A Special Faculty Development Assignment from the University of Texas at Dallas facilitated the completion of this book.

I wish to thank Dr. Alex Vernon for reading the Hemingway chapter () and Gary Kass, of the University of Missouri Press, for his careful editing and cogent suggestions. Interlibrary Loan at McDermott Library, University of Texas at Dallas, was especially helpful in obtaining materials expeditiously. And, as always, I thank my wife, Florence, for her tireless efforts in reading and editing the many drafts of this book.

Introduction

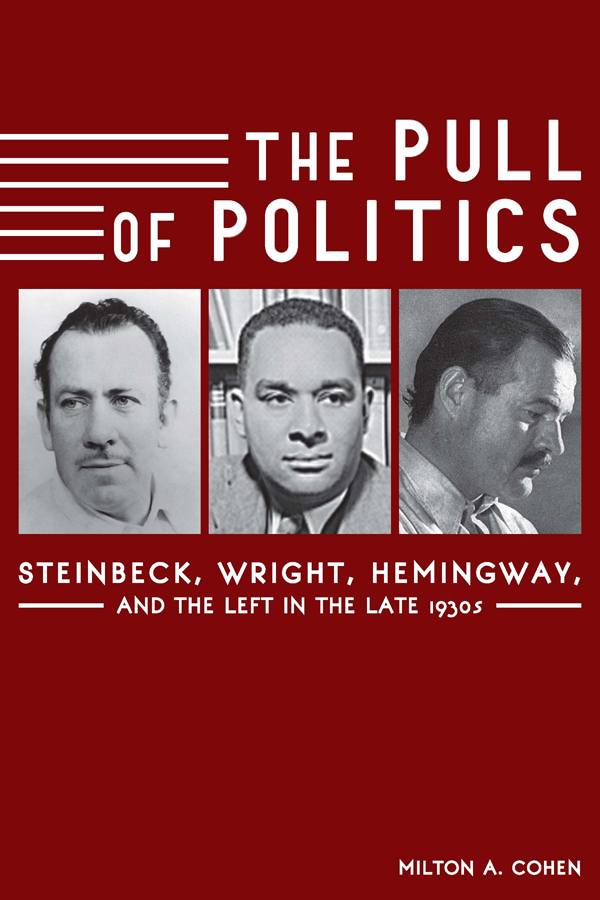

CULMINATING A TUMULTUOUS decade, the years 1939 to 1940 witnessed the publication of three major novels that achieved the distinction of being both popular and critical successes: The Grapes of Wrath (1939), Native Son (1940), and For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). All three were runaway best-sellers; all three were made into films; two (For Whom the Bell Tolls and, remarkably, Native Son) were Book-of-the-Month Club selections; and The Grapes of Wrath won the Pulitzer Prize in 1940 and the National Book Award in 1939.

Although set in different locales and addressing different sociopolitical issuesthe plight of migrant farmers in Oklahoma and California, a black mans killing of a white woman in Chicago, and Loyalist partizans fighting in the Spanish Civil Warthese novels and their authors share important similarities, which, in turn, tell us something about American literature and politics at the end of the 1930s. All three novels have highly political themes and slants that, in their individual contexts, can be construed as leftist.entire life. The only people willing to help him are communists or fellow travelers. The Spanish Civil War was of course explicitly political, as the fascist Rebels (or Nationalists) led by General Franco and supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy attacked a democratically elected coalition of leftist groups (the Republicans or Loyalists), whose military leadership and matriel came mostly from the Soviet Union. The independent protagonist of For Whom the Bell Tolls, Robert Jordan, like Tom Joad in Grapes, learns the value of collective action by working with a group of Loyalist partizans to carry out his mission. But he also deals directly with, and gives his allegiance to, the covert Soviet leadership in Spain, which has imported Stalinist tactics.

The Pull of Politics situates each novel within the political development of its author: the personal and historical events that awakened his commitment to a leftist cause; his earlier literary works reflecting stages of that commitment; and, following analysis of his major novel, the biographical and historical events that ultimately severed that commitment.

Despite their shared move toward various kinds of leftism, the authors political views and history would seem to make them an anomalous grouping. TwoJohn Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingwaywere relatively apolitical before they encountered the issues that pulled them to the left.and reflect, in varying ways, a larger crisis in the Left at precisely this period.

Another important quality linking the three writers is that all were attracted to the Left by one or two particular appeals rather than by a broad-based ideological agreement with communist doctrine. For Steinbeck and Hemingway, these appeals were the issues depicted in their novels: the mistreatment of the migrant farmers and the Spanish Loyalists struggle against fascism. For Wright, also, the central issue that kept him in the Communist Party was not communist ideology in general but the CP-USAs actions to improve the status of blacks in America.

Two of these writers were also drawn left by self-interest. The personal benefit to Wright was obvious: the Chicago John Reed Club gave him his start as a writer, encouraged him, and provided a sympathetic audience and publishing venues in leftist literary magazines. To hold office in the club, he had to join the CP-USA. The benefits Hemingway received in gravitating to the Left were less obvious, but nonetheless distinct: leftist critics who had lambasted his indifference to the Depression and hostility to the Left in Death in the Afternoon (1932), The Green Hills of Africa (1935), and in his Esquire magazine articles now celebrated his political commitment to Loyalist Spain. Even before that war began, Hemingway made quiet overtures to the Left while still proclaiming his political independence.

The three authors shared other political ties to the Left. All three publishedor attempted to publisharticles in communist newspapers: the San Francisco Peoples World for Steinbeck; Pravda for Hemingway; and the Daily Worker for Wright, who, as its Harlem editor (actually, a reporter) in 1937, published hundreds of brief articles there. Hemingway and Wright also published works in The New Masses, the CP-USAs literary magazine and, for most of the 1930s, the most influential journal of the American Left. Further, in their journalistic work, both Wright and Hemingway supported Stalinist positions (Wright generally, Hemingway regarding the Soviet Unions political priorities in the Spanish Civil War). All three authors joined the League of American Writers, a group created by the American Writers Congress in 1935 (both groups, in turn, fronting the CP-USA). Steinbeck joined in 1937, was elected to the

They were far from being true believers, however, for each author held conflicted attitudes that complicated his pull to the Left. Despite believing that collectivism would enable the migrants to prevail over the big landowners, Steinbeck had long distrusted group thinking and behavior (which he termed the phalanx) and admired the detached observer and the migrants individualism. Wrights burgeoning identity as an independent author, needing time to write and express his own themes, conflicted with the Communist Partys rigid expectations of its authors and its directives commanding their time. Hemingways characteristic need for independent thought and action did not cohere with his support of authoritarian Soviet leadership in Spain and even less with his decision to parrot the Party line in his journalism and early fiction about the war. All of these topics will occupy ).

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.