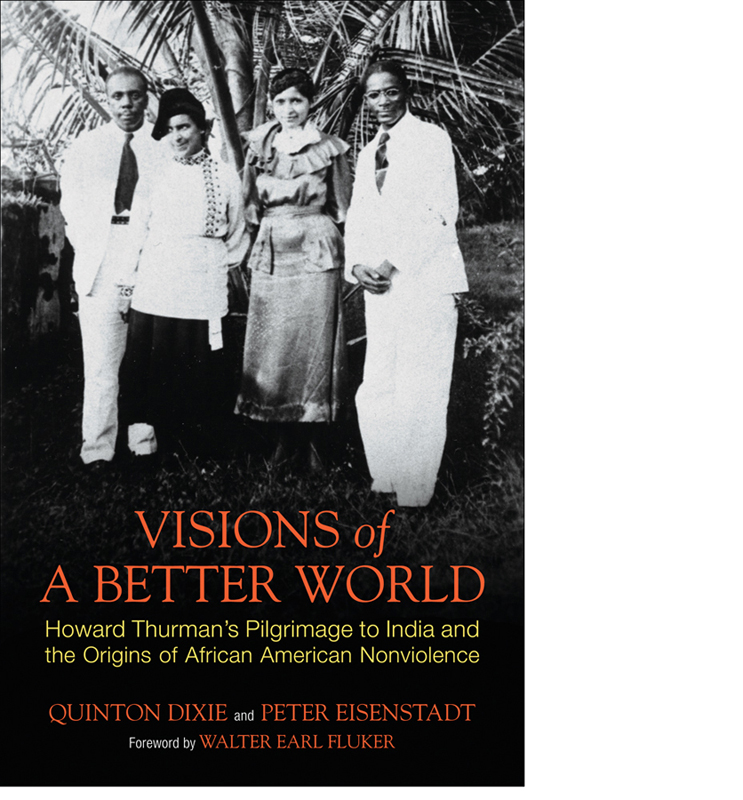

Visions of a Better World

Howard Thurmans Pilgrimage to India and the Origins of African American Nonviolence

Quinton H. Dixie & Peter Eisenstadt

Beacon Press, Boston

Contents

by Walter Earl Fluker

Foreword

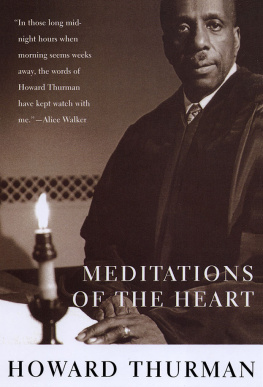

We need a moral prophetic minority of all colors who muster the courage to question the powers that be, the courage to be impatient with evil and patient with people, and the courage to fight for social justice. Such courage rests on a deep democratic vision of a better world that lures us and a blood-drenched hope that sustains us.

Cornel West

One of the many challenges of directing a publishing project like the Howard Thurman Papers Project is the problem of too much data. In most respects it is a good problem to have. At the same time, the practical concerns of modern publishing render it impossible to make available to the masses all the information one is able to gather about the subject. Moreover, there are always themes and stories that dont make it into the volumes or portraits of a person that cry out for more light. In Visions of a Better World , Quinton Dixie and Peter Eisenstadt shed additional light on a pivotal moment in the life of Howard Thurmanhis pilgrimage to India, Burma, and Ceylon in 1935 and 1936. Anyone who knows anything about Thurman is aware of the journey, but few people know the breadth of the trip and the depth of its impact on him. The image of Howard Thurman embedded in the public consciousness is that of a wise, introspective mystic concerned with maximizing his individual spiritual assets. What Dixie and Eisenstadt have been able to show is a courageous and radical Thurman. Indeed, during the 1930s and 1940s he was a radical pacifist, a radical integrationist, and a radical follower of Jesus. All this culminated in his commitment to social justice through nonviolent, noncooperation with evil.

Nonviolence , a term popularized and probably coined by Gandhi, has gone by many names: direct action, civil disobedience, passive resistance, satyagraha, ahimsa, and many others in many different lands. Its American history, prior to Gandhi, was already extensive. Perhaps the original pioneers of nonviolent resistance, at least as a conscious political tactic, were American abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison and Henry David Thoreau, who (via Tolstoy) were both major influences on Gandhis early thinking. African Americans, in the abolitionist movement, in bondage, and after emancipation, regularly used civil disobedience as a tactic to make their lives endurable. For Thurman, the Negro spirituals were an unparalleled record of the various ways in which enslaved African Americans used religion to find the courage to resist their masters, knowing that challenges to their dominance could have fatal consequences. In Gods presence, Thurman would write of the message of the spirituals, there would be freedom; slavery is no part of the purpose or the plan of God. Rosa Parkss challenge to segregated public transportation had many forerunners, among them Frederick Douglass, dating back to the antebellum period. The tactic of challenging segregation in public entertainment by small integrated groups demanding their collective admission dates back to approximately 1910.

But Gandhis example transformed nonviolence from an occasional tactic into a political philosophy, a religious belief, and a way of life. American admirers of Gandhi, black and white, started to proliferate during the interwar years. Among those who fell within the ambit of Gandhi and his ideals was Howard Thurman. From his undergraduate days at Morehouse College in Atlanta in the early 1920s, he was a member of the premier Christian pacifist organization in the country, the Fellowship of Reconciliation. He soon became its most prominent African American member. If Thurman was opposed to militarism and foreign wars, the core of his pacifism was always an opposition to the violence inherent in racial oppression at home. This was the subject of an important article by Thurman written as early as 1929, one of the first by a black author to explicitly link nonviolent resistance to the struggle against Jim Crow.

Visions of a Better World places Thurman where he properly belongsat the beginning of the African American conversation about nonviolence and social change. His vision was deeply rooted in his sense of what was possible in a society that chose to live out its democratic ideals. And it was grounded in the hope of a people who had suffered for righteousness sake. Inspired by what he learned in India, Thurman went on to provide the spiritual blueprint for the civil rights movement.

Walter Earl Fluker

Boston, Massachusetts

Introduction

Long before the two men met, long before he had any inkling that a meeting would ever be possible, Howard Thurman had been preparing for an encounter with Mohandas K. (Mahatma) Gandhi. When the meeting took place, in early 1936, Thurman and his colleagues would be the first African Americans to meet with the famous leader of the Indian independence movement. Thurmans time in India was less a transformation than a confirmation of what had long been his core belief: Christianity, as it had been traditionally practiced, was incapable of taking on the greatest challenge of the day, social and racial inequality. Howard Thurman was never a firebrand, and to some, who did not pay close attention to his message, he seemed to be an otherworldly mystic with little time to spare for any down-to-earth realities, including the practical politics of American minorities fighting for their civil rights. But for those who listened carefully, including many in the rising generation of African American leaders in the 1930s and 1940s, among them James Farmer, Pauli Murray, and Martin Luther King Jr., they heard a call for a new Christianityone without dogmas, dedicated to the principles of pacifism and nonviolence, and utterly committed to the task of eradicating Jim Crow in all its varieties and manifestations. It is true that Thurman was never primarily a writer or speaker on political topics. But in his public appearances, articles, and teaching in the 1930s and 1940s, and both in his own right and through his broader contagion, he was one of the creators of a distinctly African American path to radical Christian nonviolence.

On October 21, 1935, Howard Thurman reached Ceylons major port and capital city, Colombo. When Thurman arrived in Colombo he had been traveling by rail and boat for a month, since he and his party had left New York Harbor. The time Thurman spent in India would be a turning point in his life and a watershed in the gathering struggle of African Americans for racial equality.

At the time of his arrival in Ceylon, Thurman was thirty-five years old. He was an ordained Baptist minister and a professor of religion at Howard University, where he led the weekly services at Howards Rankin Chapel. If Thurman was, as one of the organizers of the Pilgrimage of Friendship remarked, somewhat long in the tooth to be a student Christian, there was no doubt that he was already acclaimed as one of the leading young ministers of his generation and a man who had already amassed a considerable reputation as a preacher and religious thinker, before audiences both white and black. He was, the organizers of the Negro Delegation thought, the perfect person to bring the message of American Christianity to India.

The delegation was in India at the request of the head of the Student Christian Movement in India, Ceylon, and Burma: Augustine Ralla Ram. Ralla Ram had wanted a delegation of Negroes to visit because he felt they could relate better and would be more fully accepted than the white missionaries who comprised the vast majority of the overseas Christians coming to India. Unlike most of their predecessors, the Negro Delegation was not coming to India as evangelists, as would-be savers of souls, or as bringers of Christ to India. (Thurman found it typical of Western pretensions that most missionaries ignored the fact that Christianity had been in India since about the third century ce , long before any Angles or Saxons had adopted the new faith. ) Rather than proselytize or in any conventional way preach the gospel, the Negro Delegation was in Asia to represent one version, their version, of African American Christianity to an Asian audience and to present the complexities of being black and Christian in 1930s America. How this would be received, how the members of the Negro Delegation would meet or disappoint expectations, they were about to find out.