All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner

whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of

brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address

Bloomsbury USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA HAS BEEN APPLIED FOR.

First U.S. Edition 2008

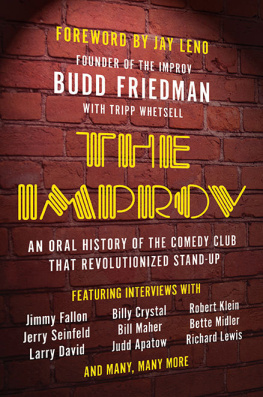

In the mid-1970s, when I was a freelance writer living in Greenwich Village, the Improvisation was, pound for pound, the best entertainment value in New York. At this bare-bones, storefront club on the seedy western edge of the theater district, for a few bucks' cover charge and a couple of drinks, you could sit for an entire evening, well into the wee hours, and watch stand-up comedians virtually nonstop. Most were young and unknown; many weren't very good. But a few of them were terrific, and an evening at the Improv always had the excitement of discovery, of getting an insider's early look at the innovators in an art form that seemed to be changing before your eyes.

First times are always the best, and at mine (early in 1975, as best I can figure) the highlight was a trio of comics whom I remember as if they were murderers' row in a 1930s All-Star Game. First came Ed Bluestone, a dour, brainy monologuist who did wry, deadpan wisecracks about his Jewish upbringing. (The only line I can recallabout his Sunday school lessons in Jewish history that played like a weekly soap opera"Bam! The Jews are enslaved by rabbits!"). He was followed by Richard Lewis, a lean, jittery young comic whose own brand of Jewish angst took the form of nervous pacing and tortured run-on sentences that caught the audience up in the kind of rolling, rhythmic laughter that comedians like to compare to waves crashing onshore. Finally, there was a soft-looking, glassy-eyed weirdo whom I had encountered earlier in the eveningwhen he barged ahead of a few of us waiting in line at the Improv's tiny restroom, located all too conspicuously in the hallway between the bar and the showroom. He had a pipsqueak voice with a vaguely Eastern European accent, and on stage he nervously told bad jokes, lip-synched to a recording of Mighty Mouse's theme song, and then, just to cross everybody up, did an impression of Elvis that blew the house away. A few months later I saw Andy Kaufman for the second time, on the premiere of Saturday Night Live.

Those days now seem both far away and oddly current. After springing up in the 1970s, enjoying a nationwide boom in the '80s, and falling on hard times in the '90s, the comedy clubs are back. New York City alone, as I write this, has nearly a dozencompared with just three in their '70s heyday. But the sense of adventure has been replaced by the programmed predictability of a General Motors assembly plant. The comics all sound pretty much alike these days, with the same patter to loosen up the crowd ("Anyone from out of town?"in thirty years no one has come up with a better icebreaker), the same recyclable loop of stand-up topics (sex, New York subways, commercials for Viagra). On weekend evenings, the clubs typically squeeze in three shows, spaced an unforgiving two hours apart: four or five comics, two drinks and the check, and you're out the door in ninety minutes flat. When I took out a pen at one club on a recent Saturday night to make some notes on a comic doing pretty good impressions of Bill Cosby and Dr. Phil, a bouncer suddenly appeared in front of me, ordered me out of the room, and read me the riot act: no note taking without the prior consent of the management and the comics. Just when did the fun go out of stand-up comedy?

For me, and so many others growing up in the baby boom years, stand up comedy wasn't just fun; it was an obsession. I organized my homework around the stand-up comedians on The Ed Sullivan Show and the other TV variety shows that filled so many of the prime-time hours in the 1960s. I communed with them in private on the all-but-forgotten medium of long-playing records. So intent was I on savoring my first comedy albumBill Dana as Jose Jimenezthat I held off listening to the entire record in one sitting, saving the B-side for a day just to extend the pleasure. Later came Bob Newhart and Bill Cosby and the Smothers Brothers; collections of Stan Freberg's great song parodies; the novelty hits of the early '60s like My Son, the Folksinger and The First Family.

Beginning in the late 1960s, however, stand-up comedy began to change. It became somehow more essential. It seemed smarter and more current, and it connected more directly with my generation and the things we talked and cared about. And much of that change was inspired, I realized only many years later, by a comedian whom most middle-American kids like me didn't have in their record collection: Lenny Bruce.

Like Bruce, the comedian-cum-social commentator who challenged the guardians of public morality and died of a drug overdose in 1966, stand-up comedians who reached their artistic maturity in the late '60s and '70s saw themselves as rebel artists. Unlike the comedians of an earlier generationwho, for the most part, told jokes written by othersthey wrote their own material and used it to express their personal point of view about what was happening in the country, the culture, and their own lives. They both reflected and helped define the ethos of the counterculture as surely as the troubadours of rock or the protest leaders of the left. They took aim at political corruption and corporate greed, made fun of society's hypocrisy and consumerist excess, mocked the button-down conformity of Eisenhower-era America. By their very presence on stagealone in front of a mike, telling it like it isthey were advertisements for honesty and authenticity, a rebuke to the phoniness and self-righteousness of your parents' generation. Except when they themselves were phony and self-righteousand then, of course, they were making fun of that, satire of a more devious sort.

They became fixtures in America's living rooms on prime-time variety shows and late-night talk shows, and later they helped pioneer the young medium of cable TV. They released best-selling record albums and drew rock-star-like crowds in arenas and concert halls. They spoke to a new generation, the baby boomers who had grown up with television and the cold war and now jammed into comedy clubs on date night (better than going to a movieyou could talk to each other during the show), finding kindred spirits in these writer-performers who articulated their own political disaffection, social concerns, sexual anxieties, and bad-date experiences. Their voice continues to resonate in the national conversation, from the monologues of late-night TV hosts to the insta-punditry and parodies of the Internet. Their point of viewironic, skeptical, media savvy, challenging authority, puncturing pretension, telling uncomfortable truthsis the lens through which we view everything from presidential politics and celebrity scandal to the little trials of our everyday lives.