H ave you ever watched a dog walking beside his owners, and carrying his own leash in his mouth? Have you seen the grin on that dog's face? I think it's because the dog is working. Boy, they're lucky I'm here to carry this leash. Dogs seem happiest when they're doing a job, and when they know they're doing it well.

Cats are another story. It's not that they won't work, but you might say they're self-employed. Fluffy may run her paws off catching mice today, if she's in the mood, but tomorrow it's Mouse? What mouse? I don't see any mouse.

For thousands of years, we humans have been taking advantage of the dog's determination to serve. We use dogs to help us in every way we can think of. Some of the jobs we give them are really cute. Some of the jobs are really hard. Some of the jobs kill them.

And here they are, after all this time still with that big goofy grin, still ready to do anything we ask them to.

CHAPTER ONE

In from the Cold

From high on a hillside, brother and sister watch the valley below. The Tall Ones are down there, doing strange things, as usual. The youngsters are fearful of the Tall Ones, but they are hollow with hunger, and their mouths water at the smell of food wafting up from the valley.

I'm going down there, says the brother. Come on.

But what if they ? His sister sniffs the air once more and relents. Together the two wolf cubs pad warily down the hill, toward the cooking-fire of the Stone Age family below.

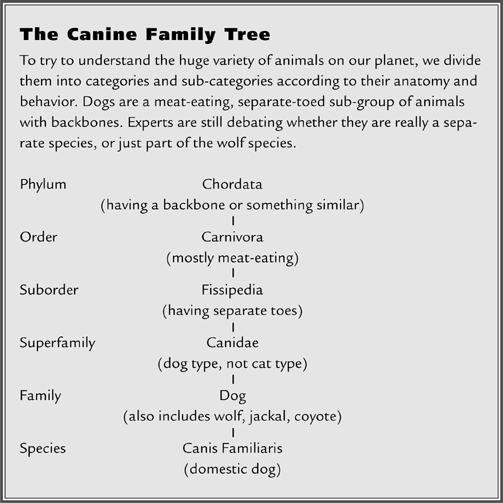

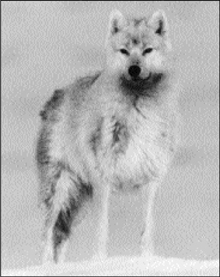

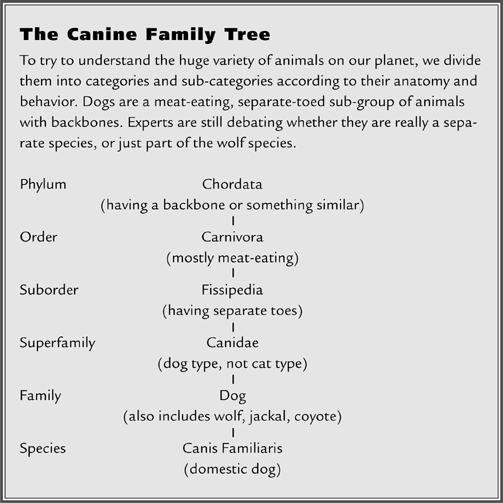

H ow long have dogs been part of our lives? How many centuries ago did the first dog sneak off with the family's dinner (Who, me?) or snuggle into the family bedding (Aw, please. It's cold out there)? We really don't know. The dog family is part of a larger animal family known as canids. The Latin name for the dog is Canis familiaris: common canid or more appropriately household canid. Most experts on canine paleontology the study of how the canid family developed agree that dogs are descended from early wolves, and that wolves first appeared at least a million years ago. At some point perhaps twenty or thirty thousand years ago some wolves began to live with people, and the extraordinary partnership of humans and canids began.

Maybe it all started as we fought over fresh meat. Or maybe motherless cubs were adopted by a kind-hearted family. Or maybe, in times of hardship, we worked out some kind of cooperation that helped us both. We'll never be sure how wolves and humans overcame their mutual suspicion, but we can guess this much: we came together partly because of the similarities between us.

Like people, wolves are social animals: they live in groups, with leaders and followers, and they help each other find food and raise families. Like our early ancestors, they often hunt animals much larger than themselves, using teamwork and persistence. Like us, they are constantly communicating with each other, by voice and body language. A wolf that made its way into a human community would soon understand the status of the various family members who was senior, who was junior and would learn the meanings of many human sounds, signals, and postures.

Why is it that we trust dogs with our lives, yet we accuse their close relative the intelligent, sociable wolf of everything from blowing down the little pig's straw house to menacing Red Riding Hood's grandmother?

Why is it that we trust dogs with our lives, yet we accuse their close relative the intelligent, sociable wolf of everything from blowing down the little pig's straw house to menacing Red Riding Hood's grandmother?

While our similarities may have helped bring us together, our differences have made our partnership even more valuable. We humans have sharp eyesight and excellent color vision, and the way our eyes are positioned on our head gives us a good sense of distance; wolves have keen night vision, and phenomenal powers of hearing and smell. We have the brains for imaginative long-range planning; the wolf has the muscles for speed and power. We have agile hands that are free to make and brandish weapons; the wolf grows fearsome weapons on jaws and feet. Together, what a team we make!

From Wolf to Dog

How did those early wolves turn into the immense range of dogs we have today, from miniature poodle to Great Dane? The process probably started when people were first settling into permanent communities. It's likely that some wolves learned to hang around these settlements, stealing meat and scavenging scraps of garbage.

This primitive rock art from Tassili-n-ajer, in Algeria, shows people and canids hunting as a team in the Stone Age. The upcurved tails of the canids suggest that they are dogs, not wolves.

This primitive rock art from Tassili-n-ajer, in Algeria, shows people and canids hunting as a team in the Stone Age. The upcurved tails of the canids suggest that they are dogs, not wolves.

As one litter after another was born on the edge of human society, probably only a few wolves were fearless enough to be comfortable so close to people, while the others retreated to the wild.

Did humans capture some of the wolf cubs and make them part of the family? Did a few wolves become so confident around people that they moved into the settlement of their own free will? However it happened, a number of these wolves who didn't mind people eventually started living inside the community and raising cubs there. Year after year, as generations of cubs grew up, the young wolves who were shy of people left the settlement and moved to the wild. The ones who were aggressive toward people were killed or driven away. Only a handful of the animals those who were not too timid and not too aggressive remained.

As these few wolves interbred among themselves, and passed their genes on to cubs and grandcubs, the generations came to look less and less like their cousins in the wild. Before long perhaps within one human lifetime these animals had an appearance and behavior that we today would recognize as doglike.

Why did they change so much? Many explanations have been suggested for how each separate change in size, color, teeth, and so on may have helped them fit better into human society. But the answer may be even simpler. When genetic information (DNA) is passed from parents to children, certain characteristics that appear to be unrelated are in fact linked together that is, a child who inherits one characteristic is likely to inherit the linked ones as well. (For example, some breeds of dog have a genetic link between deafness and white hair; the white puppies in a litter are more likely to be deaf.) It's possible that when the temperament of the village wolves was evolving to be more domesticated, a number of other characteristics (size, color, teeth, etc.) were evolving too, because they happened to be genetically linked to temperament.

Why is it that we trust dogs with our lives, yet we accuse their close relative the intelligent, sociable wolf of everything from blowing down the little pig's straw house to menacing Red Riding Hood's grandmother?

Why is it that we trust dogs with our lives, yet we accuse their close relative the intelligent, sociable wolf of everything from blowing down the little pig's straw house to menacing Red Riding Hood's grandmother?