Copyright 2016 Linda Stratmann

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Regular by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press Ltd, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stratmann, Linda, author.

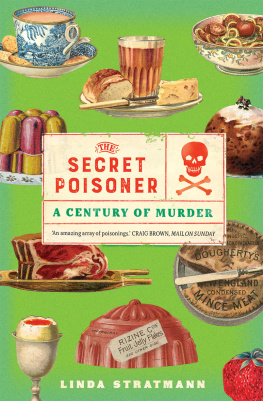

Title: The secret poisoner : a century of murder / Linda Stratmann.

Description: New Haven : Yale University Press, 2016.

LCCN 2015037508 | ISBN 9780300204735 (hardback)

LCSH: PoisonersHistory19th century. | MurderersHistory19th century. | BISAC: HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century. | TRUE CRIME / Murder / General. | SCIENCE / History. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Criminology.

Classification: LCC HV6553 .S775 2016 | DDC 364.152/30922dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037508

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to the Crime Writers Association, whose members include the very best of our fiction and non-fiction authors. The friendship and encouragement of fellow writers is beyond value.

De toutes les armes que le gnie de lhomme a inventes pour nuire son semblable, le poison est la plus lche; lempoisonneur est le plus mprisable des criminels.

(Of all the weapons that the genius of man has invented to harm his neighbour, poison is the most cowardly; the poisoner is the most contemptible of criminals.)

Contents

List of Illustrations

Authors Note

T his book is not and was never intended to be a simple compendium of poison murders, a collection of unconnected famous and infamous cases, neither does it claim to be an academic study; rather it tells a single unified story of a duel of wits and resources, the main thrust of which lasted approximately a century. Starting with the dawn of modern forensic toxicology and the first serious demands for control of poison sales in the second decade of the nineteenth century, I have chronicled the efforts of science and the law to combat what was then seen as a grave threat to society: the secret homicidal poisoner. It was a campaign in which progress was often fraught with contradictions. Even as chemists devised increasingly sophisticated methods to detect toxins in human remains, their researches isolated and refined new and powerful methods of murder that posed fresh challenges to the analyst. Repeated attempts by parliament to restrict the availability of poisons to the public were confounded and sometimes obstructed both by the need of the poor to have easy access to cheap medicine and the means of destroying vermin, and by the professional demands of doctors and pharmacists.

The nineteenth century also saw the rise of the specialist toxicologists and analytical chemists who were authorities on poisons, and whose antipathies and jealousies sometimes led to bitter and undignified wrangles that dented public confidence in medicine. When experts were called upon to testify at murder trials, there arose an uneasy interaction between the medical and legal professions, since the reputation of a witness could be made or destroyed in a single cross-examination.

I have illustrated the story by selecting those cases that show how poison murders stimulated both medical research and legal reform and influenced public opinion, and how increased restrictions on the availability of poison and improvements in methods of detection modified the methods of would-be murderers. I must apologise in advance, therefore, to anyone who was hoping that I would include a specific case and does not find it in these pages, also to those who feel that I have given a case that interests them far too little space. I, too, feel the loss of individual cases and detail, and I greatly regret that I was obliged to omit ones that, while fascinating in themselves, did not meet the brief or duplicated a point already made.

Those of you who have read my fiction will know that my lady detective does not spend her time wading boot-deep in unpleasant body fluids. I make no excuses for this it just doesnt feel right in those books. Here, however, in the world of the real, nothing will be delicately hidden. I would be doing the reader of medical and crime history a terrible disservice if I drew a discreet veil over the suffering of poison victims, both human and animal, or the unsavoury details of the subsequent post-mortem examinations. Consequently, many scenes were uncomfortable to write about, but, in a truthful book, this is necessary. In order to understand where we are now, we need to know where we have come from.

* * *

I would like to thank everyone who has helped me in the preparation of this book, most especially my editor at Yale University Press, Heather McCallum, who suggested an idea to which it was impossible for me to say no, the enormously helpful staff at the British Library and The National Archives, and author Kate Clarke, who has done heroic work digging out some obscure references. During my research, I enjoyed recreating some of the historical dishes that were the last meals of poison victims, and must thank my husband Gary, who courageously agreed to taste them.

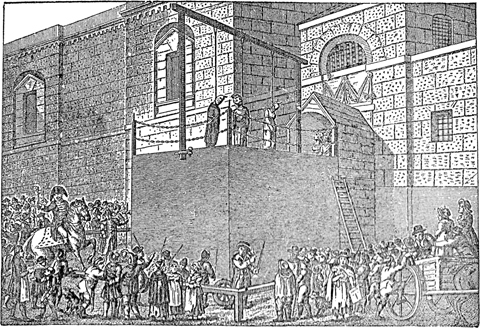

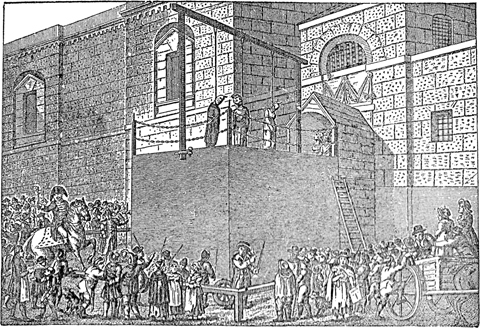

1 An execution outside Debtors Door, Newgate Prison.

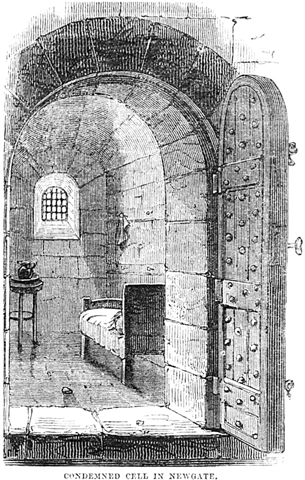

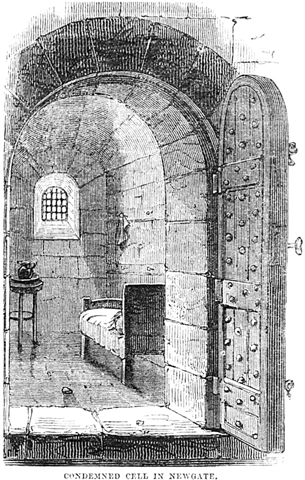

2 Interior of the condemned cell, Newgate Prison.

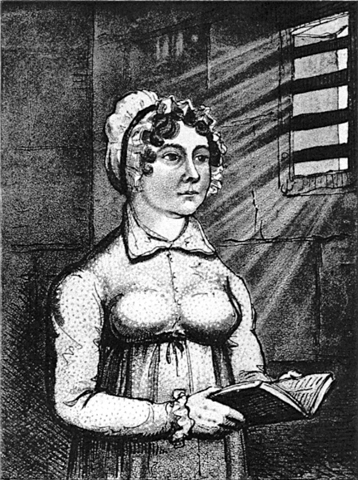

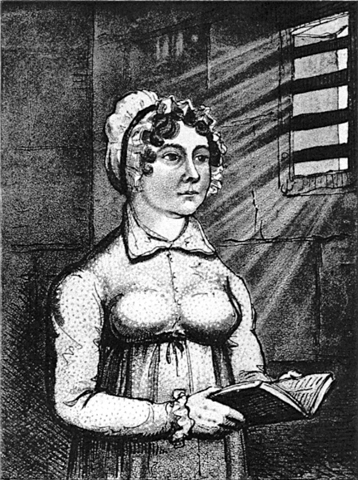

3 Eliza Fenning in the condemned cell, Newgate Prison.

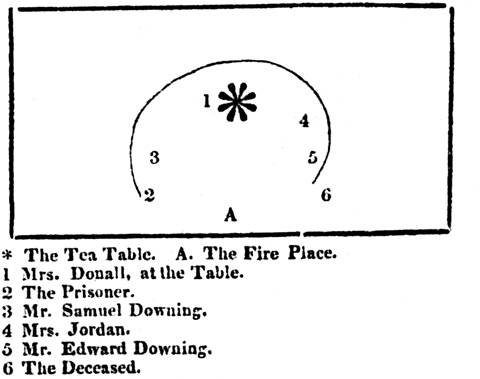

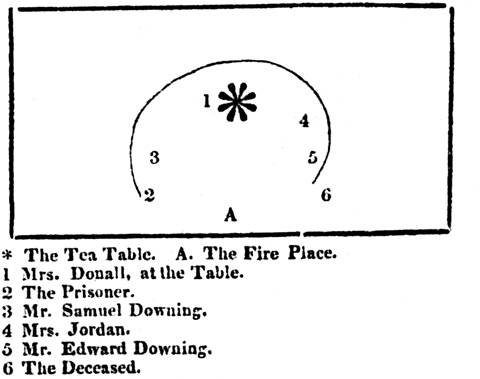

4 Contemporary sketch of the Donnall parlour showing the location of those present and Robert Sawle Donnall's unusual route around the table.

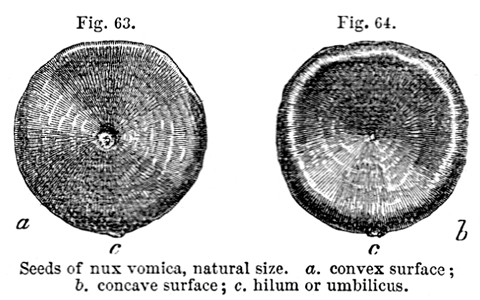

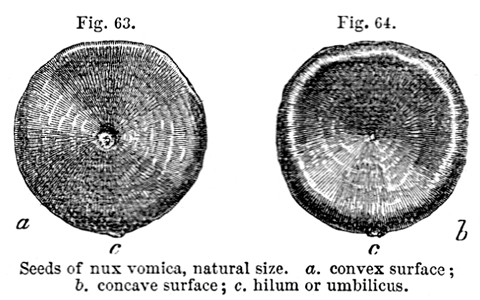

5 The nux vomica bean as illustrated in Taylor's Principles and Practice of Medical Jurisprudence. He described it as being the size of a shilling.

6 Mathieu Joseph Bonaventure Orfila in his robes as Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Paris.

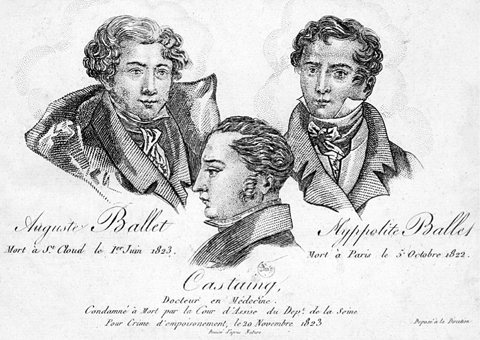

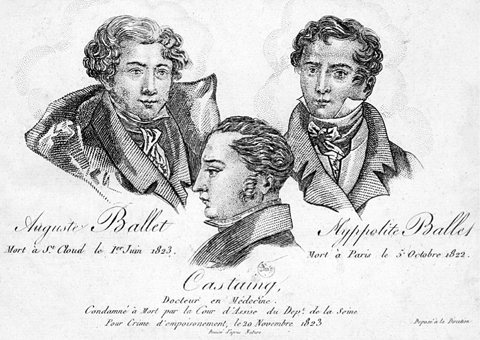

7 Edme Samuel Castaing and his victims, Auguste and Hippolyte Ballet.

Next page