Up Fairview Road running southwest from downtown Oliver, British Columbia, till you got to where the mining town of Fairview used to be, then a right turn off the road into a miniature valley between hillocks, I guess youd call them, is where you would find a small irregular pond with some bends and narrow spots, and sagebrush islands or sumac bushes growing up from the middle. If it was one of those winters with snow and ice, thats where you would find a shallow frozen pond with snow on top of the ice, and wind tucking drifts of snow against those brittle bushes. This is where kids whose families had moved from the prairies to the South Okanagan would hike to play hockey.

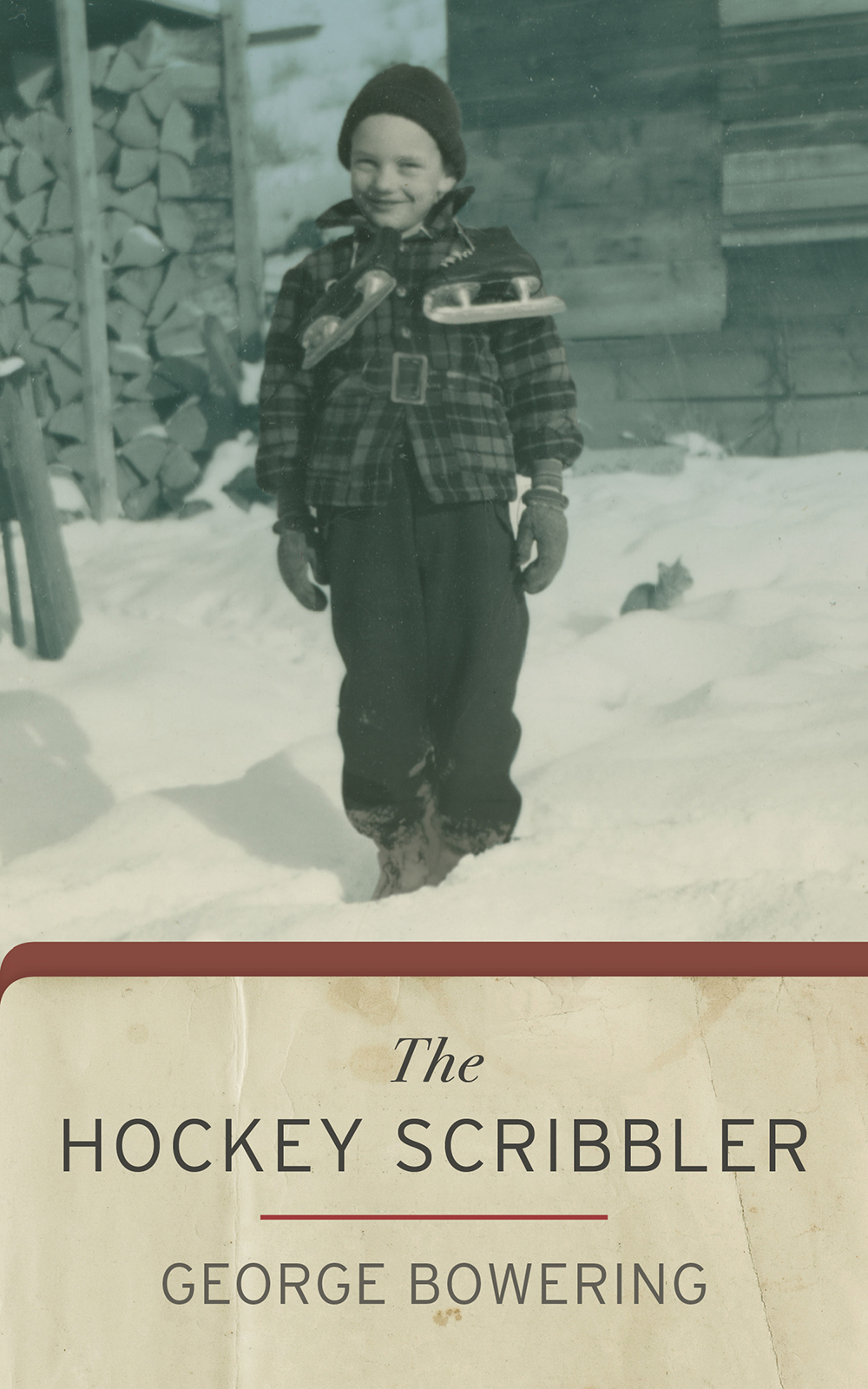

They would get up very early on a Saturday, the way kids will do, and hike up there with shovels and skates and sticks. It would take them till early in the afternoon to get all the new snow off the ice, and then they would drop shovels, pick up sticks and play pond hockey for two hours. Then they would trade skates for boots and get a good downhill start because it would be dark by four oclock.

These were kids who used to skate in their own back yards in Saskatchewan. They had Russian names and German names and seemingly boundless energy. After church on Sunday they would be back up at the pond, and if it hadnt snowed overnight, they had a whole afternoon of skating hard before going home and doing their chores in the dark.

These kids were really good. They had been playing hockey since getting their first second-hand skates around age four. They would use a bush as a third defenceman. They did not have all that Canadian Tire equipment you see city kids with now, the lightweight goal net and all that. They had taped-up wooden sticks with which they zoomed in on a goal that was simply made of a few jackets with space between them. Any puck that got by the goaltender had to be less than four feet in the air.

I never played with these guys. Taking on a kid from Saskatchewan at hockey would be like trying to out-swim a seal. But I did help with the snow, and I did mark down the goals and assists in a Hilroy. I would have kept time, but really, there was no time up there.

One of those Saskatchewan kids was Tom Moojalsky. He and his brother Sam and sister Marjorie and the youngest kid, who went by the name Baby, used to live at Veregin, outside Kamsack, Saskatchewan, two towns best known as the site of several poems by John Newlove. Newlove, too, moved from eastern Saskatchewan to British Columbia, and prairie roads and rivers haunted his poems. He was a rainy window intellectual, but he was also a hockey fan. He often threatened to shoot or stab anyone who got between him and the television screen when Hockey Night in Canada was on.

I dont remember any hockey poems by John Newlove, though he did not shy away from violence of other sorts. And even his saddest poems about the prairie are immaculately beautiful, such as this little one called Return Train:

A low, empty-

looking, unpainted house;

back of it, the corn

blighted, the tractor

abandoned.

Thats from a 1986 book called The Night the Dog Smiled.

The Moojalsky family arrived in town when I was in elementary school. In grade five we all had to make a presentation in front of the whole class. I cant remember what mine was about, but I do remember that Tom Moojalsky explained the rules of ice hockey. He really knew his stuff, too. Remember, this was in a small Canadian town a long way from the nearest hockey rink. So I dont know how interesting this was for the girls in the class, Sylvia MacIntosh, for example, or Joan Roberts, but I dont think that I was the only boy that learned something the day Tom Moojalsky told us what the blue line was for, and what an offside looked like.

I mean we all heard these words on the radio on Saturday nights, but when Foster Hewitt mentioned that Gaye Stewart had fired a shot from the point, I for one did not know what the point looked like.

Of course in that room in the two-storey schoolhouse at the foot of a brown mountain there were other pupils who had lived on farms on the prairie, and they knew what a hockey rink looked like. Kids such as I had seen lots of black-and-white photographs of hockey games. But we did not know what the ice smelled like, or what bodychecking sounded like. I think I remember that Tom gave that presentation again in grade six. Why not? Thats how you learn things.

If I remember correctly all these years later, Tom and Sam Moojalsky were two of the boys skating around sagebrush up that hill in the disappearing light. I wish that I could have seen them on the sheet of ice that Tom described in his presentation.

Living as we did 15 miles from the United States and a long way from Ontario, we did not have many things in our quotidian lives to keep us Canadian. Two things did that: the Star Weekly and Imperial Oils Hockey Night in Canada. The Star Weekly was apparently a weekend paper back in the shroud that was Toronto, but we got it by mail on the next Thursday. It seemed to be a staple of just about every household, though I do remember that some immigrants from the prairies got a similar weekly from Winnipeg. The comics section had The Phantom, otherwise unavailable to an Okanagan boy.

The Star Weekly came in sections. There was a rotogravure that often had pictures of Easter in Toronto or Christmas in Toronto or Halloween in Toronto. I always snaffled the Phantomless coloured comics section, and during the week my father would read the condensed novel, which was often the most recent Erle Stanley Gardner case. I dont remember my mothers choice or my sisters. I would not read the condensed novel, because I had already decided that you shouldnt read condensed things. I got that idea from the assurance in drugstore paperback westerns that the Pocket Book or Bantam Book in your hand was complete and unexpurgated.

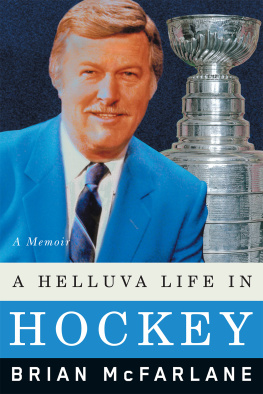

Hockey Night in Canada was the reason that there was no vehicular or foot traffic along the roads around Oliver (or Osoyoos, or Okanagan Falls, etc.) on early Saturday evenings during the months between October and April. Thanks to the high radio aerials at Watrous, Saskatchewan, or if the weather was all right, CBCs Trail, B.C., station, we could tune in at six p.m. and hear Foster Hewitt say, Hello, Canada, and hockey fans in the United States and Newfoundland, there are two minutes remaining in the first period and there is no score between the Boston Bruins and the Toronto Maple Leafs.

No, we never got to listen to the whole first period. They didnt in Toronto, either. Maybe they were worried that Maple Leaf Gardens wouldnt fill up. We did not get to listen to the Montreal Canadiens games, either. These were broadcast on CBCs French network. Maybe once a season the Canadiens would play a Saturday night in Toronto, and the excitement would go up. This was especially true in our house, because my father was, for some inexplicable reason, a Canadiens fan, and I was a true blue Maple Leafs supporter.

Heres how true a Maple Leafs supporter could be in the iceless Okanagan Valley thousands of miles from Maple Leaf Gardens, where Foster Hewitt described games from his perch high in the gondola: I was a member of the kids fan club. I saved my allowance and other income and sent away for their stuff. I had a Leafs pennant, glossy photographs with reproduced signatures of men such as Bill Ezinicki and Vic Lynn, an adjustable ring (oh, I wish I still had that), and an impressive certificate that said it or I was officially affiliated with the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey club. I didnt have a firm hold on that word. When I told my father that I and my stuff were officially afflicted with the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey club, he laughed and laughed as only a Habs fan can.