Table of Contents

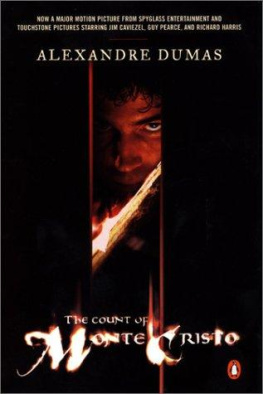

Alexandre Dumas was born July 24, 1802, and died December 5, 1870. He was the author of over ninety plays and many novels, including the famous Three Musketeers trilogy (1844) and The Man in the Iron Mask (1850). His grandfather was a French nobleman who lived in Santo Domingo, Hispaniola, and his grandmother an Afro-Caribbean slave. Dumass father, a general in Napoleons army, fell out of favor, then died when Alexandre was four years old, leaving his family in poverty. As a youth Dumas was a storyteller with a vivid imagination, and after moving to Paris at age twenty-one, he eventually turned his talent to writing plays, producing Henri III et Sa Cour to a triumphant reception. In 1824, he fathered an illegitimate son, Alexandre Dumas fils, who grew up to be a celebrated writer himself. After taking part in the French revolution of July 1830, he married his mistress, Ida Ferrier, but left her after using up her entire dowry. He was a lavish spender, and in 1848, after the successful publication of Le Comte de Monte Cristo (1844-45), he built his own Chateau de Monte Cristo, which cost more than 500,000 francs. Soon bankrupt, he was forced to flee to Belgium to escape his creditors. His travels included a trip to Russia, then one to Italy, where he joined the fight for its independence. He died penniless but optimistic, saying of death, I shall tell her a story, and she will be kind to me.

Roger Celestin is a professor of French and comparative literature at the University of Connecticut. He has published on French authors from the Renaissance to the twentieth century and is coeditor of the journal Contemporary French & Francophone Studies/SITES.

Introduction

The name of Alexandre Dumas is more than

French, it is European; it is more than Euro

pean, it is universal.

Victor Hugo

Alexandre Dumaswhose name is synonymous the world over with adventure and romance, duels at dawn and a fabulous treasure, a villainous cardinal and valiant musketeers, a man in an iron mask and an avenging countis undoubtedly the most popular author of a country that has produced a substantial number of them, from Victor Hugo and Honor de Balzac to Jules Verne and mile Zola, to name only a few of those nineteenth-century writers who, like Dumas, had and continue to have a wide readership.

The Panthon is where France, that most literary of countries, lays to rest its great men (and, sometimes, women). Built as a church by Louis XV, it was turned into a public building by the revolutionaries of 1789 even before it was completed and became the resting site where the new Republic, the grateful fatherland, honored its illustrious dead. Voltaire and Rousseau are there, as are Victor Hugo and Marie Curie. In 2002, exactly two centuries after the year of his birth, the remains of Alexandre Dumas were taken from Villers-Cotterts, the small town where he was born fifty miles northeast of Paris, to be put to rest in the Panthon. His remains had already been moved once, to Villers-Cotterts from the country cemetery at Puys, a small village in Normandy, where he was quietly buried in 1870 like a simple character in a short story by Guy de Maupassant, as French president Jacques Chirac said in his speech on the Panthons esplanade before Dumas was taken inside to his final resting place. At the outset of that speech, one of the last events of a weeklong national celebration of Dumass life and work, the French president also mentioned that in bringing Dumass remains to the Panthon, the Republic is not only honoring Alexandre Dumass genius ... it is righting a wrong. A wrong that has branded him since his childhood, as it had already branded his slave ancestors with an iron.

One slave ancestor to whom Chirac referred is Dumass grandmother, a black affranchie, or freed slave, from Haiti, then a French colony. Dumass grandfather, a nobleman from Normandy, was the marquis Antoine-Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie; like so many others at that time he had gone to try his luck in the thriving colony. He bought a plantation and, on March 27, 1762, had a son by Marie-Cessette Dumas, who worked on that plantation. Andr Maurois, the author of what is probably the most comprehensive of the Dumas biographies, tells us the son was baptized but that there is no document proving a marriage took place. Marie-Cessette Dumas died ten years later and the marquis eventually went back to France with his son, Thomas-Alexandre. The Normandy nobleman lost his estates during the Revolution of 1789 but his son, who had joined the army under his mothers maiden name, distinguished himself during Napoleons glory years and became a general at age thirty-one. He married Marie-Louise Elizabeth Labouret, the daughter of an innkeeper at Villers-Cotterts, where their son Alexandre was born in 1802. In post-revolutionary France, the future author of The Count of Monte Cristo and of The Three Musketeers, the son of an aristocratic but republican general and of a daughter of the small provincial bourgeoisie, thus represented a kind of reconciliation of classes. Dumass social origins were also reflected in the breadth of his plays and novels peopled by characters who included everything from chambermaids, smugglers, and sailors to musketeers, cardinals, and kings. As Dumas writes in his Memoirs: I am made of that dual element, both aristocratic and of the people, aristocratic through my father, of the people through my mother, and no one carries together in their heart more than I do respectful admiration for the great and deep sympathy for the unfortunate.

When Alexandre was four, the general died. He had quarreled with Napoleon and was not receiving his army pension; his family was left to manage on what little they had. The boys education was uneven, to say the least. Bored by Latin and music, Alexandre expressed an interest only in hunting and the handling of weapons, and he had only two passions: women and literature. He was initiated into the charms of the former at sixteen by a slightly older young lady of Villers-Cotterets and exposed to the intricacies of the latter by a young aristocrat, Adolphe de Leuven, a friend of his family. The two collaborated on several plays, the first of Dumass writings. Leuven also convinced Dumas that Paris was the only place in the world for a young man determined to have a literary career.

At twenty-one, thanks to his beautiful handwriting and some of his fathers still-influential aristocratic connections, Dumas finds employment as a clerk in the secretariat of Louis-Philippe, duc dOrlans and future king of France. The young provincial author discovers the Paris of the Restoration, the literary salons, and the Romantics, who are in the process of overthrowing the staid forms of French classicism and subverting their recycling by the conservative literary establishment. And for the first time in his life Dumas begins to read ravenously, making up for lost time. Like an autodidact, he reads everything, and like the Romantics, he reads Schiller, Goethe, and Walter Scott, a major influence on his own invention of the French historical novel.

It is in the theater, however, that Dumas first makes a name for himself. After the first few years of apprenticeship and lack of success, he becomes famous overnight when his play Henry III and His Court opens to tumultuous acclaim at the Comdie-Franaise on February 11, 1829. After this consecration, Dumas quickly becomes one of the best-known-and certainly one of the most activeplaywrights in France and one of the main members of the Romantic movement. His initial success with