To the drivers of the FIA Medical Car who have conducted me safely round circuits worldwide, sometimes in appalling conditions and sometimes in appalling cars. Nevertheless, for the countless first laps, the many re-starts and the accidents to which I have been taken, I am grateful to have arrived in good condition. Over the years and over 300 Grands Prix there have been so many drivers of so many nationalities who have shouldered the responsibility of not screwing up the first lap that I cannot name them all. But I would like to say a special thank you to Alex Ribeiro and Frank Gardner who have driven me more than any other drivers and probably quicker than any others.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Max Mosley, President of the Fdration Internationale de lAutomobile, for his graceful permission to publish the data from the research activities of the FIA contained in Appendix 1 and similarly for the changes in the regulations to increase safety enforced by the FIA in Appendix 2, and for the Formula One Injury Statistics in Appendix 3. I would like publicly to record my thanks to him for his unlimited support of the work of the Research, Safety and Medical Commissions of the FIA, and for his personal support of my efforts as President of these Commissions. My thanks go also to Bernie Ecclestone, not only for his intense drive and support of my efforts, but also for his humour and the need for continuing vigilance to protect myself from his leg-pulling.

I am most grateful to Nigel Roebuck for accepting the onerous task of reading the text of the book and for his corrections of my inaccuracies. I much admire him as a writer and I hope his experience of reading my attempts were not too painful or boring.

Apart from memory, I have relied very heavily on Jacques Deschenauxs Marlboro Grand Prix Guide (19501999), and on a splendid book I found in a secondhand bookshop in Chipping Camden for 5 called The Grand Prix Drivers by Hazleton Publishing, edited by Steve Small and published in 1987. I have had great pleasure re-reading Innes Irelands two books, All Arms and Elbows and Grand Prix Driving Today. Autosport and the Grand Prix reports were fundamental for information, as was Autosports Grand Prix Review 2000.

I thank Lynne Sharpe and Roslyn Osinski for typing the manuscript. I thank Peter Wright of the FIA for technical help and for the definition of Units in Appendix 1, and Hubert Gramling of Mercedez Benz, Andrew Mellor and Brian Chi of the Transport Research Laboratory for all their help over the years.

Finally, I would like to thank Georgina Morley, Editorial Director at Macmillan, for allowing me to do another book, and Hazel Orme, my copy editor, for her diligence in keeping me to the straight and narrow. Any other cock-ups are my own responsibility.

FOREWORD

Sid Watkins new book paints graphic pictures of many of the people in Formula One Grand Prix racing. It also contains a great deal of humour. As in Life at the Limit, there are many behind the scenes tales of his untiring efforts constantly to improve the standards of safety in motor sport, efforts that benefit competitors in all categories. I worked very hard in my time in racing and I know how difficult a job it is to talk people into making improvements, not only to save life and prevent serious injury, but also to avoid the sort of accidents that in a great many cases should never have occurred. Sid Watkins is a glowing example to everyone in the sport of how to go about your business while retaining the respect and love of so many.

Sid is a remarkable man, with whom I have been friends for over twenty years. I have always been ready to support his cause for greater safety. He has taken on some pretty big challenges, sometimes against the institution and the very people who appointed him to his job but they, like me, respect him. He knows where to exert pressure and how to get his way. Sid is also a man who is available to everybody in the paddock in times of trouble, accident, injury or illness. He is totally reliable, with a wicked sense of humour and this sense of fun comes shining through in his book.

Sid Watkins has earned his place at the highest levels of respect and integrity within the sport and, if he ever gets tired of medicine, the speaking tour circuit would be a worthy alternative for his dry, often sarcastic wit and good clean humour.

Jackie Stewart, OBE

January 2001

INTRODUCTION

In October 1994 I started to write a book triggered by sadness at the loss of my good friend Ayrton Senna on 1 May 1994 at Imola. I was in Jerez de la Frontera recalling another horrible accident in which Martin Donnelly nearly lost his life. Life at the Limit was about the triumph and tragedy of Formula One racing, and it detailed the struggle I, and others, had to reach a high standard of medical safety at the circuits. It also had its share of behind the scenes stories about some of the sports most remarkable characters.

It is seven years since Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna died. In the years since then there have been many changes, changes which were triggered by the tragedies at Imola. Not the least among these is the attitudinal response to any injury in motor racing at Grand Prix level as shown by the response to the accidents of Oliver Panis and Michael Schumacher in 1997 and 1999 respectively. Max Mosley, President of the FIA, has since launched a zero option policy with the goal of zero mortality in the sport. Much research and development has gone towards the technical changes in the car, circuit design, safety, barrier development and personal protection in the cockpit. But this growing edge of research into the prevention of injury by study of the biophysics of accidents will always be accompanied by uncertainty. The unpredictable nature of events is inherent in the sport and provides the excitement and thrill for the drivers and their audience but also its dangers.

This new book relates the significant incidents between 1994 and 2000. There is also a race-by-race account of the millennium season, with some memories of my own life at the circuits and my views of the current F1 drivers. Finally, there are some happy memories of some of F1s golden oldies.

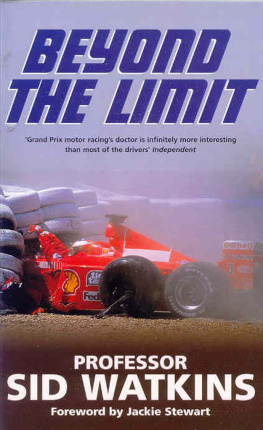

It becomes apparent in the Appendices which outline the continuing search for safety, and the statistics of injury, that the young men of Grand Prix racing are subjected to stresses far beyond previously accepted levels of human tolerance. In these circumstances it is fair and just to entitle this book Beyond the Limit.

Sid Watkins

Paris, France

10 January 2001

PART ONE

THE YEARS BETWEEN

1996

Melbourne: March

I guess the outstanding event at the beginning of 1996, before the season started, was Mika Hakkinens recovery from the devastating accident he suffered in Adelaide the previous year. After an initial period in hospital in Adelaide he came to London where it was necessary for him to undergo surgery as the accident had affected his hearing. Of course, he was a big hit with the nursing staff, who enjoyed having him around, particularly as he was quite well in himself and full of fun.

We all went off to Melbourne for the Australian Grand Prix, the first race of the season, which was also the first race to be held in Albert Park. There had been a good deal of protest about using the picturesque park as a race circuit. Just before the race, despite tight security, a bomb threat was received. The circuit people thought that whoever wanted to set it off was going to do so at the beginning of the first lap, provoking worry that it might actually disrupt the start. Bernie Ecclestone, with his usual sense of humour, said, Well, if we have to have two starts, thats more fun, so thats OK. In fact, nothing happened, but the first lap was somewhat explosive anyway.

Next page