M OST BOOKS ARE COLLABORATIVE EFFORTS, AND THIS one is no exception.

The list of thanks should start with the Rocky Mountain News and The Denver Post and the beat work over the years of Rick Morrissey, Steve Caulk, T.J. Simers, Butch Brooks, Sam Adams, Adam Schefter, Jim Armstrong, Joseph Sanchez, John Henderson, Tom Kensler, Michael Knisley, and others. Im also indebted to Bob Kravitz, Norm Clarke, Mark Wolf, Jay Mariotti, Woody Paige, Mark Kizla and Dick Connor. I trust Ive kept their reporting and commentary in perspective.

Id also like to thank my editors at the Rocky Mountain News, including Barry Forbis, who allowed me the freedom to complete this project, and Jim Saccomano, the Broncos director of media relations, and his assistants, Paul Kirk and Richard Stewart.

Id be remiss not to credit Sports Illustrated, Sport, Football Digest, Beckett Football Monthly, Newsweek, The Bremerton Sun and other publications too numerous to mention.

Thanks also to several illuminating books, including The Quarterbacks by Mickey Herskowitz, The Pro Football Chronicle by Dan Daly and Bob ODonnell, Great Ones by Beau Riffenburgh and David Boss, War Stories from the Field by Joseph Hession and Kevin Lynch, Super Bowl Chronicles by Jerry Green, John Elway by Mark Stewart, Orange Madness by Woody Paige and The Color Orange by Russell Martin.

Im especially indebted to Roland Lazenby as well as the people at Addax Publishing, including Darcie Kidson and Bob Snodgrass, whose patience and professional insights were invaluable.

My wife, Loraine, however, gets the first-place medal for patience.

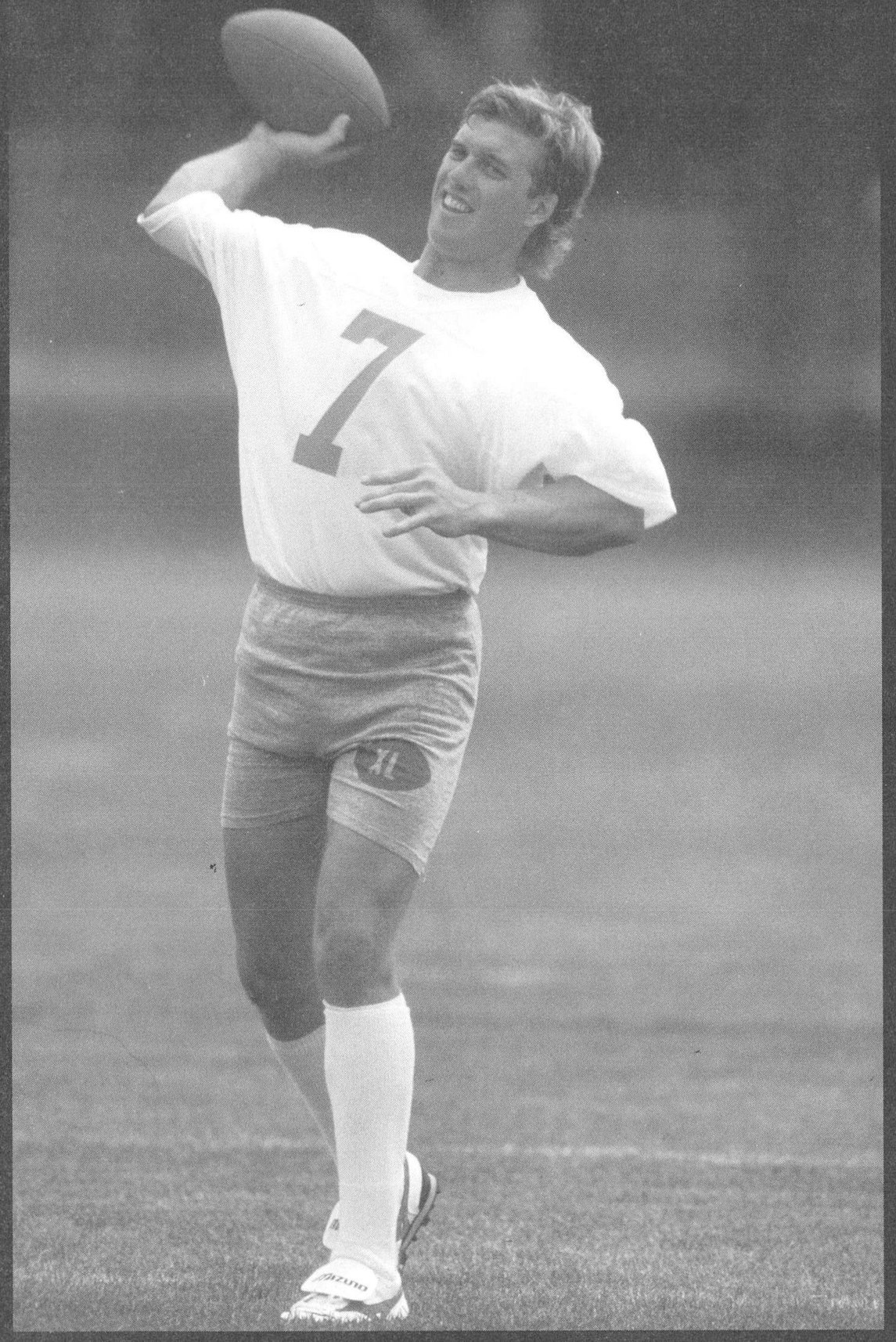

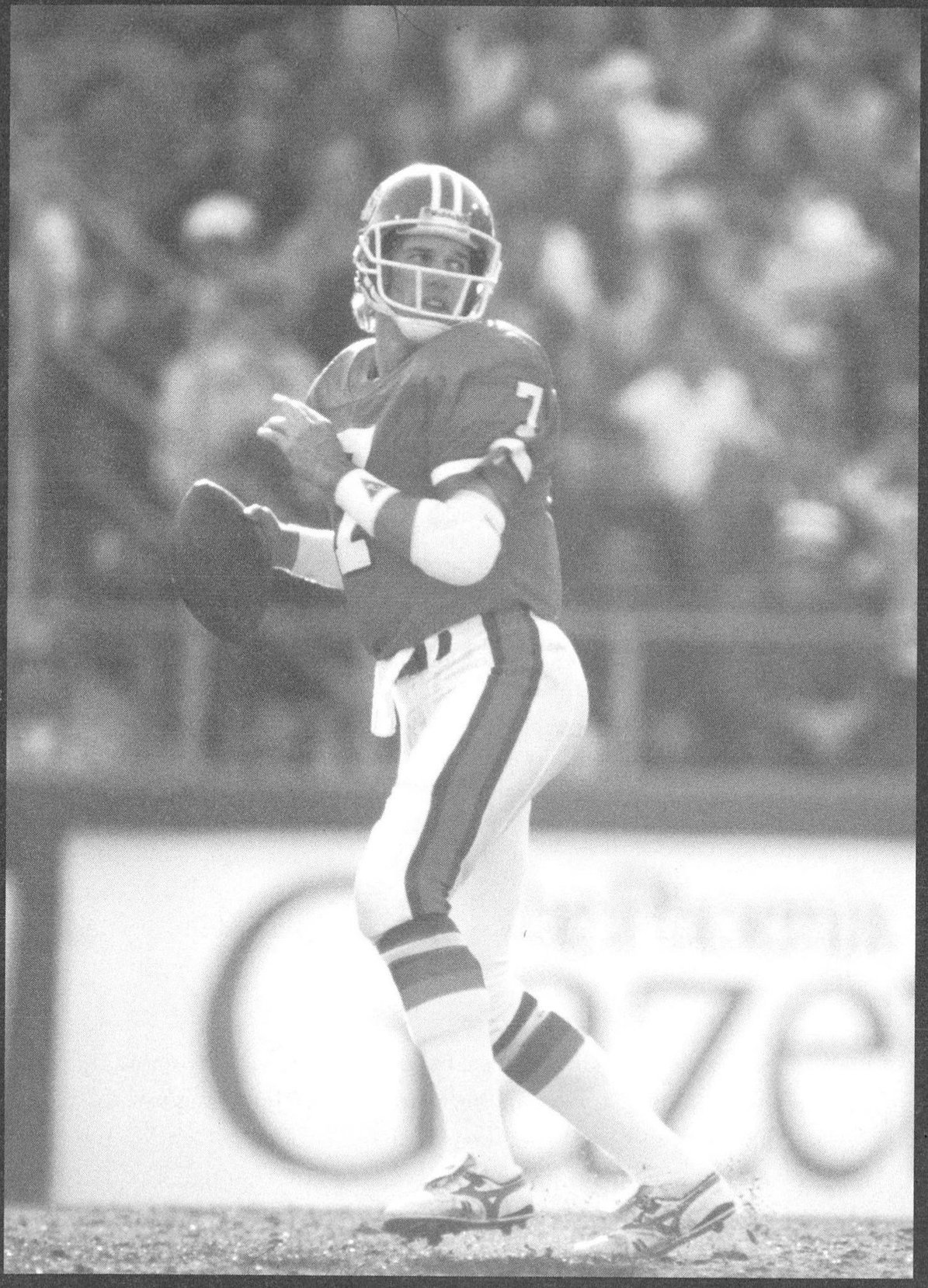

Elway can throw a football 40 yards at bullet speed and 60 yards with cross-hair accuracy. One of his passes tore the flesh off a finger of a Stanford receiver, exposing the bone.

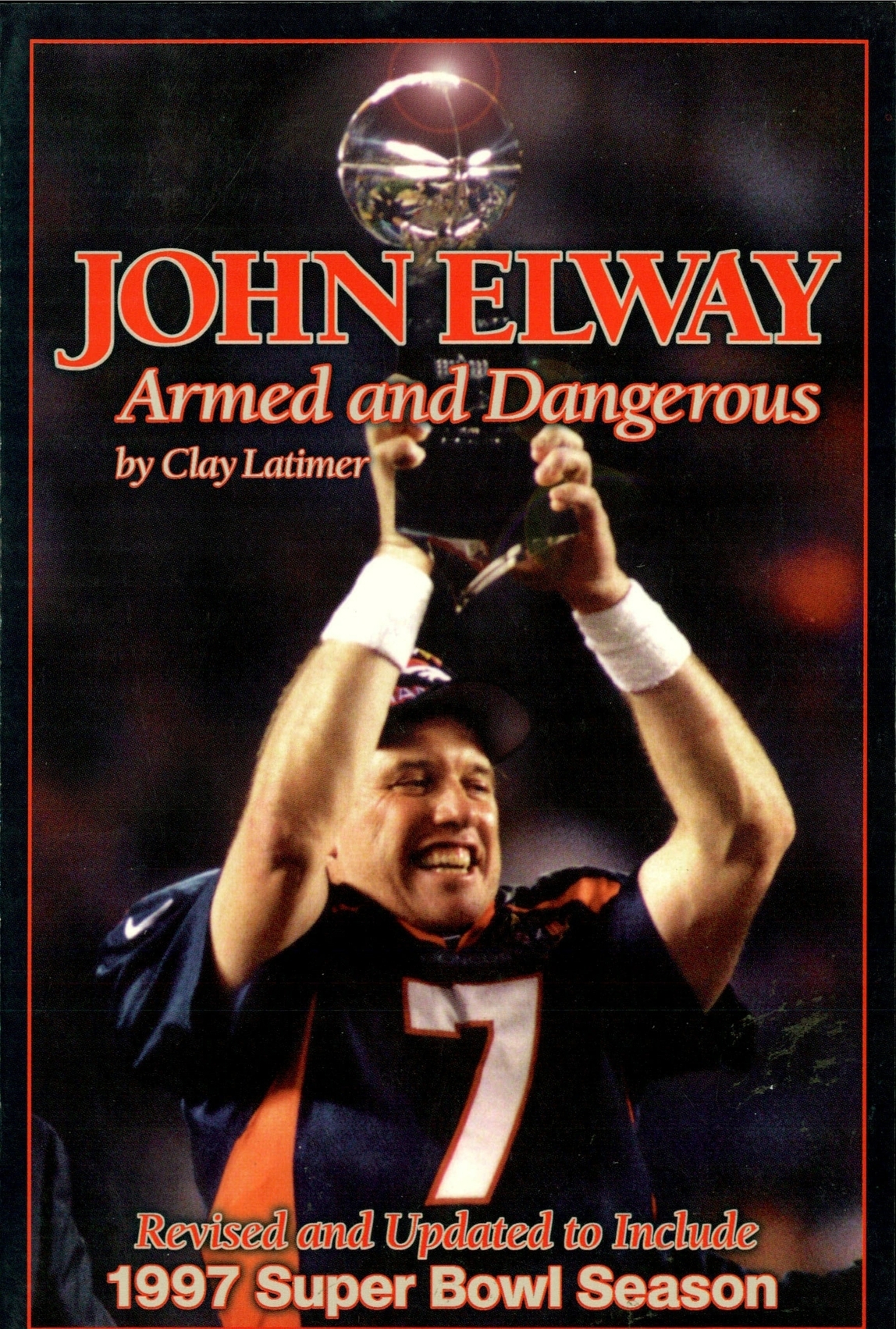

Chapter One

The Arm

A FTER A GLOOMY DEFEAT IN 1995, THE DENVER BRONCOS had nothing left to do but count the bodies. The injuries had been piling up for weeks, and even John Elway sounded as if he might become a casualty of another dying season.

In a weary monotone following a loss to the Kansas City Chiefs, which kept the team out of the playoffs for the second consecutive season, the graying, ashen-faced quarterback talked openly about retirement.

Eventually, however, Elway was stopped in his tracks by one of the NFLs most durable and enduring legends: himself.

Although his numbers already made him suitable for framing in Canton, Ohio, Elway decided to continue to play the game of his life. Before hes finished, Elway hopes to pass and run for more yardage than any quarterback in NFL history, including Johnny Unitas, Dan Marino, Fran Tarkenton, Joe Montana, and Bobby Layne, one of Elways enduring role models.

During the past two decades, Elway has gone from blue jeans to power ties, frat boy to international icon, All-American letterman to filigreed businessman. But on the field, hes still the same ol John, burning with timeless passion to run and pass and tackle any obstacle that stands in the way of winning, even if it means diving headfirst into a muddy end zone or lifting his fist in defense of a fallen buddy.

In an era of bejeweled narcissists and baleful outlaws, Elway is a football fundamentalist who missed only 10 starts in his first 14 seasons because of injuries; won more games than any starter in NFL history; led the Broncos out of the pocket of doom to victory with innumerable fourth quarter, game-saving drives; and, in an era of wandering stars, played in one city for one team, like the passing stars of old.

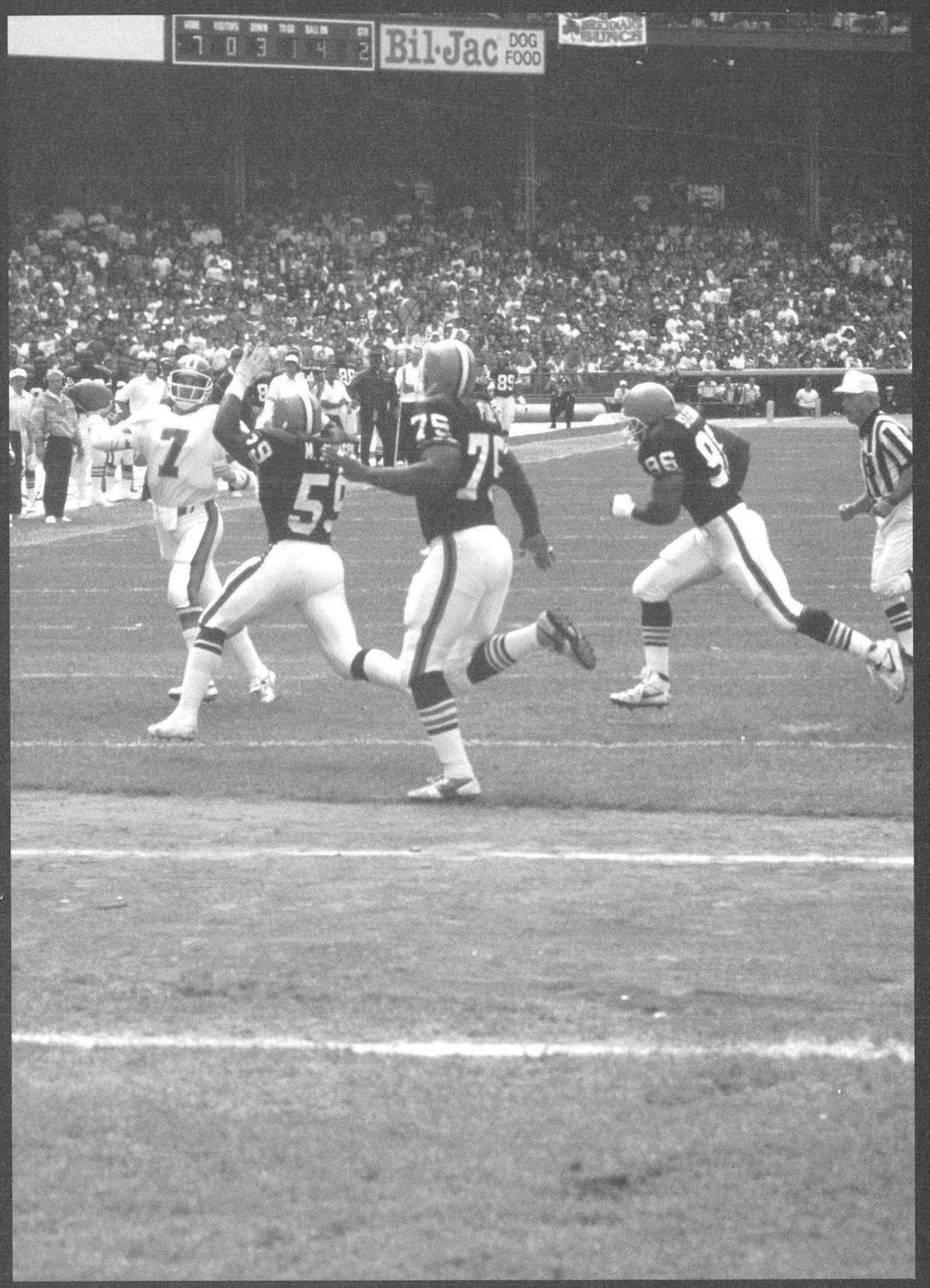

Elway is a defenses worst nightmare when hes on the run, scanning the field for a receiver. He was the only quarterback we were ever told not to chase from the pocket, said former Cleveland and Oakland defensive lineman Bob Golic.

Moreover, Elway has survived countless surgeries, hundreds of sacks, a controversial showdown with the NFL, a harrowing rookie season, three humiliating Super Bowl defeats, devoted critics, the withering burden of a coach (Dan Reeves) with whom he couldnt communicate, as well as his own ruthless perfectionism.

But Elway armed himself for the long run with the loyal help of his father, a college coach, and his own right arm, which just happens to be the most dangerous in the games history.

John Elway is the Michael Jordan of the NFL, Joe Theisman said. You expect every one of Jordans shots to go in the basket and you expect every one of Johns passes to be something special.

Added Joe Namath: Everyone should realize that John is special. We might not have seen anyone quite like him before.

Elways arm doesnt look that powerful.

Its 34 inches long. The biceps are a modest 12 inches unflexed. The forearm is unformidable looking. The wrist is inconspicuous. The hand could belong to an average quarterback.

But only Elway can throw a football 40 yards at bullet speed, 60 yards with cross-hair accuracy, 70 yards with a tight spiral while backpedaling and 80 yards on a powerful whim. Only Elway can fire a 66 mph fireball, 50 yards downfield and 30 cross-field; or tear the flesh off a receivers finger; or stamp an X on a receivers chest with the point of the ball.

All great quarterbacks have signature assets. Joe Montana was the master of timing and precision. John Unitas had perfect form; Sonny Jurgensen was the best pure passer; no one could see the field better than Dan Fouts; Dan Marino has the quickest release since Joe Namath; Bobby Layne threw an ugly pass but won nonetheless.

Elway?

His arm is his destiny.

Its carried him through good times, bad times and mad times on fields richly grained with history and ancient blood and to AFC Championships, Super Bowls and hundreds of NFL and college games.

Elways signature play is the one in which he sprints to one sideline, stops, scans, pivots, and then throws a rope to the far side. I used to strain every muscle in my body to throw 70 yards, and he stands there and flicks his wrist, former Cleveland Browns great Otto Graham said.

Its enabled him to pass for tens of thousands of yards and hundreds of touchdowns in the NFL, to break defenses into ungatherable fragments, to make hyperbole plausible for normally underwhelmed critics.

It was generations in the making, too.

Johns grandfather, Harry Elway, quarterbacked a 1908 Pennsylvania team that played against Jim Thorpe, one of the centurys greatest athletes. Johns father, Jack Elway, was a star freshman quarterback at Washington State, before an injury ended his career.

He passed his skills to his son, who passed em into history.

Ive been blessed with a gift from God for throwing a football, John said.

In high school, Johns knee almost buckled and snapped during the first half of a Friday night game. At halftime, he was forced to limp to the dressing room. But after a doctor wrapped his knee, Elway headed right back into the action.

In the second half, Elway hopped to his left on a roll-out, which bought him enough time to locate a receiver streaking to the end zone 60 yards away.