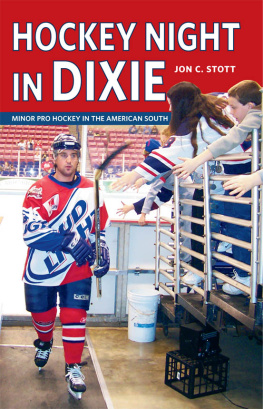

Research for this book required many dozens of interviews by telephone, fax and in person. To all those mentioned in the book who helped with anecdotes, observations, bitchy opinions and cheerful recounting of personal experiences alikeTed Hough, Frank Selke, George Retzlaff, Gerald Renaud, Harry Neale, Bud Turner, Roger Mallyon, Ward Cornell, and Ralph Mellanby among themmy thanks. Special thanks also to Dick Irvin for permission to use a passage from his own book, Now Back to You, Dick. But the biggest stroke of luck for me was that Bob Gordon, having bade farewell to Hockey Night in Canada after 33 years of faithful service, agreed to head up the overall research. He did a magnificent job. If there are errors or omissions, Im the culprit.

In a nation where one of the principal preoccupations is hockey talk, with gossip, prejudices, truth and untruth inextricably mixed, hockey broadcastersThe Boys of Saturday Nightknow more about the pro game, past, present and future, than most. Its not only what they see and hear covering games in 21 cities for more than nine months of the year. In the average week during the season a professional broadcaster with a home satellite has a choice of watching something close to three dozen NHL games. When Don Cherry gets off a zinger about this player or that, this team or that, you can be sure it is not hearsay. Hes seen it. Hell stay up until two in the morning or later to get the end of a game on the Pacific coast, and if that means he misses some other game he wants to see, he often can get it on a repeat that night or the next morning. Besides Hockey Night games on the CBC, on the Global network, or The Sports Network on cable, anyone with a satellite dish and the appropriate de-scrambler, if necessary, can get anything on several U.S. all-sports networks and even some that are televised in only one local market.

To take one representative period, from March 24 to March 31, 1990, there were 41 NHL games, almost all available somewhere on satellite. When the playoffs started April 4, there was hockey on television almost every night for six weeks.

In covering all that hockey, a special relationship develops between at least some of the broadcasters and the hockey players, coaches, managers, trainers and other personnel. Theyre all in the same game, one way or another. When Harry Neale was fired as coach of Detroit Red Wings in 1986, two of the Sutter brothers skated up the next time they saw him and, calling him Mr. Neale, said they were sorry. Most players know what it is to be fired, or traded, or sent down, and can relate to someone else it has happened to.

And when broadcast crews come into a rink several hours before game time, its to a sort of private hockey world, with a limited number of initiates. To follow one specific pair, Bob Cole and Harry Neale: One February night when Pittsburgh was in Toronto they went straight from the production meeting ending at around six and headed out through the all-but-empty rink toward the broadcast booth to go over their notes on the people theyd be watching; but also they picked up a few impressions along the way, seeing things the fans didnt see. That night, for instance, all-star Pittsburgh defenseman Paul Coffey was taking his ease dressed in undershirt, shorts and not much else in a gold seat at Maple Leaf Gardens, chatting with Leaf assistant coach Garry Lariviere; theyd been teammates with Edmonton a few years earlier. Neale stopped and got into the conversation. Back near the players benches Ron MacLean was talking to Wendel Clark. In the open area outside the visiting teams dressing room under the stands, Randy Hillier and Mario Lemieuxstill healthy thenand others, half-dressed, were customizing their sticks, while a few feet away facing the necessary hot lights, visiting broadcaster Jiggs MacDonald was taping his own opening. Players, broadcasters and all the rest exchanged opinions, gossip and real news. Trainers who have been around forever were doing their pregame tasks.

Coaches have been fired, players traded, promoted, sent down. A chance conversation might make an item on the broadcast that night or another night; the participants are in a little world of their own, before a game, after a game, between games, while riding the same aircraft, staying sometimes in the same hotels. They know, and have critical or kindly opinions about, this official or that. It all hangs out.

Even for broadcasters who travel across the continent its a tight little ship, much more so than the relationship, say, between active coaches in the league. Harry Neale and Scotty Bowman live not far from one another in East Amherst, a suburb of Buffalo. They do the same job for Hockey Night, providing commentary and analysis, Neale a regular in Toronto and Bowman in Montreal, working the same game only sometimes when Montreal plays Toronto and the crews are mixed. When they were rival coaches in the NHL, they would, of course, seldom have occasion to speak to each other. Now, they are colleagues, able to share a familiarity not possible before.

Were good friends now, Neale says, but when you coach against Scotty, youre the enemy. Theres no friends. He was always one of those guys who was looking for an edge somehow, and he didnt care whether it offended youthat was the game he had to win tonight.

Now that both are rated among the best color men in the game, they rarely work in the same place at the same time, but talk in person or by phone two or three times a week. Maybe Bowman is coming up to a game involving a team whose game Neale had done a few days earlier. Or vice versa. In such cases theyll compare notes on everything useful to broadcastershow certain individuals are playing, how the team is playing, balance, weaknesses, strengths. Its all part of the preparation by two men, former coaches, each with pride in doing well whatever they doBowman with his Stanley Cups in Montreal, Neale, rarely having had the same quality of gunners, once coming close with Vancouver. Long in hockey, new in friendship, from time to time they see sides of one another that they didnt know existed.

Ill never forget one time last year [spring 1989], Neale relates. Scotty had been out west, including Calgary and Edmonton, about four games in six nights, and you usually get good games when you go out west, and were chatting and he says, You know, Harry, Calgarys not going to wintheyre not going to win the cup.

I say, Well, what about Edmonton?

No. Not this year.

Well, what about Philly?

No.

Finally wed gone through about five teams that hes saying havent got a chance and I say, Scotty, at the end of May theyre going to give that cup to somebody, whether you like it or not.

That year, Calgary proved Scotty wrong. Neale did not rub it in.

So, witty or serious, salty or tame, the mix is there, bringing us night after night for two-thirds of the year what we want to see and hear: who won, who scored, the ever changing state of the game.

Star players, coaches, managers, owners, referees and just about everyone else in the game have had books written about them. This one is about the broadcasters, and the men and women who work out of microphone and camera range, to deliver hockey to air, on time, excitingly, rousingly, sometimes even grammatically. The Boys of Saturday Night.