also a kind of pose, as if they didnt want to get caught caring about anything too much. You cant criticize my songs cause I already said I suck and cant play. Like all of these threads, its complicated. Kurt Cobain may not have been schooled in music or literature, but he was good. He was proud of the albums, if not proud of anything else.

But his humility was also real. After the traumatic divorce of his parents (the legendary divorce is such a bore he professed in Serve the Servants), he led an itinerant existence, even living in his car sometimes. He was a high school dropout, worked as a janitor, but was mostly unemployed. The thing that saved him, the place he began and finished, was music. He was a true believer in music as a space where he could be himself. He began with total commitment to writing songs, playing his guitar, and performing. And he knew how he wanted the music to sound. He wanted it to be like the music he loved: raw and hard but with pop hooks and lyrics you could hear over and over and still find oddness and interest in them. As much like the Beatles as Black Flag, which turned out to be very appealing to a big audience. The problem was what the world did with the music, with selling the music, and with promoting the music. Ultimately, in his interviews, you can see him trying to work that part of it out. He doesnt want an image. And, as in his lyrics, he manages sarcasm and ambivalence while also exposing how much he cared, a lot, about everything, and constantly. While this worked in his songs, it was harder to pull off in his life. In interviews, he often lied or obscured while also being almost compulsively honest, vulnerable, a person in pain who kept confessing and pouring his heart out even as he felt betrayed by the press and unnerved by his fans.