The City Within

Edited by

JOSEPH CAMPANA

HarperCollins Publishers India

This book is dedicated to the people who have made Dharavi their home. May they continue to live there on their own terms.

CONTENTS

V inod Shetty, the head of ACORN India, an NGO that provides various services for the waste collectors and sorters in Dharavis recycling district, came up with the idea for this book in February of 2009. At the time, all eyes were on Dharavior so it seemed. Slumdog Millionaire had just won numerous Golden Globe and BAFTA awards, and was primed to win an academy award for best picture. Articles appeared daily, both excoriating and defending the film, in national and international publications. The term poverty porn was coined to describe Boyles portrayal of slum life and viewers fascination with what they saw.

Shetty thought the international attention had created an audience that would listen to the people of Dharavi speak about their families, their work, and what they felt about the changes that would be coming if the Dharavi Redevelopment Plan was implemented. He asked me to find journalists who would go into Dharavi and tell the stories of the people and the place. The writers would do this for free. You can have this book ready in a month, he said. No problem, I told him.

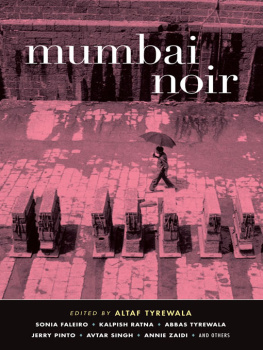

There were, however, two problems. First, I knew exactly zero journalists in town. Second, I was not confident that anyone would have the time to participate. It was worth a shot, though. The first four people I contacted enthusiastically endorsed the book, told me it was an important project, and politely declined. Some politely declined numerous times. Then Dilip DSouza and Sonia Faleiro endorsed the projectand agreed to provide material. Things began falling into place. Then in November 2010, HarperCollins came into the picture. Nearly four years laterafter commissioning, selecting, and editing the articleswe finally have a book.

At the start, I conceived the book as an argument against the Dharavi Redevelopment Plan. Approved in 2004, the DRP amounted to an agreement between the Government of Maharashtra, managing planner Mukesh Mehta, and several consortia of builders to divide Dharavi into sectors, modernize its infrastructure, bulldoze the many hutments where people lived and worked, reinstall the residents in high-rises consisting of 300 sq. ft apartments, and construct upscale buildings on the freed-up space to be used as homes and offices by the citys rising middle class. In Mehtas words, Dharavi would be transformed into an integrated township, complete with schools, hospitals, green spaces and all the amenities anyone could want. Potters, jewellery makers, leather workers and garment makers would be trained to improve their work so they could sell their goods at higher prices to richer consumers. The idea was that Dharavis indigent would be better off. The builders and the government, of course, would be better off, too. Builders would pay a fee to be involved. Theyd also have to build new homes for the residents free of cost. Theyd get their money back, in spades presumably, by selling off the new buildings to wealthy investors. Everyone would win.

The plan was nothing if not grand, financially as well as morally. In 2007, Mehta told a reporter from Mint that if people were to initiate his design elsewhere, the world could be slum free by 2025. Mehta also made this promise to Bill Clinton, whose picture hangs proudly on the wall of Mehtas office, the former president smiling between the builder and his son.

Numerous activists railed against the project. They had many sound reasons for doing so, not all of which need to be enumerated here. Some do bear mentioning, though. First, only those residents who could prove that theyd lived in Dharavi since 2000 would be entitled to receive a free apartment. This meant that perhaps as many as half of Dharavis 500,000-plus residents would be displaced. Second, those who did qualify would be housed in approximately 47 per cent of Dharavis 1.7 sq. km surface area. The density would be unmanageable, no matter how high the new buildings were. Last, the majority of people in Dharavi I spoke to either had not heard of Mukesh Mehta and his plan or did not support it. To be fair, numerous residents fully endorsed the project and looked forward to a better life in a high-rise with a steady supply of water and a workable bathroom. Many sought the dignity that would come with having their own mailing address. I thought the book had a good case to make. But any argument against such a plan, sound as that argument may be, is still a negative argument. And negative arguments only take one so far.

I found a better argument, and a better method of putting the book together, after reading the work of Nobel-prize winning economist Amartya Sen. Sen opens Development As Freedom, a philosophical work concerned with social justice, with a parable about the limits of wealth. He graciously allowed me to reprint that story as the prologue to this book. In the parable, a woman named Maitreyee despairs when she learns that she cannot purchase immortality with her riches. Rather than pursuing the theological implications of Maitreyees conundrum, Sen considers the worldly aspects of Maitreyees wish to live forever. He focuses on the relationship between the money we have, the lives we live now, and the opportunities we have to improve our circumstances in the ways we see fit. Wealth is useful, Sen says, to the extent that it enlarges our freedom (which is, in Sens words, the ability to live as we would like) without encroaching on the freedom of those with whom we live. By extension, development, or the increase of ones wealth, is only beneficial to the extent that it expands ones freedom. Wealth is only useful to the extent that it can be used to help us live as we would like to live.

Sens parable raises questions that are relevant to the DRP. What about the freedom and the quality of life of residents who will be excluded from the new, integrated township? Furthermore, will residents who live gratis in a 300 sq. ft apartment be freer than they were before? Will they be living as they want to live? Will they be able to improve their living spaces as they could when they had their own place at ground level? They surely wont be able to add a second floor, as they could before. What happens when the elevator breaks, or the water gets cut off?

But those questions amount to arguments. What Sens parable really teaches is that stories are richer than arguments.

This book is therefore a collection of stories about the people who live in Dharavi. All of them are true. The people you meet in twenty-three of the twenty-four chapters that follow Sens prologue have acquired some measure of material wealthand a great deal of self-sufficiency. In the opening chapter, Sonia Faleiro demonstrates that freedom, as Sen conceives of it, begins at home. Faleiro writes about two fathers and their daughters. The first of the fathers, Mohammad Rais Khan, acquires a sense of self and purpose in part by keeping his wife and daughter tethered to their home, safe from the dangers of the worldnamely, men. The second, the late Dharavi-activist Waqar Khan, has shown his daughters how to be strong, ambitious individuals by encouraging them to go to school and pursue careers. As Faleiro shows, Khan has also taught his daughters how to participate in a community by restoring trust among Hindus and Muslims in the aftermath of the 199293 riots.

Next page