The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Washington, DC

November 27, 1973

I didnt think I was nervous, but I could barely breathe.

President Richard Nixons secretary Rose Mary Woods was on the stand in US District Court demonstrating how she accidentally erased eighteen and a half minutes from a key White House tape in the Watergate casewiping out a conversation between the embattled president and one of his top aides held just three days after the suspicious break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters.

The clunky Uher Universal tape recorder and headphones from Roses White House office sat on the ledge of the witness box. A pedal that let her stop and start the machine with her foot rested on the floor. The bright, high-ceilinged courtroom, its wood-paneled walls burnished with years of crime and punishment, overflowed with lawyers, journalists, and spectators. From the bench, Judge John J. Sirica regarded me with a knowing expression. I felt he saw right through me. My face flushed, broadcasting my youth and vulnerability.

The previous day, Rose had testified that she was in the middle of transcribing the tape from June 20, 1972, when the phone rang at the far end of her desk, and she answered the call while keeping her foot on the pedal. That, she said, must have erased the presidents recorded conversation, replacing it with a steady hum.

I asked her to demonstrate. She pushed the Start button on her machine and placed her sturdy black pump on the pedal. The crowd fell silent as the blank demonstration tape began to whir.

What did you do after the phone rang? I asked her, trying to keep my voice level.

Rose glared at me. At fifty-five, she was nearly twice my age, petite but fierce, dressed that day in a color-blocked turquoise, chartreuse, and orange sheath topped with a strand of pearls. A gold cross glinted from a ring on her right hand. I had to take those off first, she said in a hostile tone, delicately pointing to the headphones resting on the ledge. With that slight movement of her fingers, her foot lifted from the pedal.

The tape stopped cold.

Even if shed mistakenly pushed Record instead of Stop, releasing the foot pedal when she answered the phone would have halted the tape and there would be no eighteen-and-a-half-minute gap.

Rose had lied, and I had caught her.

The crowd gasped and a tsunami of journalists rushed from the courtroom, headed for the bank of pay phones in the hall.

That it worked when she did it that way in her office, Rose stammered.

Then maybe we should continue the demonstration in your office, I proposed. Amazingly, neither her lawyer nor those representing President Nixon objected to this suggestion.

In the five and a half months leading up to this day, Id been working sixteen-hour stints as one of three trial lawyersand the only womanon the Watergate special prosecutors obstruction of justice and cover-up task force. We were investigating whether Nixon and his closest aides had obstructed the investigation of the June 17, 1972, break-in at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the elegant Watergate complex in DCs Foggy Bottom neighborhood. Five burglars, the man who recruited them, and the mastermind had been caught, and their connection to the White House and Nixons Committee to Re-elect the President had been made clear by the sleuthing of the Washington Posts Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, by Judge Siricas persistent questioning during the burglary trial, by the US Senate probe of the scandal that had been underway since May, and by our work.

Roses testimony was the culmination of an astonishing battle in the courts. Just four months earlier, we and the nation learned that Nixon had secretly taped every conversation in the Oval Office and his ancillary office in the nearby Executive Office Building. We immediately subpoenaed nine tapes that we believed, on the basis of White House calendars and visitor logs, as well as grand jury testimony, included discussion of the Watergate break-in. Nixon stonewalled turning over the tapes until October, when public outrage forced him to acquiesce. A week after agreeing to give us the tapes, however, his lawyers stunned us with a claim that two were missing. A wary Judge Sirica ordered a public hearing that ended with an order for Nixon to deliver the seven tapes that he acknowledged having in his possession. Soon afterward, before we received any of the tapes, Nixons lawyers revealed a problem in a third tape, the one from June 20 that recorded a conversation between the president and his chief of staff, H. R. Bob Haldeman, three days after the break-in. For eighteen minutes and thirty seconds of that conversation, the tape simply buzzed and clicked.

Unlocking the mystery of that gap was the reason for Rose Mary Woodss testimony today. The White House said there was no innocent explanation and that only Rose could answer for the gap.

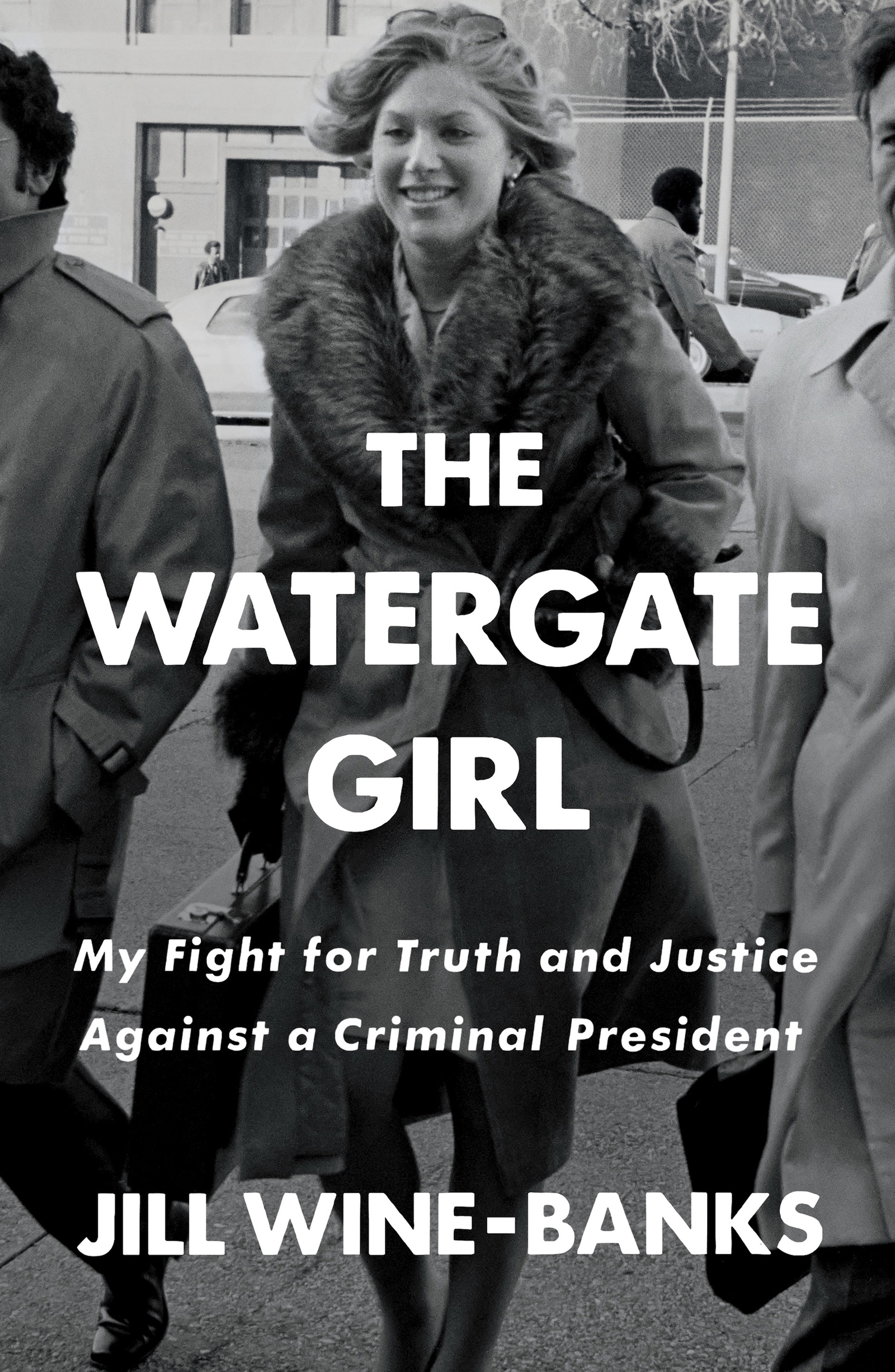

After court adjourned, I took a taxi to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue to see Rose demonstrate her testimony one more time, without a court reporter and with only the White House photographer to record it. In Roses office, I was astounded to see a large crowd, including a gaggle of lawyers, the wife of one of Roses lawyers, and a friend of Roses from New York who was identified simply as Miss Val. The White House photographer snapped Rose as she contorted her body to reach the phone at one end of her desk while holding down the foot pedal of her tape recorder at the other end with her left foot. It was a tortuous position that would have been impossible to maintain for one minute, let alone for eighteen. Forever afterward it would be derisively known as the Rose Mary Stretch.

If there were any doubts that Rose had lied earlier in court, the pictures laid them to rest. And yet I felt sorry for her. When the image of her ridiculous stretch was spread across Americas front pages and mocked in editorial cartoons in the following days, Rose became the butt of a national joke. I saw something of myself in the presidents trim, copper-haired secretary, in the way wed both had to survive in a world of men whod often bullied and belittled us.

I felt sympathy for her, too, because the president had abandoned her. He let her be blamed for the eighteen-and-a-half-minute gap.

My picture also was in the papers the next morning, smiling in my miniskirt and tall boots as I hailed a taxi outside the White House after Roses demonstration. But the flush of success caught by the photographers vanished when I arrived home late that night. As soon as I left the garage behind my brick town house on 20th Street NW, I saw the back door ajar. A cold fear spread through my body, but, as is typical for me, I didnt hesitate to walk into a potentially dangerous situation. I entered the kitchen, picked up the phone, and called the police. As soon as they arrived, I searched the house. Some canceled checks were missing from the antique desk in the basement, as was a safety deposit key that I kept in an unlocked metal box. Upstairs, a new green velvet pantsuit Id laid out on the bed had vanished, along with a few inexpensive baubles from my dresser. In a panic now, I ran to the attic, where I had stashed copies of documents from the Watergate investigation in a brown cardboard box, a hedge against our office being shut down. The documents were exactly where Id left them. Relieved, I spoke to the police.