Contents

Guide

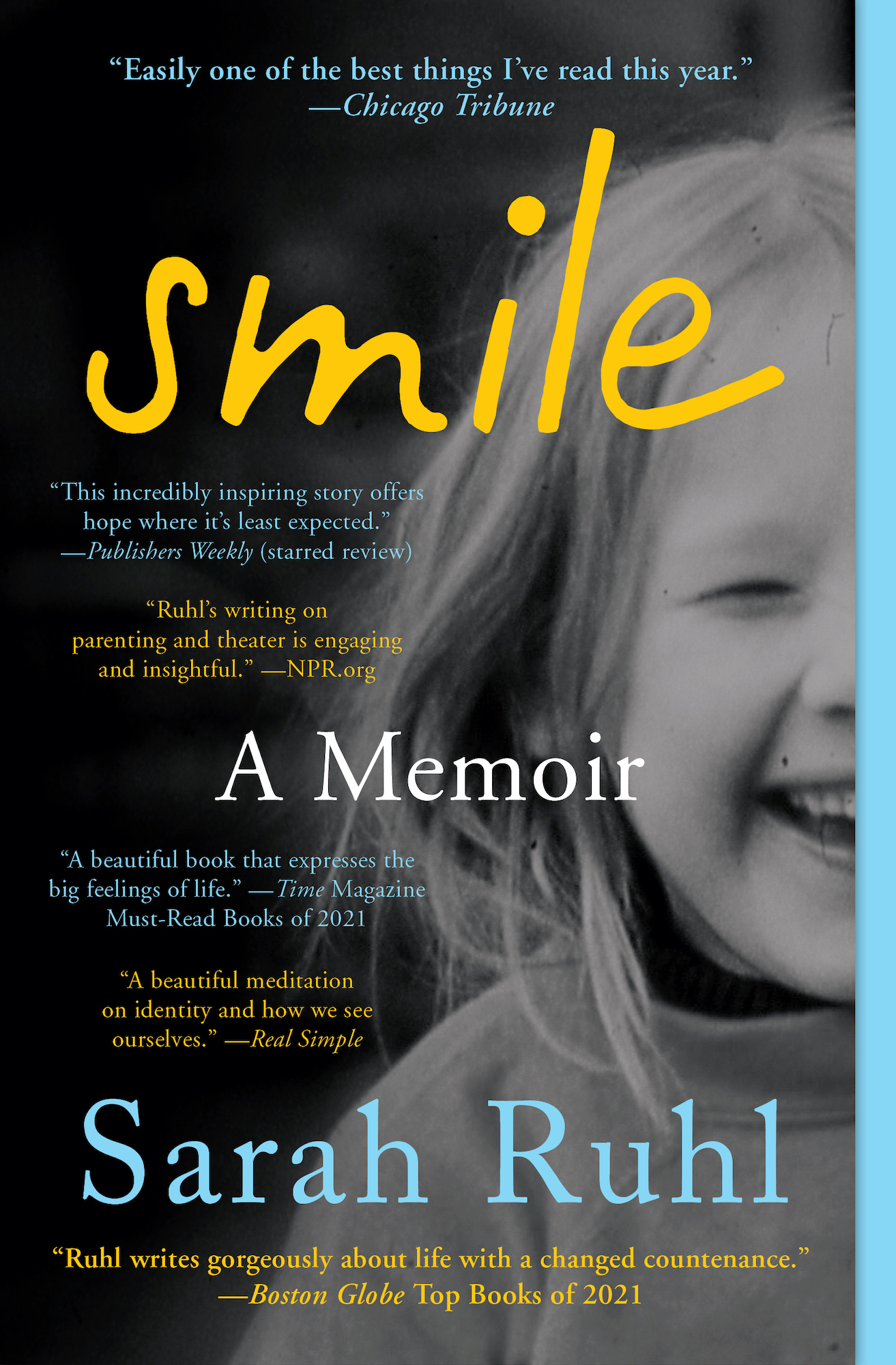

Easily one of the best things Ive read this year.

Chicago Tribune

Smile

This incredibly inspiring story offers hope where its least expected.

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Ruhls writing on parenting and theater is engaging and insightful. NPR.org

A Memoir

A beautiful book that expresses the big feelings of life. Time Magazine Must-Read Books of 2021

A beautiful meditation on identity and how we see ourselves. Real Simple

Sarah Ruhl

Ruhl writes gorgeously about life with a changed countenance.

Boston Globe Top Books of 2021

To all the many doctors and healers of every stripe who have helped me these past ten years.

But mostly to the main doctor in my life, my husband, Tony Charuvastra, who sees me through, and sees me, every day.

Considering how common illness is, how tremendous the spiritual change that it brings, how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed it becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love, battle, jealousy among the prime themes of literature.

V IRGINIA W OOLF , O N B EING I LL (1926)

Sometimes your joy is the source of your smile, but sometimes your smile can be the source of your joy.

T HICH N HAT H ANH

CHAPTER 1

Twins

T en years ago, my smile walked off my face, and wandered out in the world. This is the story of my asking it to come back. This is a story of how I learned to make my way when my body stopped obeying my heart.

But this story begins with hopethe very particular hope of a birth to come. I was lying down in a dressing gown, cold gel on my belly, waiting as the lab technician looked for a heartbeat. I already had a three-year-old girl, and was expecting my second child. I was also expecting to have a play Id written to be performed on Broadway in five months, and was slightly nervous about the potential collision of two kinds of abundance.

Suddenly the lab technician pointed to the screen and said, Do you know what that is?

No, I said.

I flashed on the ultrasound Id had before miscarrying my second pregnancy, when the obstetrician had said the fetus looked not quite right and probably wouldnt last. Dont, like, go out and get drunk, though, she had said in a tone not quite teasing, just in case its viable.

Uh, not to worry, I had said, wondering what gave her the impression that I would go out and get wasted that weekend.

So this time, I feared the worst as I lay there, nervous, while the lab technician squinted at a screen I could not see. Look! she said, pointing. There was movement, a heart beating, it seemed to me. A heartbeat, thats good, I thought, but what was wrong? Why was her brow furrowed? Was she alarmed, or, wait, was she pleased? Did you use fertility treatments? she asked.

No, I said.

Well, she said, you have twins!

Oh! I said.

Do twins run in your family?

No, I said. My mind raced to keep up with my body.

You can go to the waiting room, she said. Ill give you a list of new providers. We can no longer be your ob-gyn because your pregnancy is now considered high-risk.

This was a great deal to absorbthat I had two babies inside me and was also now considered high-risk, so much so that they wanted to get me out of their SoHo office as soon as possible before I got preeclampsia and sued them.

I got dressed. I happened to be alone for this appointment; I had planned to meet my husband afterwards for lunch, where we would celebrate if there was a heartbeat, or commiserate if there was not. Now I was sorry Id come alone. I wanted to tell my husband, Tony, the news immediately, but it also seemed strange to reveal such big tidings over the phone.

So I texted him: Meet me at Gramercy Tavern instead of at Rice.

Twins? he texted back.

Gramercy Tavern was closed for lunch. Tony and I went to Rice, as planned. We were both in shock; Tony, on top of the shock, evinced buoyancy, elation. Coming from a family of three siblings, hed always wanted three. Being from a family of two, Id settled on two. Id even, at one point, settled on one, when I read in an Alice Walker essay that women writers should only have one child if they hoped to remain writers. With one child you can move, wrote Walker. With more than one youre a sitting duck.

At lunch, Tony and I talked about how my miscarried child had wandered back, not to be excluded from this birth. We talked about how we would manage with three. I told Tony my fears: that my body could not contain this much abundance and that Id never write again. He said he had faith in my body and mind.

At the end of the meal, I got a fortune cookie. I cracked it open. It read: Deliver what is inside you, and it will save your life.

Everyone seemed jubilant about the news, but I was overwhelmed. I found myself feeling vaguely sick when thumbing through books about multiples in the pregnancy section of the bookstore. There were pictures of breastfeeding triplets, and I didnt want to know about all that. It struck me as grotesque, as though I had once been a woman but was now hurtling towards becoming full mammal, all breasts and logistics. I worried that I wouldnt be able to give enough attention to my three-year-old, Anna. I feared that my body wouldnt tolerate two babies; I feared that my writing wouldnt survive three children.

I called my mother with the news. I gave off a scent of How can this have happened?

My mother paused, then said, Well, your great-aunt Laura had twins.

Why didnt I know?

They were stillborn, she said.

Twins run on the mothers side, skipping a generation. Poor great-aunt Laura, whose heartbreak I never knew. Somewhere in Iowa in the 1950s she buried two babies on the prairie and never spoke of it. I imagined their graves on some grassy plain. I wondered whether Laura gave them names; Laura was dead so I couldnt ask her. The ghosts of my great-aunt Lauras babies would haunt me for the rest of the pregnancy.

When I told friends I was having twins, I was as apt to cry as to laugh. My dear friend Kathleen, a playwright, from a large Irish Catholic family, comforted me, saying, I love big families. Small families are so boring in comparison. Kathleen had already raised two daughters, and had shown me all the ropes, talking me through potty training and tantrums. Her most comforting phrase was, Im sure its just a stage. At this seismic news she said quite simply, Ill help you. And I knew she would.

Three months pregnant and terrified, I visited my former playwriting teacher Paula Vogel and her wife, Anne Fausto Sterling, an eminent feminist biologist, on Cape Cod. They said, come, well grill fish, well take care of you. Paula is the reason I write plays. She has the ferocity of a general in battle, the joy and humor of a street performer, and the tenderness of a mother. That week, she entertained Anna with tissues she made into a puppet. Anna laughed with joy. I was quiet. Paula observed me. Whats wrong? she asked. She gave me her conjuring, summoning look.

Will I ever write again? I asked her.

Yes, you will, she promised. I looked out at the ocean. This was the same view Paula had shown me years ago, when shed invited her graduate students out to her Cape Cod home, entreated us to look out the window, and say to ourselves a mantra

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1 Twins

Twins