Dedication

To Joan, my partner in this long parade:

Seventy years after we met, 65 since we married, she still has boundless energy. Seven years ago, at 81, she joined our daughter Brenda and her husband Kevin at Burning Man in the Nevada desert, where 60,000 people gather each year for a monster festival. She braved frigid nights and fierce dust storms, sleeping in a pup tent. But she rose each morning to teach fitness classes to kids in their 30s, 40s, and 50s. Not bad for a great-grandmother of three, one who can still drive a golf ball, has popped a hole-in-one, has garden plants taller than Jack who grows beanstalks, and who plans to live until shes at least 116.

In memoriamTed Lindsay:

Like millions of others, I miss you, Ted. We worked together on the NBC telecasts with Tim Ryan for three seasons in the 70s, and they were the best years of my career. Tims, too. Such an honour for both of us to be in your company. You had a million friends, and you chose to become special friends to us. Lifelong friends. You led us on the ice, too, as captain of our NBC hockey team, which played media clubs all around the NHL before our Game of the Week. What a thrill it was to be your linemate and watch you toy with some of the eager media wannabes who scrambled over the boards to face you, desperately hoping to stop youand failing. But they are able to brag, I played against Ted Lindsay!

Ted, you had all the class of a Jean Beliveaua man you greatly admired. And for the kindness and generosity you displayed to one and all throughout your life, you are revered. Sometimes the path you followed to achieve hockey greatness was daunting, but you never faltered. You stood up to the vilification of greedy, self-interested managers and owners, because the game you loved needed change. You moved the game forwardat great personal cost. You are my hero and my friend. You are the only former NHLer I know who still had a locker in the Detroit dressing room when you were 90. It may be difficult for a restless rebel like yourself to grant my wish, but please: if you are in hockey heaven somewhere, be friends with old opponents, be forgiving of referees, managers, and owners who made you bristle. Ted, my friend, please rest in well-earned peace

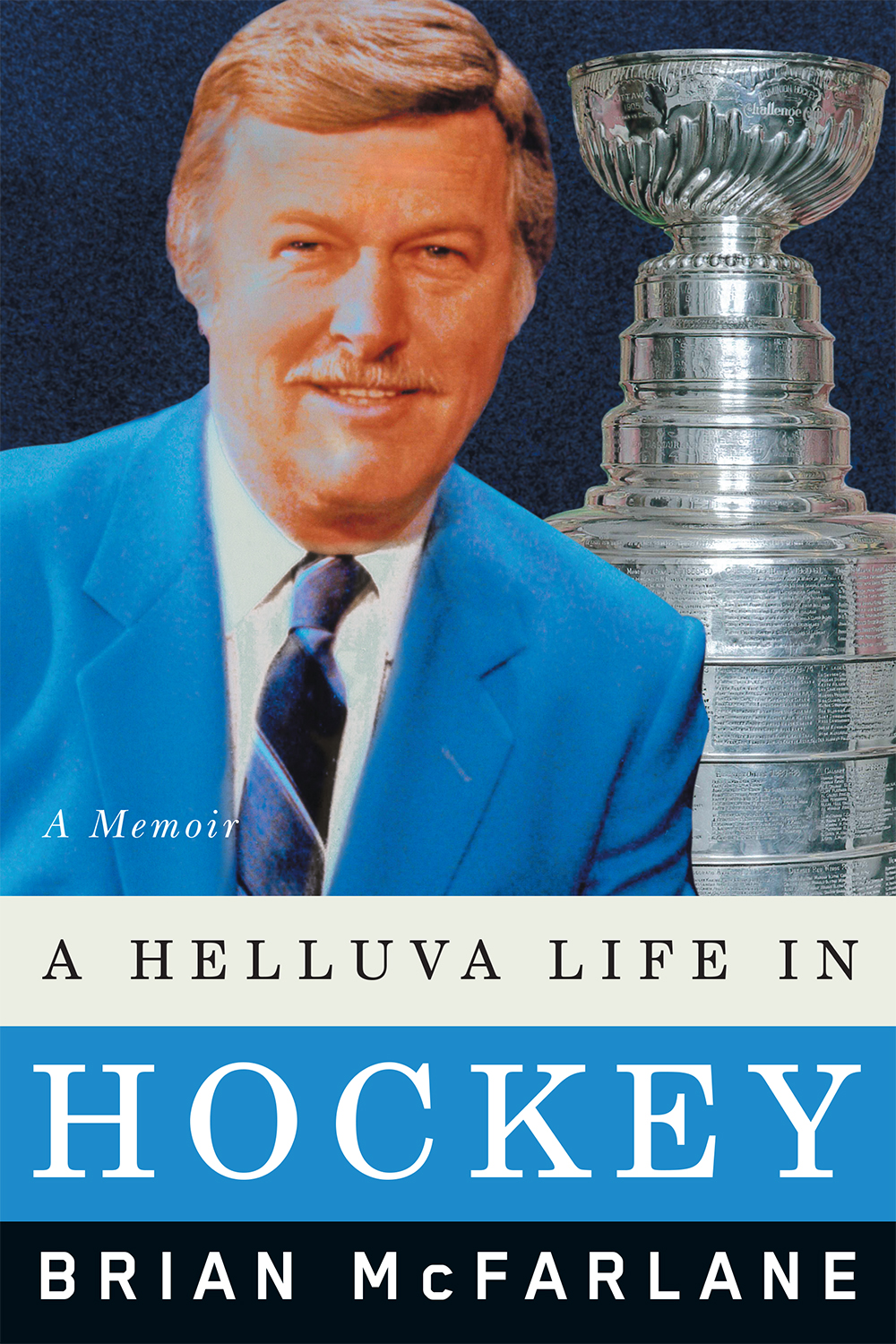

Introduction

When I joined Hockey Night in Canada as a colour commentator in the mid-1960sbeginning a 25-year association with the famous telecastthe National Hockey League (NHL) was a six-team league. Everywhere across the land, Saturday night was reserved for watching hockey. The Hockey Night in Canada theme song was as familiar to most of us as the national anthem.

When I started working high up in the famous gondola at Maple Leaf Gardens, with legendary play-by-play men Foster and Bill Hewitt, colour television was a highly anticipated marvel a year or two in the future. Each NHL club carried just one goalie on its roster, which meant the seventh-best goalie in the world toiled in some minor league. A Hall of Famer like Johnny Bower spent 10 years away from the show. If a regular goalie was injured or ill, the team trainer or a junior netminder was hurriedly recruited to take his place. I found it farcical. A porous substitute in a single game could mean the difference between a team making the playoffs and losing out. It could bring a player a scoring title he didnt really deserve, because hed collected four or five points against a floundering amateur. But nobody seemed to care. The team owners were frugal. Why hire a full-time backup if nobody complained, if nobody ordered them to? The Chicago Blackhawks once put a stuffed dummy in goal for practice sessions. How would the fans have reacted if theyd propped him up in goal in a real game? Or called for volunteers from the stands to don the pads in an emergency? Thats an ideal segue to Moe Robertss story. Roberts was a Blackhawks trainer in the early 50s, following a long pro career as a goalie, mostly in the American Hockey League (AHL), but with a handful of NHL starts.

Then on November 25, 1951, Roberts had to finish an NHL game for the injured Harry Lumley, the Blackhawks starter. Although Roberts didnt yield a goal, his Hawks still fell to Detroit by a 52 score. At 45, Roberts, in his final game, became the oldest player ever to play in an NHL game, a record he held until broken by Gordie Howe in 1979 and also passed by Chris Chelios. He remains the oldest goaltenderand perhaps the most obscure goalieto ply his trade in an NHL tilt. Johnny Bower, at 45, a few months younger than Roberts, is the oldest full-time goalie to play in the NHL.

No goalie masks, one or two helmets back then. Well, maybe one or two. No names on jerseys. No player agents. No million-dollar salaries. No Europeans or college players. I recall only one American, Tommy Williams from the U. S Olympic champs at Squaw Valley, California, in 1960. Olympians were all lowly amateurshardly worth a scouts time.

There was talk of NHL expansion, but it was mostly talk.

A proposal to start a new league, one to rival the NHL? Laughable. Who would dare? President Clarence Campbell pooh-poohed that idea. Itll never happen, he stated.

The Russians? Forget the Russians.

Saturday night was hockey night. It was a tradition that began with Foster Hewitt on radio in the 30s. Then, from 1952 on, all across Canada families gathered in their living rooms to watch the games on televisionon the CBC. But not all of the game. They were deprived of mostif not allof the first period. Showing the full game might hurt ticket sales, the big shots wrongly figured.

Youngsters were seldom allowed to watch a complete game before being ushered off to bed. Many would sneak to the head of the stairwell and listen to Foster Hewitts voice from there. Wives made trips to the kitchen, where they gossiped with other wives and prepared snacks for the male fans, who smoked their cigars and cigarettesand drank their beer or their rye and gingers close to their black-and-white TV sets. Small sets, many with rabbit ears. You dont know about rabbit ears? Ask Grampa. No, better not. Hes a kidder. Hell tell you they were real rabbit ears.

Most of my telecast teammatesFoster and Bill Hewitt, Jack Dennett, Ward Cornell, and Danny Gallivanwere already household names, as familiar as the powder-blue jackets we all began to wear on TV. Fosters three-star selections were as eagerly awaited as the national news.

Some viewers thought Murray Westgate, the actor who pitched commercials for Imperial Oil while wearing a cap and an Esso patch on his uniform, actually owned a service station.

Westgate and I were there when the NHL doubled in size in 1967, the year the Leafs won their last Stanley Cup. My wife and I crashed the victory party at Stafford Smythes house. Drank from the Stanley Cup for the first and only time. I wonder how many others who were at the game that night are still around? Not many, Ill bet. If my wife and I live long enough, we may be the only two people who actually saw the Leafs win the Cup. Bill Hewitt and I called that game, not thinking for a second it would be the Leafs final Cup win in the century. And they havent come close in this century.

I was among a group of broadcasting pioneers in a televised world of skill on skates, bench-clearing brawls, one-man coaching staffs, iron-fisted owners, and a mere two playoff rounds to decide the Stanley Cup champions.