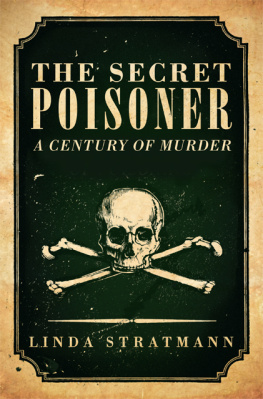

Essex

M URDERS

Linda Stratmann

To John,

Essex boy extraordinaire

First published in 2004 by Sutton Publishing Limited

Reprinted in 2008 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Reprinted 2009, 2010, 2012

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Linda Stratmann, 2004, 2013

Series Consulting Editor: Stewart P. Evans

The right of Linda Stratmann to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8451 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

E ach of these ten tales of murder in Essex reveals something of the rich history of the county, and the variety of its landscape. Salt-marshes, a doomed airfield, a protected forest, cornfields dotted with windmills, sandy beaches, industrial townships, country manors and lonely roads may all provide the backdrop to murder. Some of these stories are being anthologised for the first time, and I make no apologies for omitting the better-known and often-told tales in favour of the freshness of these new classics. We all love a good story, and for drama, the human touch and the occasional dizzying twist, these are unbeatable. And they are all true.

I have used only contemporary documents as my sources accounts of inquests and trials which were fully reported in pamphlets and newspapers of the day, the memoirs of Superintendent Totterdell who personally investigated three of the cases, and documents held in local study archives, the Essex Police Museum, the Family Record Centre, the Essex County Archives, and the United States Army Judiciary.

COLCHESTER JACK, 17446

S mugglers have usually enjoyed a romantic reputation, and few more so than John Skinner. Well-known among his fraternity in Boulogne as Saucy Jack or Colchester Jack, he was the Casanova of smugglers. Handsome, and well dressed, he no doubt had manners which women found attractive, for he was adept at enticing married ladies from their husbands, and deluding single women that they were the sole object of his attentions.

He was born in Brightlingsea, in 1704, the son of John and Mary Skinner, sound middle-class folk, who did everything good parents should have done to teach him that advancement should come through honesty and hard work. He was provided with a good education, and in due course was apprenticed to a respectable and well-established wholesale dealer in oil, whose place of business was near St Andrews Church, Holborn, London. If his parents had a fault it was in over-indulging their son, so that as he left childhood and entered his wilder years, he continued to believe that he could have anything he wanted and what he wanted he took. When thwarted of his desires, he would burst into a rage at those who opposed him. Predictably, his apprenticeship did not go smoothly, for he took liberties not appropriate to his humble position, but somehow all his little flights of folly were passed over as youthful high sprits. When the period of his apprenticeship was over, his proud parents set him up in business in a neat and well-furnished shop just outside Aldgate.

John Skinner was on his way to being a prosperous man. He married an attractive young woman from a good Essex family who brought with her a fortune of some 5,000 (about 475,000 today). The connections of both his own and his wifes families brought a great deal of business his way, and before long he was supplying the greater part of the county.

Money rolled in, but John Skinner believed that there was only one thing to do with money, and that was to spend it on his own personal pleasures. His three weaknesses were, predictably, drink, gambling and women, and he took to spending much of his time in brothels, neglecting both his wife and his business. On one occasion he was heard to declare that he had been at a bawdy-house for ten days successively during which time he had spent 60 to 70.

If he had considered his business at all, he must have thought that his servants would take care of it, but they soon took advantage of his frequent absences and made away with both his money and his goods. Skinner, more than other men, must have known that servants may be tempted by the indolence of their master, but when he sobered up enough to have a look at his books, he was very surprised to find a substantial deficiency. While complaining bitterly about the situation, he was too far gone in his life of debauchery and profligate spending to mend his ways.

Brightlingsea parish church, where John Skinner was baptised and buried. (Authors Collection)

His wife, powerless to do anything to improve the situation, and seeing her fortune being slowly consumed, hardly knew which way to turn. She may have felt ashamed of her position, or believed that it was something she should be able to deal with herself at any rate she was not able to bring herself to tell her parents what was happening. She was a woman of good education, knowledgeable about her husbands business, well-mannered and patient. When he was home she tried to advise him as best she could, but, as a contemporary observed he was one of those fine Gentlemen that could not bear to be talkd to by a Woman.

Skinner liked to live well, kept a brace of fine geldings and liveried servants, but when out and about taking his pleasures, seldom included his wife in the party, some demolishd Beau, Gamester, Sharper,... or Bawdy-house Keeper, were his constant companions; and he was so well known amongst those gentry, that he got the Name of Squire Skinner.

This situation could not go on indefinitely, and in a few years the inevitable happened, and Skinner found himself unable to pay his debts. A bankruptcy order was taken out against him, and it was found that he owed in total 10,000, though when the commission was finally closed he was able to pay his creditors 15s in the pound.

Having settled that little matter Skinner thought no more of the oil business, and indeed no more of his wife, who was brought to a state of utter destitution and was obliged to enter the parish workhouse. Though Skinner was to prosper in the future he was never to send his wife a single shilling for her support. He left London, and returned to his roots in Essex, where he took an inn at Romford, called the Kings Head. It was here he discovered that large profits could be obtained with very little work in the business of smuggling, and was immediately attracted to a way of life that seemed to be ideal for his tastes. Before long, he was one of the most notorious smugglers in the County of Essex.

Evading taxes has always been a popular pastime, and the imposition of high duties on desirable luxury goods will naturally attract the opportunist. In the eighteenth century, frequent wars prompted the government to raise finances by taxing imports such as Dutch gin, French brandy, tobacco and tea. At the same time, there were insufficient resources of men and ships to keep a watch on the coast. The result was a thriving industry of smuggling. The potential profits were high in the 1740s the duty on tea was 4

Next page