M Y thanks go to Sarah Bush, Ken Baker, Peter Barker, Pat Bricheno, David Brown, Marie Brown, Graham Burgess, the Butt family, Liz Eldred, Colette and Joe Entwisle, Kate Entwisle, Mike Hibbett, Lisa and Steve Hockley, Marc Hollingworth, Jack Kemp, Mr N. Maddams, Alan Murdie, Jeanne Powell, Su Purcell, Tracey Sneddon, Val White, Claudia Wiggins, Wally Wright, and Steve Wood.

I also thank the scores of other people working in public houses, restaurants, offices and shops who gave me information enabling me to write this book. The honest, reliable and frank reports were given to me by sincere, ordinary people who had experienced, or knew of, the ghostly occurrences recorded here. Some of those mentioned above are also thanked for their help on computer matters.

I would also like to thank Matilda Richards and Emily Locke of The History Press for their help and patience.

All photographs are from the authors collection unless otherwise stated. Illustrations are by the author. (The Shrieking Woman illustration on page 55 is an idea taken from Nemesis of Neglect by John Tenniel for Punch magazine, 1888.)

CONTENTS

I N 1961 it was estimated there were some 10,000 reputedly haunted places in Great Britain, though further enquiries frequently revealed many of these to be regrettably inactive.

Some towns and cities, including York, Edinburgh, Cambridge, Farnborough and Cheltenham, seem to routinely generate many reports of ghosts and hauntings. Certain famous locations, such as the Tower of London, Hampton Court Palace, Glamis Castle in Scotland, Berry Pomeroy Castle in Devon and Newstead Abbey in Nottinghamshire have all appeared in ghostly guides and gazetteers many times since the Victorian era.

Yet reports of ghosts and haunting in the UK are by no means evenly distributed. Often stories seem to be concentrated in a relatively small pocket, whilst large swathes of the UK seem to be almost wholly bereft of ghost sightings. Curiously, although a town with a long history, Bishops Stortford appears to be one such location, omitted from all major ghost-hunting guidebooks and gazetteers covering Britain. Even in Hertfordshire folklore, the ghosts of Bishops Stortford seem to be conspicuously absent, and the most diligent searches of county libraries and newspapers have turned up but a small handful of reports at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Some people have speculated about certain areas being window areas, more prone to being haunted than others. However, the relative absence of ghost stories in particular places may simply reflect the absence of anyone prepared to record such accounts.

That there were ghost stories awaiting discovery in Bishops Stortford I was long certain. As a child I had been told by a relative of his own experience of seeing the ghost of a woman in his house in the town, early one morning in 1948 or 1949. He was sure it was the ghost of the previous owner, who had committed suicide by gassing herself in the kitchen. This apparition only appeared once or twice, and was treated simply as a matter of fact, rather than as a cause for concern.

With Haunted Bishops Stortford Jenni Kemp has produced a most welcome book demonstrating that such local ghostly experiences are by no means unique. In collecting and publishing these accounts for the first time, she restores a long-overdue balance to the study of haunted places around Hertfordshire, showing that as a town Bishops Stortford merits a major entry on any map of haunted Britain. Her intriguing and fascinating book provides many new leads for ghost investigators and brings a whole new dimension to the town for visitors and tourists. I am sure it will also set many local readers searching through its contents, fearing the worst about some of the places they know and frequent.

Alan Murdie

Chairman, The Ghost Club

2015

U SUALLY a town is named after a river that runs through it or nearby, but in this case the River Stort was named after the town. Esterteford was a Saxon manor mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. The name may derive from Steorta, a family that ruled here. In 1060 the manor was sold to the Bishop of London by Edith the Fair, mistress of King Harold, and became known as Bishops Esterteford hence Bishops Stortford.

The manor was important to the Romans as it was on a route from St Albans to Colchester. Their encampment was in the town meads area. After the fall of the Roman Empire the town was deserted then the Saxons came.

The Normans were responsible for building the castle known now as Waytemore Castle mound, as only the mound remains in Castle Gardens. In 1208 King John was in dispute with the Pope. He captured the castle from the bishop and had the castle destroyed. In 1214 he was ordered to have it rebuilt at his own cost.

Stortford succumbed to plague three times: the Bubonic Plague in 1349 (13461353), which wiped out half the towns population, the Black Death in 1582/1583, which it took sixty lives, and the Great Plague of London in 1665, which spread through the Stort Valley and the town, wiping out half the population.

Maze Green Road was once named Pest House Lane. This probably originated from the pesthouse that was situated at the top of the road outside the town boundary. In medieval times every town had its mazel or leper house, and the green at the top of the road may have been the site of the mazel hence Maze Green Road.

The sick of Bishops Stortford were not put in isolation until the pesthouse was built.

Bishops Stortford has been a market town since medieval times. The market and fairs were held outside the church and further up Windhill above flood level. By 1801 the town had flourished, and the corn exchange was established, the main business being malting. The river was used to convey malt supplies to Londons breweries. The river canal was later used to ferry timber, coal and other goods.

There was a weekly cattle market, which took place at Northgate End and was described in 1767 as the finest in England. The market was discontinued in the 1960s.

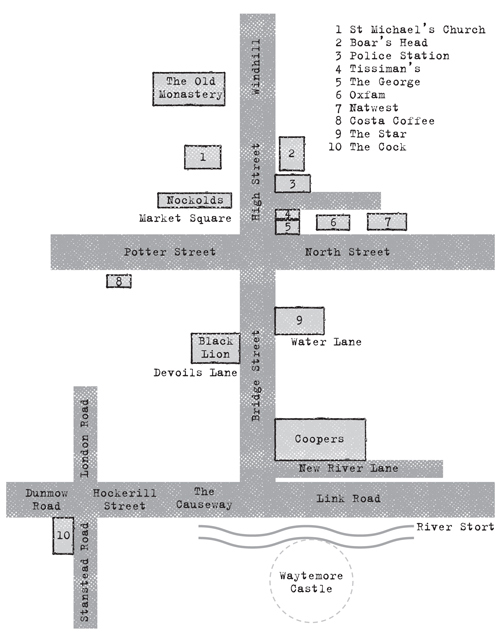

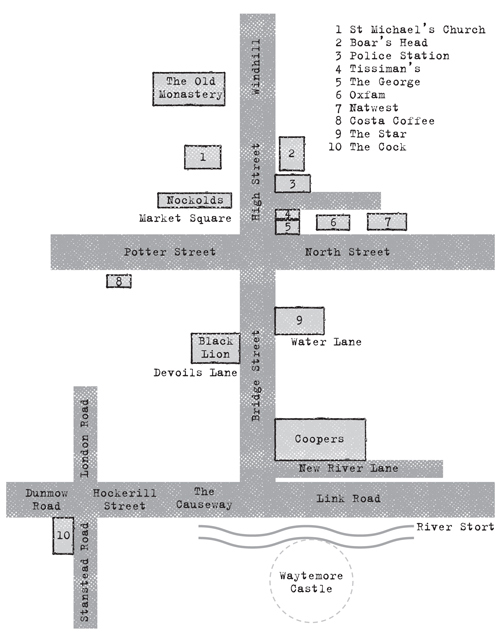

Not to Scale

During the Civil War the people of Stortford supported Cromwells men, except Lord Capel of Hadham Hall, a noted Royalist. Cromwells men were billeted at St Michaels church and the Boars Head, opposite. Richard Whittington (Dick Whittington (13581423), Lord Mayor of London) was Lord of the Manor of Thorley. A school and road are named after him on the Thorley estate.

In the eighteenth century, Stortford was a thriving hub on the route from London to Cambridge. Four inns stood at the Hockerill crossroads. King Charles II, his mistress Nell Gwynne, Samuel Pepys the diarist, and the highwayman Dick Turpin all stayed at these hostelries. Now only one of these old inns survives the Cock Inn, situated on the corner of Stansted Road and Dunmow Road. The George in North Street was a terminus for the stagecoach that ran daily to The Bull in Aldgate, London. Due to the flow of travellers more inns appeared. Although the birth of the railway saw the death of the stagecoach and the wane of such hostelries, some of these ancient inns are still standing and providing sustenance to the populace today.

Next page