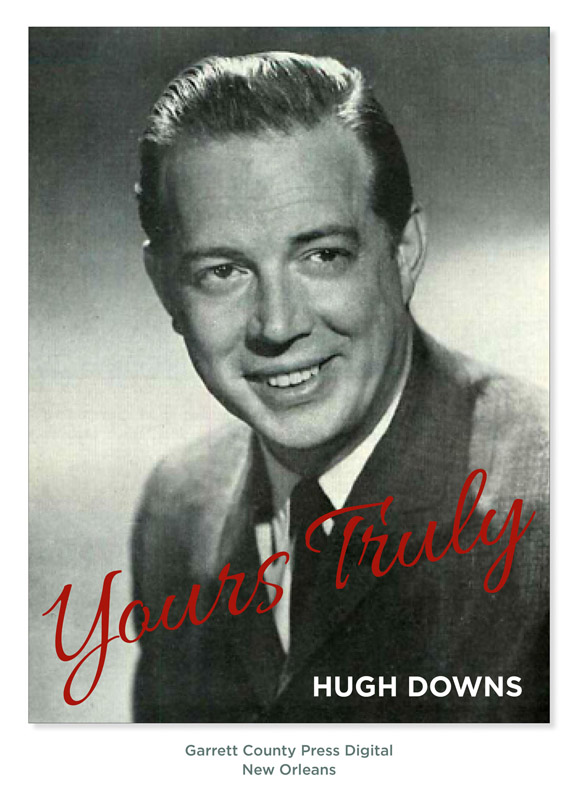

Introduction

I N A DISCUSSION on the Jack Paar show in the spring of 1959 I was asked what I thought of progressive education. I said I believed progressive education was a manifest failure and that it was asinine. I take no particular pride in this answeras a matter of fact its lacking a little in dignitybut it said what I feel, and if I were called on to restate it, I would say I believe progressive education is a manifest failure and that it is asinine.

Within hours I had stacks of wires and within days, a flood of mail lauding and condemning my attitude. It ranged from maudlin reactionary praise to thoughtful pleas that I re-read Deweys Schools of Tomorrow. It came from people whose children were in serious difficulty in schools which have thrown out all old-fashioned teaching methods, and with them, much that was good and essential to disciplined learning. It came in threatening blasts from chronic malcontents who defend anything (however chaotic) which does away with any method tainted by tradition. In short, it came from both sides and ranged in the case of each side from literate essays to crank abuse.

I learned from this response that there was far more reaction to a comment on education than I would have guessed, and that on this issue those in sympathy with my opinion were apparently as prone to write as those critical of it. This is not usually the case, and I think it means America is more deeply concerned on the citizen level about its present education picture than legislators and bodies of officialdom are aware.

The incident made me think. Why, I asked myself, have I the opportunity to give an opinion so casually, and have it amplified so that a nation can hear it and comment on it? Have I the right to do this?

There is no question of my right to speak freely. The question is, has anyone the right even for a minute to take a broadcast channel belonging to the public and sound off in a voice many millions of times louder than the one nature gave him.

I think the right exists.

I do not think the question has to do with rights. Merely that it happens makes it a fact to be dealt with, and the question is of responsibility, not rights.

While it must be agreed that the television industry today is a giant whose influence is incalculable, it is, nevertheless, in its infancy. Those who have become enmeshed in the phenomenal growth of this gigantic infant are often too deeply involved to recognize the immaturity of the medium, assuming in the heat of daily pressures that they, along with TV itself, have arrived at the ultimate of importance and grandeur.

In my own view, we (meaning those who make up the television studio world) still have much to learn. We have by no means arrived, simply because we are not yet fully aware of the tremendous power we wield either for good or for evil. Nor have most of us come to the realization that we have a responsibility to use such vast power thoughtfully and, if possible, wisely.

For some time it has been my wish to set down the things I believe about broadcasting and its personalities, and in the course of doing so, to tell my own story as it relates in its small way to this fast-moving, fascinating world. From my vantage point on the Jack Paar show and others, I have seen public reactions which show the fantastic ability of masses of people to size up a situation with speedy and brilliant insight, and I see other reactions that prove you can still fool all the people some of the time and some of the people all of the time.

What the public sees on the screen is like the exposed portion of an iceberg. Supporting the pinnacle is a much greater mass, hidden from view below the surface. Behind the scenesoff camerais a greater drama than anything flashed over the airways.

Just what is television and how does it fit the so-called American Way of Life? Is its function purely one of entertainment? A great many stars and producers: seem to think so. Is it a vital communications medium? Watching Ed Murrows See It Now or World Wide 60 or other documentary productions, you gain a sense of TVs educational power. Perhaps it is both these things or many things rolled into one. In any case, its role in American life today is so important that we must accept it as a force in modem democracy.

If you believe in democracy, you believe the public knows whats best, at least in the long run. And if the public knows whats best, then it doesnt need arbiters of taste and morality, government-appointed or self-appointed, to determine its entertainment fare or to act as filters in its communication channels. In short, it doesnt need censors.

If the public doesnt need censors, then free-enterprise competitive broadcasting is the kind of broadcasting that will most surely improve itself, artistically, educationally and morally, because the public will give its loyalty to those shows and concepts which are the best, in the highest meaning of the word.

If you disagree with this concept of democratic controls, I would want to defend your right to do so. However, I would like to be sure that we arent thinking of different definitions of the word censor. Libel and postal laws, in my view, are not necessarily censorial, since they do not prohibit expression. Nor is the action of any decency type of organization which simply reviews and recommends for its own group. A network continuity acceptance chief, anxious to prevent offense that would ultimately result in a drop in viewing, is not a censor, for he is attempting to abide by public demand, and if he errs, he is soon forced to recognize his error by the publics reaction. But any person who prohibits, destroys, blocks, or impedes productions to satisfy his personal beliefs or prejudices while claiming his action is for the good of the public, is a censor.

Assuming that free-enterprise competitive broadcasting is best, the broadcaster who seeks longevity in his career will want an element in his broadcast technique that survives competitionan element that never gets stale, that can never be overexposed. This element is honesty.

For purely expedient reasons (if reasons of principle are not operative) the broadcaster who wishes to last will start with honesty as his foundation. He is therefore the keeper of a most sacred trust, to himself as well as his fellow citizens. To betray this trust is to open the door to censors and to lay a momentary blight on the democratic process.

![Robert Hugh Benson [Benson - Robert Hugh Benson Collection [11 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/139831/thumbs/robert-hugh-benson-benson-robert-hugh-benson.jpg)