Also by Stanley Cohen

The Game They Played (1977, 2001)

The Man in the Crowd: Confessions of a Sports Addict (1981)

A Magic Summer: The 69 Mets (1988, 2003)

Dodgers! The First 100 Years (1990)

Willies Game (with Willie Mosconi, 1993)

Tough Talk (with Martin Garbus, 1998)

The Wrong Men: Americas Epidemic of Wrongful Death

Row Convictions (2003)

The Execution of Officer Becker (2006)

Beating the Odds (with Brandon Lang, 2009)

The Man in the Crowd: A Fans Notes on Four Generations

of New York Baseball (2012)

Convicting the Innocent: Death Row and Americas Broken System of Justice (2016)

Copyright 2018 by Stanley Cohen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

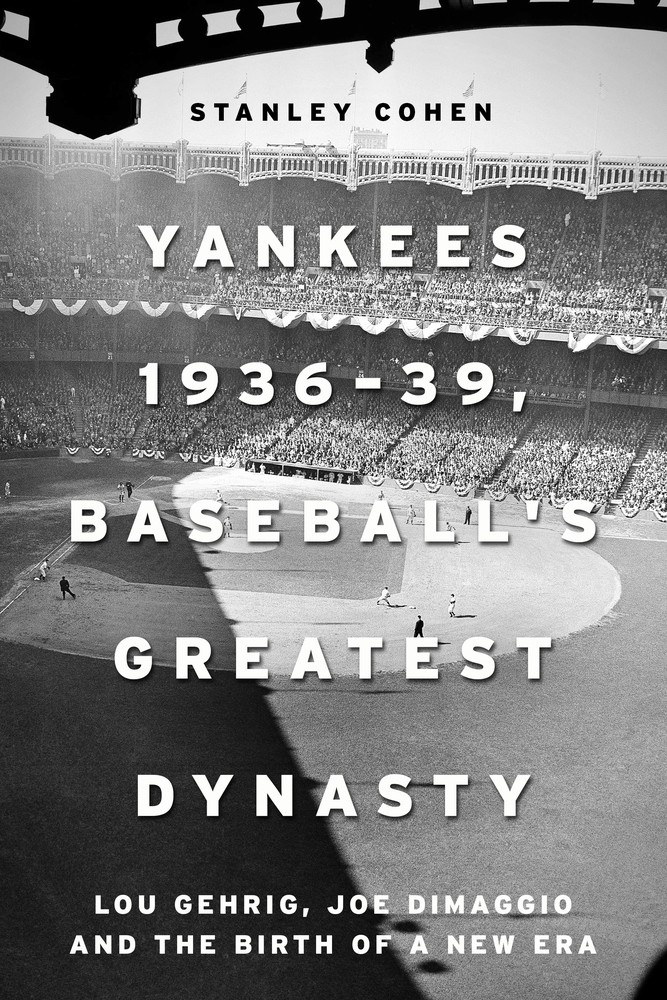

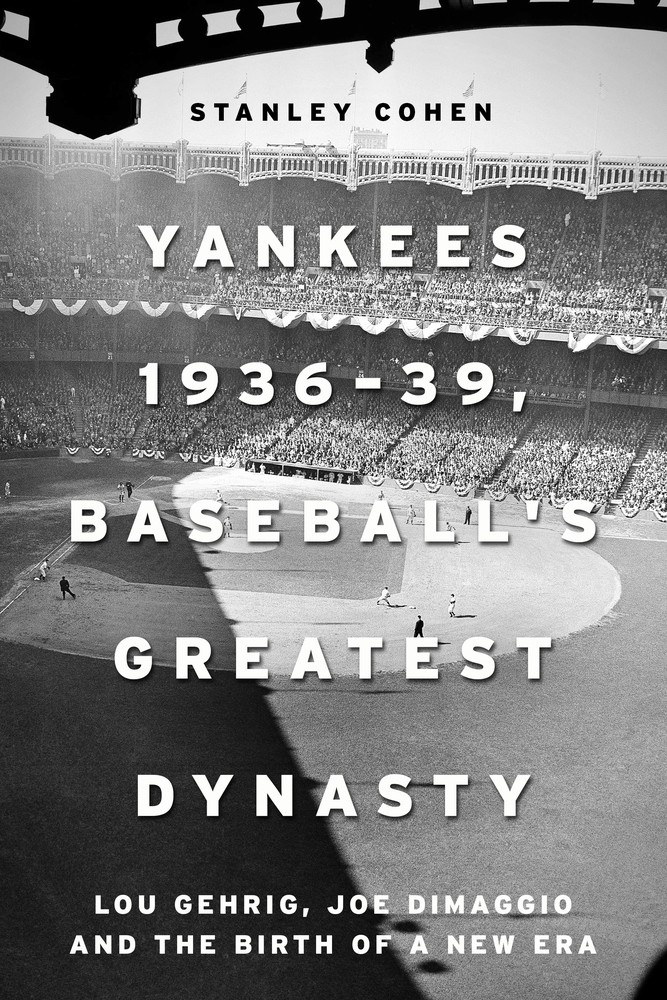

Cover design by Brian Peterson

Cover photo credit: AP Images

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2063-3

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2064-0

Printed in the United States of America

To the Entire Cast

Linda and Greg

Steve and Monique

Michael and Jessica

Sammi and Matt

and, as always,

my co-producer and lifes partner, Betty

Contents

Baseball isnt statistics; its Joe DiMaggio rounding second.

Jimmy Breslin

1936

With Joe DiMaggio in the lineup, the Yankees win their first World Series since 1932, the start of baseballs first true dynasty.

A Savior Arrives from Out of the West

B ack in the day, when baseball was truly the national pastime, the game seemed to reflect the shifts in style and mood that defined its era. It was as if the texture of the sport was sewn into the fabric of its time, its pulse measured beat-for-beat by the events taking place around it.

The Yankees of the 1920s embodied that decade in its every aspect. It was, after all, the Roaring Twentiesthe Jazz Age, when the country bounced to its own tune, full of the snap and sizzle of champagne pop, flappers strutting to the frenzied rhythms of the Charleston, speakeasies humming with a wink and a nod. True to their time, the Yankees of the twenties won with flair and flourish, with an air of superiority that would soon become the logo of the franchise. The dead-ball era was over, and just in time for Babe Ruth to explode upon the scene in a spanking new Yankee Stadium, with its short right-field porch tucked into a cavernous depth that gave it the intimidating aura of a Roman coliseum. The Bambino, who dwarfed everything around him, was the incarnation of the 1920s in both size and performance, a boisterous, fearless Caravaggio who did what he did better than anyone had done it before him.

The Yankees won six pennants during the twenties, the last in 1928, but their reign ended a year later, the year the New York Stock Market crashed and the Great Depression descended upon the nation. The early thirties belonged to the St. Louis Cardinals, a team that became known, appropriately enough, as the Gas House Gang. The Cards were a perfect fit for their time, tough and relentless and without the slightest suggestion of grandeur or majesty. They were a hardscrabble, grind-it-out band that featured the likes of Frankie Frisch, Pepper Martin, Ripper Collins, Joe Medwick, and Leo Durocher who, it was said, gave the team its sobriquet. The Cards, who won pennants in 1930, 31, and 34, often took the field in scruffy, unwashed uniforms, forging an identity with fans who understood the need to make do. They had a ball club that shared the deprivations of the times.

By mid-decade, the times had begun to change. The nation was still in the grip of the depression, but the tide seemed about to turn. Unemployment, as high as 25 percent in 1933, had dipped to 17 percent by 1936. Attendance at Yankee Stadium, which had dropped precipitously in 1934 and 35, rose sharply by almost one-third. It was a time of measured optimism, hopeful but cautious. There was the growing sense that things would eventually right themselves if attention was paid and the work that had to be done was done with dispatch and efficiency. Production rather than style was the key to recovery.

It was a mood that was nutrient for the Yankees of 1936, the rookie year of the incomparable Joe DiMaggio, the start of baseballs greatest dynasty. The Yankees would go on to win four consecutive World Series, and they did it with room to spare. They finished an average of nearly fifteen games ahead of the second-place team. They won their four World Series by an overall margin of 163, sweeping the last two. The 1936 team featured six future Hall of Fame players and a manager that would bring the total to seven. And that was just the beginning. They seemed to improve every year. The 39 team, the last of the dynasty, was, by any measure, the best of them all.

But 1936 was the transformative year; it represented an awakening of sorts. The Yankees had dominated the twenties in devastating fashion. Driven by the power tandem of Ruth and Lou Gehrig, they had won six pennants between 1921 and 28. The 1927 team, considered by many as the best of all time, was known as Murderers Row and for good reason. They won 110 games, finishing nineteen games ahead of the second-place Athletics, and then swept the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. They squeaked through by a narrower margin the following year, their third league championship in a row, and then it all stopped.

In 1929, the Yankees crashed, along with the stock market. They fell into their own depression, albeit briefly, finishing behind Connie Macks Athletics by margins of nineteen, sixteen, and thirteen-and-a-half games from 1929 to 31. They made a brief recovery in 1932, defeating the Chicago Cubs in the World Series, but it was the last of the Ruthian years. His numbers sagged the following season and fell off the charts in 1934, his final year as a Yankee. The Yanks finished second that year, as they had the year before, and began the 1935 season without Ruth in the lineup for the first time since 1919. The power burden fell squarely upon the shoulders of Lou Gehrig, but without Ruth hitting ahead of him, he found himself exposed as the teams only home run threat. He had won the Triple Crown (leading the league in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in) in 1934 but saw his figures tail off a bit a year later. Although a batting average of .329 with 30 homers and 119 RBIs would have been an outstanding season for most players, it was a significant drop from his .363, 49, and 165 the previous year.

Still, the Yankees made a respectable show of it in 1935. The pitching staff, led by Red Ruffing and Lefty Gomez and buttressed by Johnny Allen and Johnny Broaca, compensated somewhat for the power shortage, and the team was in the hunt well into September. They had started the season in good form and led the league in late July, but then the Detroit Tigers, defending league champions, got hot. They put together winning streaks of ten and nine games and slipped past the Yankees into first place on July 26. Detroit stayed hot right on through Labor Day and, on September 8, led the league by ten games. But the Yankees had one last burst left in them. They closed the season winning eight of their last nine games and finished just three lengths off the pace. It was a significant improvement over the previous season when they had ended up seven games in back of Detroit.

Next page