CONTENTS

About the Author

Since 1956, New Scientist has established a world-beating reputation for exploring and uncovering the latest developments and discoveries in science and technology, placing them in context and exploring what they mean for the future. Each week through a variety of different channels, including print, online, social media and more, New Scientist reaches over 5 million highly engaged readers around the world.

Follow New Scientist on Twitter: @newscientist

Also from New Scientist

Does Anything Eat Wasps?

Why Dont Penguins Feet Freeze?

Do Polar Bears Get Lonely?

Why Cant Elephants Jump?

How to Make a Tornado

How to Fossilise Your Hamster

Farmer Buckleys Exploding Trousers

Chance

Question Everything

How Long is Now?

The Origin of Everything

How to Be Human

This Book Will Blow Your Mind

The Brain

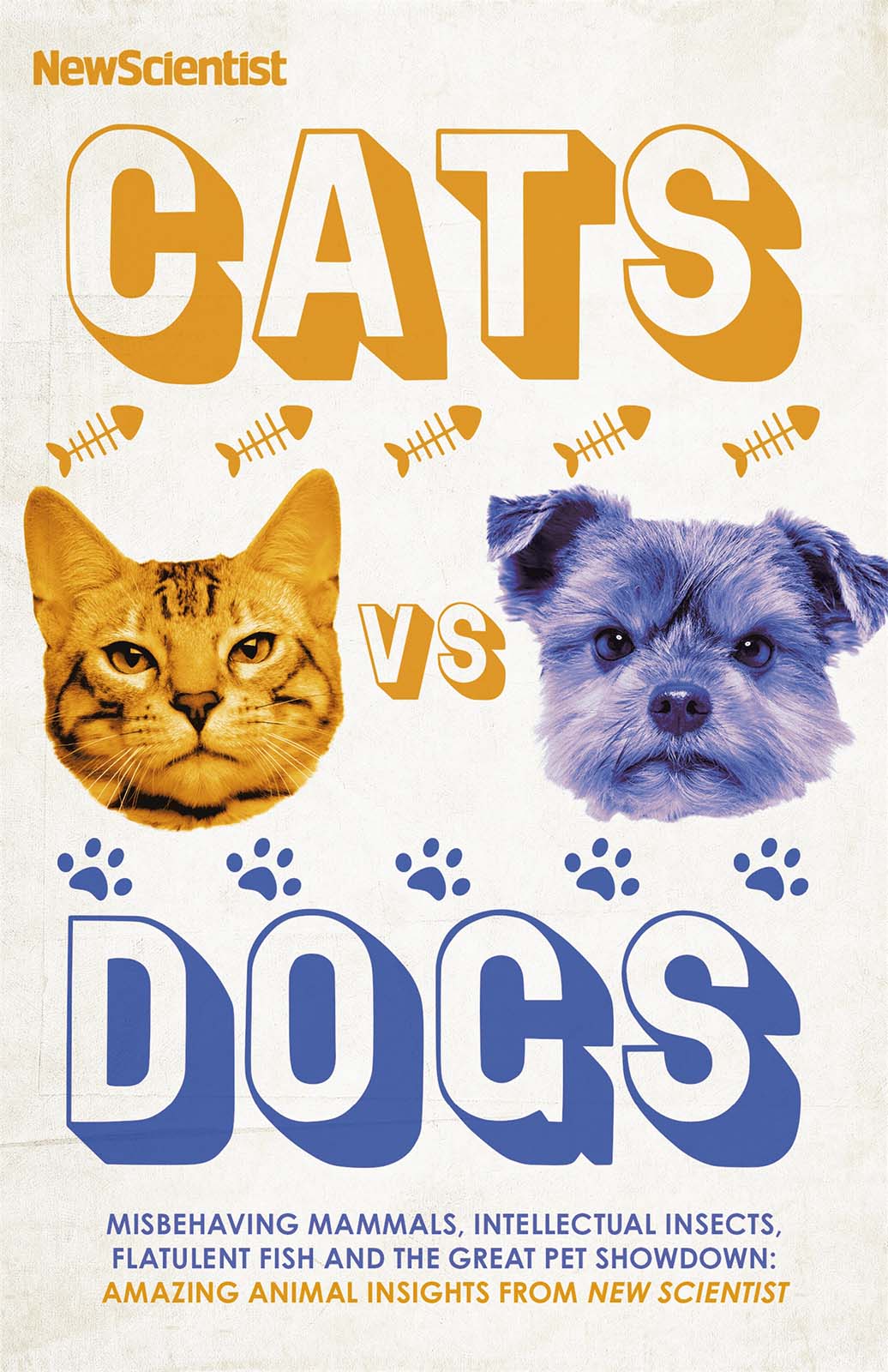

CATS VS DOGS

Misbehaving mammals, intellectual insects, flatulent fish and the great pet showdown: amazing animal insights from New Scientist

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by John Murray (Publishers)

First publishing in the United States of America in 2021 by Nicholas Brealey Publishing

Imprints of John Murray Press

An Hachette UK company

Copyright New Scientist 2020

The right of New Scientist to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Cover image: Shutterstock.com

From material previously published in Does Anything Eat Wasps?; Why Dont Penguins Feet Freeze?; Do Polar Bears Get Lonely?; Why Cant Elephants Jump?; How to Make a Tornado; How to Fossilise Your Hamster; and Farmer Buckleys Exploding Trousers

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

UK eBook ISBN 978 1 529 33921 5

US eBook ISBN 978 1 529 34148 5

John Murray (Publishers)

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.johnmurraypress.co.uk

Nicholas Brealey Publishing US

Hachette Book Group

Market Place Center, 53 State Street

Boston, MA 02109 USA

www.nbuspublishing.com

INTRODUCTION

At New Scientist , we always like to say that facts matter. Since the magazine was founded in 1956 for all those interested in scientific discovery and its social consequences, our mission has been to bring facts, evidence and rational thinking to bear on the weightiest issues of the day, from the dawning of the nuclear age and the cold war space race, to climate change, the search for sustainable energy sources and the odd global pandemic.

And, indeed, whether cats are better than dogs.

I well remember when this first became a topic of conversation in the New Scientist office one lunchtime about ten years ago. We all know the world divides into cat people and dog people, and for us it was no different. Arguments were advanced, battle lines were drawn, tempers frayed. The result was an unsatisfactory stalemate.

Here, though, was surely a question where science could be usefully brought to bear. Check mission statement. And so we devised a scheme of ten objective criteria by which to judge our furry friends, and set out to contact the worlds leading experts on canine and feline behaviour to settle the question once and for all.

It was perhaps, with hindsight, a mistake that the editor in charge was vehemently a dog person. I recall her disappointment when the scores were on the kennel doors, and it was a 55 draw. (That was one point to the dogs, incidentally, tractability you can keep them in kennels and they wont complain.) I also remember my surprise at seeing the article in the magazine. A mysterious eleventh category had been added to gift the mutts the victory. Facts matter clearly only up to a point.

Far be it from me to impugn a colleagues journalistic integrity, however; alls fair in (pet) love and war. And while few questions seem to get animal lovers so hot under the collar as that of cats vs dogs, the animal kingdom more broadly is an endless source of fascination for New Scientist readers. We know that from how often fur and feathers feature in our weekly Last Word column, in which readers send in everyday science questions to be answered by others. The Last Word column has been the source of a series of bestselling books over the years, all of which tended to have animal-themed questions as their titles, many of them reproduced here. Do polar bears get lonely? Can elephants jump? Why dont penguins feet freeze? And does anything eat wasps?

The idea of this book was to collate some of the best of those animal-themed queries in one place, together with a few bits and bobs that have popped up in the magazine over the years catnip, we hope for the animal lover.

But the informative, intriguing and often witty insights of our readers take pride of place, providing a breadth of wisdom thats hard to achieve by conventional (or unconventional; see above) journalistic methods alone.

Or, indeed, asking the questions it never occurs to journalists to ask. Can hamsters solve the climate crisis? Do magpies prefer semi-skimmed milk? Has a fish ever been struck by lightning? And where are all the Argentinian ants? (That one delightfully answered by Harvard entomologist Edward O. Wilson, the worlds foremost authority on ants.) I never thought I needed to know those things but I think I do now. The joy of science.

What makes animals so fascinating? (Thats me asking a question now.) My guess is its because we can never be them. The philosopher Thomas Nagel once asked another famous rhetorical question, What is it like to be a bat?, when grappling with the intractable problem of what consciousness is, human, animal or otherwise. The short answer is that we cant know we are left with a fascinating guessing game about why animals behave as they do, and what theyre thinking and feeling as they do it.

That is a reminder that we are just one species among many on a startlingly, beautifully, biodiverse world. Its up to us to ensure it stays that way. To strike a more serious note, much has been made of how we are entering a new era in Earths history, the Anthropocene, in which human activities are likely to dominate the geological record. Accompanying it, unless we learn to live more in harmony with the natural world on which we ultimately depend, could be a sixth mass extinction of life the only one caused by the activities of a dominant species. For every entertaining question about the animal world around us, there are serious questions to be asked about our treatment of it.

But lets stay on the side of delight for the moment. It only remains for me to thank all my New Scientist colleagues, our readers and all contributors to the magazine over many years who make books like these possible. Thanks also to Kate Craigie and Georgina Laycock at John Murray for making this one happen. I hope you enjoy it and if youd like your own question, big or small, answered, why not email it to ?