Table of Contents

To Abba and Ammi, who would have felt proud today

Contents

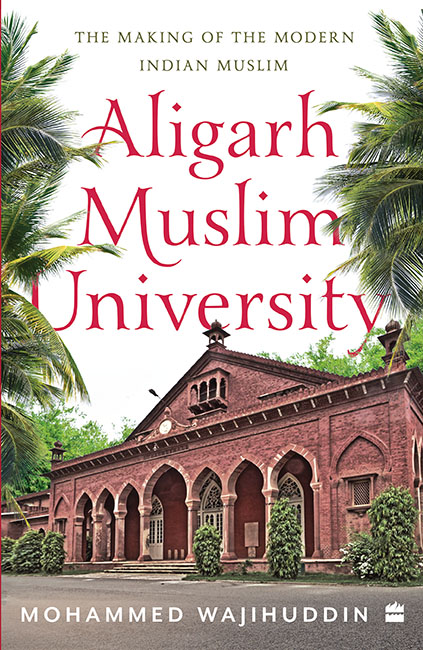

N OTED Urdu satirist and humourist Rasheed Ahmad Siddiqui (18921977) had a delightful pastime. Whenever he came across a well-mannered stranger, he would ask him whether he had ever been a student at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). It would please Siddiqui if the stranger turned out to be an AMU alumnus; it didnt surprise him at all that the stranger was so charming. But it saddened Siddiqui if the refined stranger told him that he had never studied at AMU. Siddiqui would feel sorry that such a nice person had been deprived of the nemat or boon of studying at AMU.

If Siddiqui were to return to the AMU campus today, he would be hugely disappointed. The Aligarh ethos that had moulded him and countless others, and which he longed to discover was behind any decent denizens he would meet, is gone. Yes, there are well-cut black sherwanis and tight-fitting churidar-pyjamas aplenty on display, especially on ceremonial occasions like the founder Sir Syed Ahmad Khans (18171898) birthday on 17 October, which is celebrated as Sir Syed Day by Aligs, or alumni of AMU, globally. A sherwani, churidar-pyjama and Turkish cap for men, and niqab or a hijab for women, were once the uniforms on the campus. M. Hashim Kidwai (19212017), who taught political science at AMU and served the university as provost of the residential halls and proctor of the university before he became a Rajya Sabha member (19841990), writes in his autobiography, The Life and Times of a Nationalist Muslim, that the sherwani and the Aligarh-cut pyjama began taking a backseat in the late 1950s. Until then, the male students wore sherwani and churidar even during summers. Things changed after the introduction of the bush shirt, and in the summer months the old uniform was discarded. Now, a minuscule minority dons the uniform that used to be the distinctive feature of the campus.

The dress code at AMU had entered the popular imagination, so much so that Hindi cinema had lapped it up. Remember the debonair Rajendra Kumar, smartly dressed in a white sherwani-churidar, crooning the romantic number Mere mehboob tujhe meri mohabbat ki kasam, mera khoya hua rangeen nazara dede (My beloved, please return my lost romantic view) from the 1963 film Mere Mehboob? The song features a scene where a sherwani-clad Rajendra Kumar unintentionally collides with the burqa-clad Sadhana, clutching a bunch of books to her chest. The books fall and both kneel down to pick them up. While doing so Kumar touches Sadhanas hands, a reason for the poet Shakeel Badayuni to describe the scene in the sugary, romantic strain Marmari haathon ko chchua tha maine (I had touched those marble-like hands).

That popular image of AMU boys and girls is fading. And the change is not merely sartorial. It is also in the way AMU is perceived. For decades in the last century, AMU remained an epicentre of Muslim politics, a nerve centre of Indian Muslims intellectual life. It made or marred the Muslim destiny like no other institution.

However, despite the noticeably painful downfall in the delightful tradition and culture Aligarh (the city of Aligarh and AMU became interchangeable over time) used to boast of, AMU does retain some of its original charms. Mara hathi bhi sawa lakh ka hota hai (even a dead elephant fetches Rs 1.25 lakh), goes a popular Hindi idiom, denoting the value of a once-giant entity. Despite its considerably reduced utilitarian value for the communityafter all, one university cannot fulfil the educational needs of a twenty-crore-strong community in the countryAMU remains a centre of intellectual life for Indian Muslims. As Akhtarul Wasey, professor emeritus at Jamia Millia Islamia (JMI), Delhi, and president of Maulana Azad University, Jodhpur, puts it: It is the largest hub of intellectuals in the Muslim world. Nowhere in the world you will find so many educated Muslim minds concentrated at one place. Dr Zakir Hussain (18971969), AMU alumnus, its former vice chancellor (VC) (19481956) and later President of India, summed up AMUs roadmap thus: The way Aligarh participates in various walks of national life will determine the place of Muslims in Indian national life. The way India conducts itself towards Aligarh will largely, yes, will largely, determine the form that our national life will acquire in the future.

It is against this backdrop that Prime Minister Narendra Modis virtual address to the AMU at its centenary celebrations on 22 December 2020 commanded importance. (The Madrasatul Uloom Musalmanan-e-Hind, founded in 1875 by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, graduated to the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental [MAO] College in 1877, further metamorphosing into AMU in 1920.) It has been a remarkable journey of a century since the Aligarh Muslim University Act was passed on 1 December 1920 and the universitys inauguration on 17 December 1920. In that memorable televised speech, Modi killed two birds with one stone. He silenced, albeit temporarily, the section in the Sangh Parivar that has always viewed AMU with suspicion and seen it as a bastion of Muslim separatism and an incubator of fifth columnists. However short-lived people think it may be, Modis assurance to the AMU community and its vast circle of sympathizers was that the ruling dispensation in India has stopped seeing AMU with a jaundiced eye. He left nothing to the imagination when, in his characteristically convincing style, he declared: We see a mini-India [at AMU] among different departments, dozens of hostels, thousands of teachers and professors. The diversity which we see here is not only the strength of this university but also of the entire nation. [The] History of education attached to AMU buildings is Indias valuable heritage.

In May 2018, AMU was rocked by a controversy over a portrait of Pakistan founder Mohammad Ali Jinnah that had been hanging in the AMU Students Union Hall since 1938. The Bharatiya Janata Partys Aligarh Member of Parliament Satish Gautam sent a letter to AMU Vice Chancellor Dr Tariq Mansoor demanding the removal of Jinnahs portrait from the campus. Just a few days earlier, some students had asked for an RSS shakha to be set up at the AMU campus. On 2 May 2018, around two dozen youths affiliated to right-wing outfits stormed the varsity, protesting against the Jinnah portrait. Several students were injured when they clashed with police outside the universitys main gate, Bab-e-Syed. Student leaders alleged that the right-wing activists wanted to hurt former vice president, former VC and AMU alumnus M. Hamid Ansari, who was on the campus at the time for a programme. Ansari was scheduled to be awarded the students unions honorary life membership, an honour the students had bestowed on Jinnah in 1938. Jinnahs portrait has been hanging on the union halls wall since then. But the first person to decorate this wall of fame had been Mahatma Gandhi. The AMU boys had felicitated him in 1920, eighteen years before Jinnah got the same honour.

On 30 May 1939, Jinnah wrote his will, according to which all his properties were to be divided into three parts. One part was to be bequeathed to AMU, one part to Islamic College, Peshawar, and one part to Sindh Madrassa, Karachi. Through this will, Aligarh Muslim University will be within its rights to demand its share in the Jinnah House in Mumbai. But AMU never did. There are many unkind, unpleasant things in history and tradition. Do we go on demolishing all these unpleasant things? That portrait is also part of a tradition, argues Shafey Kidwani, senior professor of mass communications at AMU.