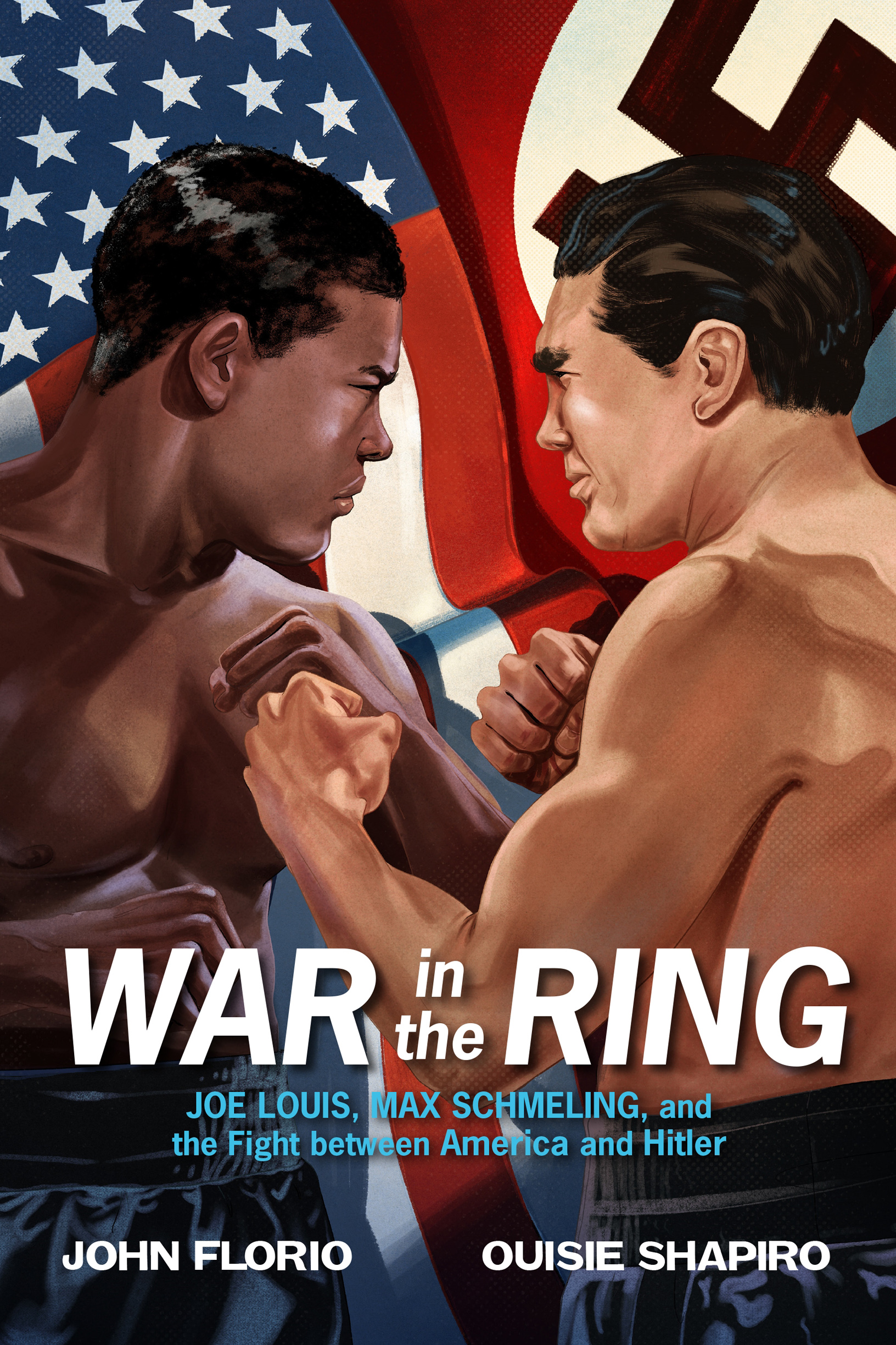

Americas got the jitters. Its all over the news that German Chancellor Adolf Hitlers army has taken Austria without a fight and is threatening to conquer other countries in Eastern Europe. Hitler is spreading his hatred of Jews; his Nazi party is taking prisoners and herding them to concentration camps. The headlines are scary.

The United States wants no part of Germany, the Nazis, or a global war.

At ten oclock, New York time, the eyes of the world turn to a boxing ring in Yankee Stadium. There, the heavyweight champion of the world, a twenty-four-year-old black American named Joe Louis, is about to defend his title against a thirty-two-year-old white German, Max Schmeling.

As the two fighters climb through the ropes, the overhead lights beaming down on them, men and women across the United States lean in to their radios, hanging on the outcome.

In Germany, its the middle of the night, but millions of residents have their lights on and their radios tuned to the broadcast coming over the phone lines.

The bell rings.

Louis moves to the center of the ring, his gloves raised. Schmeling does the same. Each carries the weight of his country on his back.

Eighty thousand fans in the stadium hold their breath.

Seventy million more press their ears to the radio.

This is it.

This is the war in the ring.

America was in the midst of the Great Depression. The stock market had crashed two years earlier, and the slowdown was so severe that even the banks couldnt survive. Nearly ten thousand were on their way to shutting down, taking with them the life savings of millions of Americans. Billions of dollars evaporated. Countless businesses collapsed. People waited in long lines for bread or sought out charity kitchens for soup. The poorest of the poor, having lost their homes along with their money, pitched tents in local parks and slept outside.

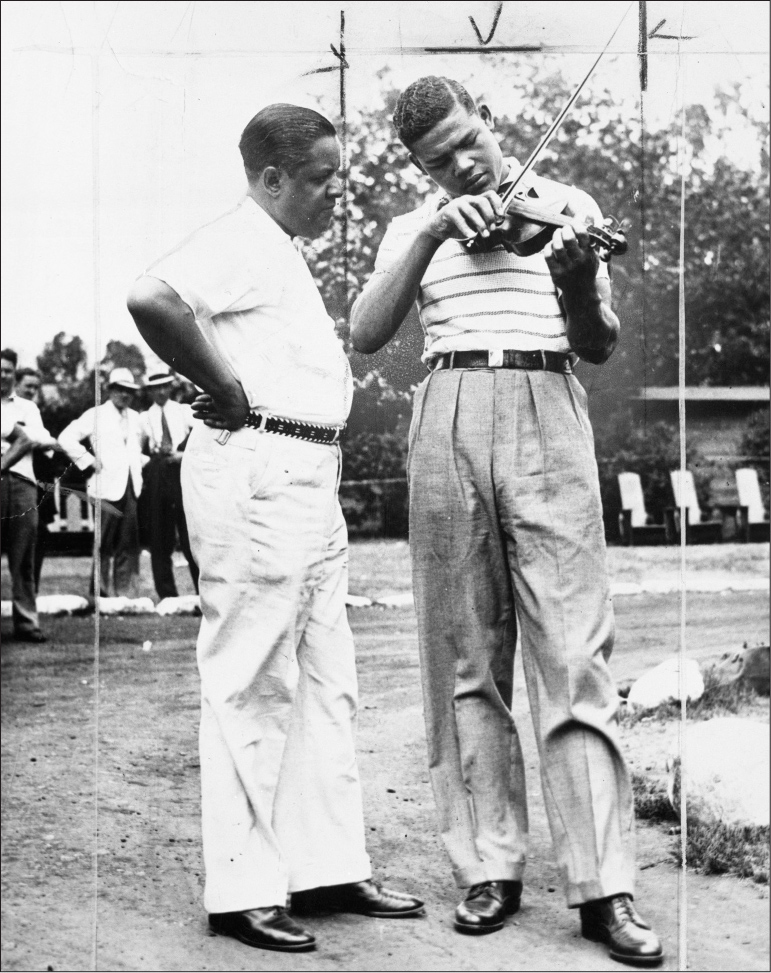

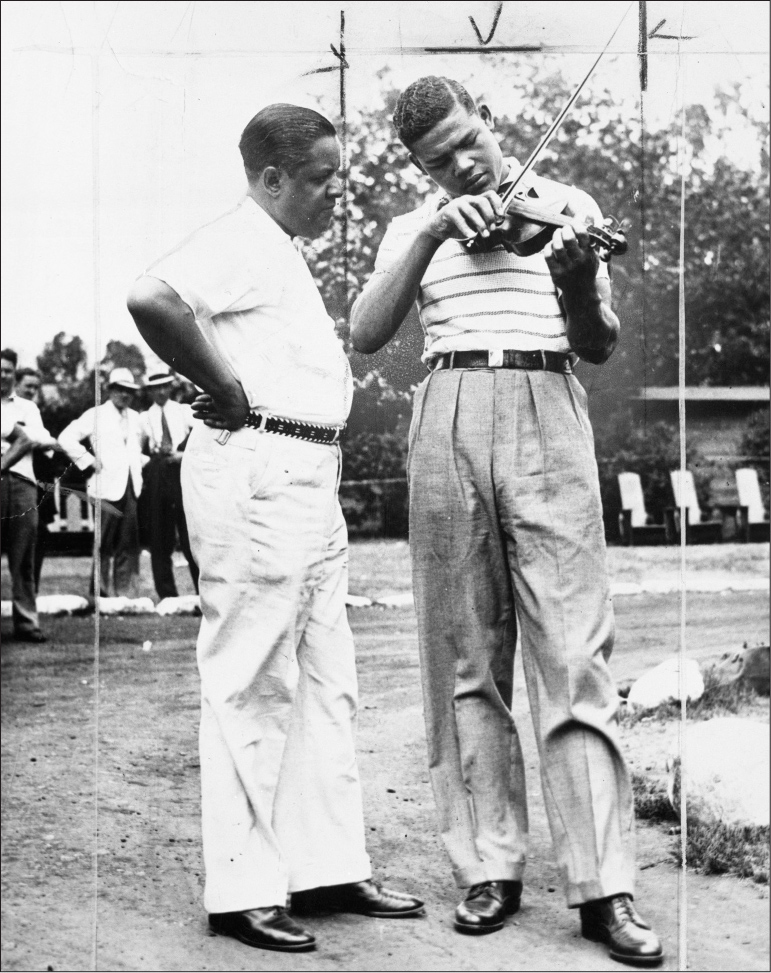

In Detroit, the home of the nations car industry, seventeen-year-old Joe Louis Barrow was on his way to school, his hand-me-down clothes barely fitting his six-foot frame. Like virtually every kid in the neighborhood, Joe had nothing in his pockets. But unlike the others, he had a musical instrument under his arm.

Here I was, Joe later said, big as a light heavyweight, going to Bronson Vocational School, carrying this little bit of a violin. You can imagine the kidding I had to take. I remember one time some guy called me a sissy when he saw me with the violin, and I broke it over his head.

After the stock market crash, Americans line up for free food.

Joes friend Thurston McKinney was fighting his way through the amateur ranks as a lightweight boxer. He suggested that Joe ditch the violin and join him in the ring. After all, there was big money to be made in boxing, and not a penny to be had in playing a stringed instrument. Just look at the heavyweight champ, Jack Dempsey, Thurston said. He retired four years ago, and hes still loaded. Joe wasnt sold on the idea, mostly because he knew how hard his mother worked to pay for his violin lessons.

A young Joe Louis Barrow practices the violin.

As a small boy growing up in Alabama, Joe had been a quiet kid. While his brothers and sisters were outside playing, or picking cotton on the family patch, he would wander down to the nearby swamp and hunt snakes.

Joes parents, Lillie Reese and Munroe Barrow, were the children of former enslaved people and worked as sharecroppers outside the town of LaFayette. Joe was the seventh of eight children, living in a shack with a sagging roof and loose floorboards. It looked like a good wind would have blown it down, he said years later.

The strain of supporting a large family with the backbreaking work of picking cotton day in and day out landed Munroe in a psychiatric hospital when Joe was just two. Lillie was left to raise the children by herself for a few years until she married Pat Brooks, a widower with eight children of his own.

Joe fed the chickens and the hogs, and when he was old enough, joined the rest of his family under the blazing sun in the fields, bent over at the waist, dragging a seventy-pound sack of cotton behind him. At night he went to bed complaining about having to sleep in the same bed with two of his brothers.

The Barrow-Brooks clan was no different from hundreds of thousands of other struggling black families in the South. Joes family was accustomed to the hard life in Alabama, but they heard that better-paying jobs could be found in the bustling cities up north. And when word got out that the Ford Motor Company in Detroit was paying as much as $7 a day to work in its factoriesmore than twice what sharecropping paidPat figured it was worth a shot. How could things be any worse in Detroit than they were in Alabama? At least there would be electricity and indoor plumbing, two luxuries theyd never had in the South. And so by 1926, Joe and his family were settled in Detroit and Pat was working at Ford.

The Barrow-Brooks family was part of the Great Migration that saw more than a million-and-a-half African Americans leave the South and move north and west in search of jobs and safety from violent threats, most of them coming from white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan. A second wave would follow twenty years later, taking more than five million African Americans with it.

Even in booming Detroit, however, all was not rosy for black residents. As African Americans poured into the city, its color line grew more restrictive, forcing blacks to live in certain neighborhoods. Joes family found housing in Black Bottom, the east side neighborhood named by 18th-century French explorers for the rich, black soil that had once been farmland. Block after block was lined with shops, schools, churches, bars, and pool halls, and the area offered a thriving nightlife of musicians and entertainers. Many of the homes were tenements that had been built quickly to accommodate the mass influx of Southern blacks.

A few years after moving to Detroit, Pat was out of work, having lost his job at the Ford plant when the stock market crashed in October 1929. It was all he and Lillie could do to hold on to their tenement.

Joes friend Thurston kept pushing the fight game. Youre a big, strong guy, he told Joe. If you stick with it, youre sure to rake in more money than any fiddler would dream of earning. Besides, he said, You got to have education to be a good one on the violin. You got to read notes. Thurston had a point: Joe had no interest in learning music, and it would take years before he could develop his skills. Joe figured that he could learn how to box now and, if he was good at it, earn some money to help his family buy groceries.