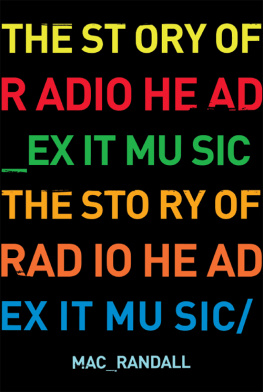

Copyright 2011 Omnibus Press

This edition 2011 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

EISBN: 978-0-85712-695-5

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

PREFACE TO REVISED EDITION

More than three years have passed since the first edition of Exit Music was published. In the time since, Radiohead have turned from a popular and well-respected rock band into a stadium-filling art music phenomenon. Their audience, already large in the late 90s, has become massive; their albums now debut at the top of sales charts across the globe. The music industry looks to them for artistic hints, awaiting their next move to see whether it might yield the key to that always elusive new direction. And, indulging in the sincerest form of flattery, countless bands copy their style. The success of acts like Travis, Coldplay, Doves, Muse and many others, who take their inspiration from different phases of Radioheads career and make a more-than-decent living out of it, is testament to the impact Yorke, Greenwood, OBrien, Greenwood and Selway have had on those who play, listen to, profit from and argue about music.

Ive watched this development with a certain amount of purely egotistical pride. I wrote a book about Radiohead because I thought they were important, and I suspected theyd become more so; subsequent events have proved my suspicions correct. But theres more to it than that. In the last three years, Ive also gained an even deeper respect for the band, and for their audience. For both have accomplished great things.

Radiohead reacted to the stardom that OK Computer brought them in 1997 the same way they reacted to the stardom that Creep had brought them in 1993: by jettisoning the sound that made them famous and trying another one. With no guide but their instincts, this proved difficult. It almost killed the group. But for them, there was no other choice; they had to keep moving. Suddenly the music they made was obscure, abstract, all ominous atmosphere and sharp angles. On first listen, it didnt make much sense. And yet people kept listening to it more people than had ever listened to the band before and as they listened, they found the sense.

For me, this is the most inspiring part of the Radiohead story to date. Kid A, the bands fourth album, released in October 2000, was a calculated risk, a conscious departure from pop norms that challenged the rest of the world. This is what we do now, take it or leave it. It sneered at commerciality. And then it went and debuted at No. 1 on the American and British charts. By making the music they wanted, and conceding nothing to the forces of the marketplace, Radiohead rocketed from star to superstar status. The capacity of the general consumer to comprehend a work of art had, once again, been underestimated.

You could argue that this was just a passing wave, that the Kid A hype dragged everyone along with it, that Radiohead were only the trendy thing to be into that month. So how then to explain the performance of the bands next album, Amnesiac, in June 2001? Despite being even more thorny than Kid A, it sold nearly as well, hitting No. 2 in Billboard and No. 1 in the NME. It seemed that millions of people were listening to Radiohead, not because it was hip to do so, but because they actually liked the music.

True art never remains static. It continually evolves, as do our lives and thoughts. And while theres plenty of joy to be found in the comfort of the familiar, whether that be the plot of a mystery novel or the chorus of a pop song, too much predictability in an artistic endeavour palls over time, precisely because it doesnt match the bewildering unpredictability of our own experiences. Listening to the music that Radiohead have made over the last decade and more, from the Drill EP to Hail To The Thief, its clear that this band have a capacity for evolution matched by few, if any, of their contemporaries. Each album, each single sounds remarkably different from its predecessor. In that way, Radioheads work feels closer to life than most pop music.

Yet a few stylistic elements continue to be consistent in the Radiohead canon: chord progressions built around a single note or pivot point, a fondness for odd meters, Thom Yorkes plaintive vocals, a general air of thoughtful melancholy. And the emotional power of these elements has only grown with the passing years. No wonder this band have so many fans. For over a decade now, theyve always managed to find the perfect musical mix of the stable and the unhinged.

Not only in their music but in all other aspects of their career as well, Radiohead have been admirable in their insistence on going their own way and proving that it was the right way. For the no logo tent tour of 2000, the band performed in a self-designed environment free of advertising; in doing so, they made both a political and cultural statement and, consciously or unconsciously, conveyed to their fans something akin to the ancient notion that playing and listening to music occurs in a sacred space, set apart from the rest of the world. Radioheads early realisation of the Internets significance is also noteworthy; its a medium theyve exploited (if thats the right word) with real smarts. In many ways, its become as important a means of communication as the songs themselves, and its certainly brought the band closer to their audience, a situation that both parties appreciate.

To say that a musician cares about his fans is one of the hoariest showbiz clichs in existence. But a close observation of Radioheads career, and the intelligence and respect with which theyve gone about all their public dealings, makes it hard to come to any other conclusion than that they do care about their fans very much. Maybe theres some connection here with the reason why this band have stuck together so long, and why theyve remained so close to their hometown of Oxford. One gets the feeling that in the Radiohead camp, loyalty is a virtue second to none.

Successful organisations, of course, tend to grow larger over time, and these days its tougher for journalists to reach the members of Radiohead through the various protective layers of management and representation. Once again, I was not able to convince them to cooperate with me for the updated edition of this book. For the previous edition, I had the advantage of a backlog of interview material collected over three years. This time I dont. But its a different story now, a different era, and so I take a different, more critical approach, which I hope will still do justice to the band. My central focus, though, remains the same: Radioheads music. And that, no matter how many times I hear it, remains extraordinary.