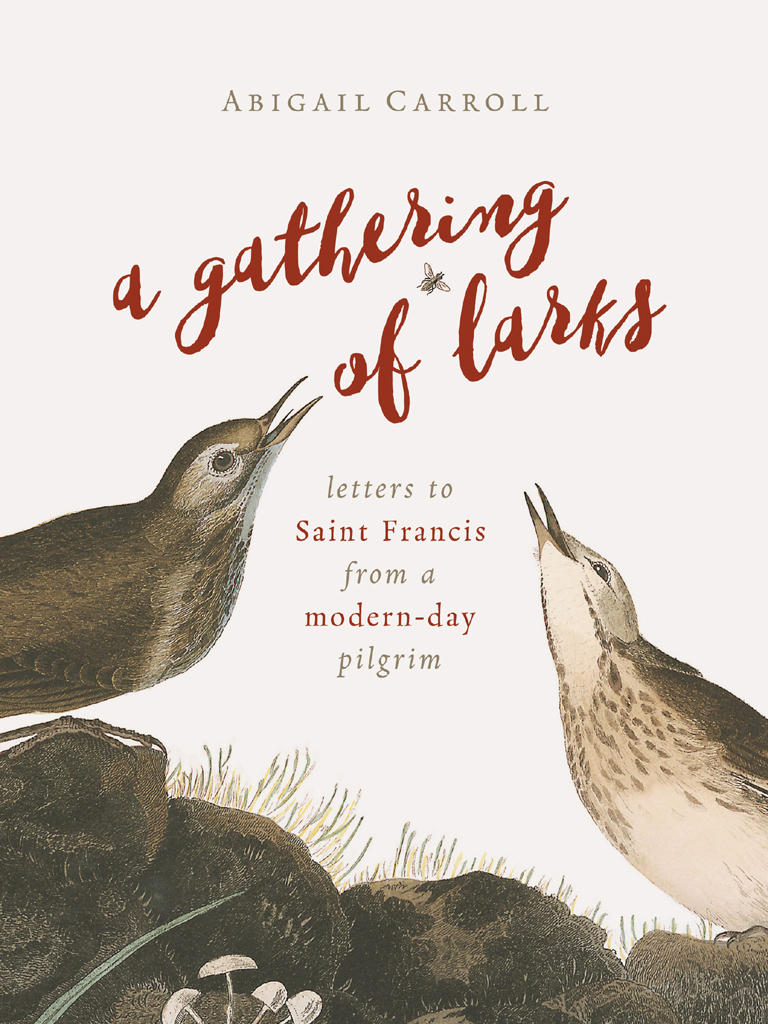

A Gathering of Larks Letters to Saint Francis from a Modern-Day Pilgrim ABIGAIL CARROLL WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 www.eerdmans.com 2017 Abigail Carroll All rights reserved Published 2017 22 21 20 19 18 171 2 3 4 5 6 7 ISBN 978-0-8028-7445-0 eISBN 978-1-4674-4683-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Dedication For my fellow modern-day pilgrims

Jennifer Decker, Deborah Dickerson,

Kevin Fitton, Leigh Harder, and Manisha Munshi,

whose keen, encouraging feedback has strengthened

this book and whose gift of friendship

has gladdened my journey.

Contents A letter bridges distance.

It travels roads, crosses borders, and traverses mountain ranges and oceans, carrying the wordsand a bit of the heartof the letter-writer. The letters in this book also bridge distance, but of a different kind. They travel across time, reaching out to a figure whose life was framed by cobblestone streets, feudalism, lepers bells, troubadours, woolen tunics, wood smoke, minstrels lutes, and crusaders swords. Francesco Bernardone, the man who would become famous as Saint Francis of Assisi, inhabited a wholly different world than the one we live in, and yet the echo of his fascinating, at times beguiling, twelfth-century life reverberates through the centuries and speaks to us today. While many people feel an affinity for Francis all these centuries later, a thick shroud of romanticism threatens to replace the man with the myth. For most of my life, the St.

Francis I have encountered has been as garden statuary, prayer card images, childrens book illustrations, and stained-glass windows. In these letters, I attempt to bridge the distance between who Francesco Bernardone really was and who we have made him to be. Each letter is an invitation bidding the life of this holy man from Assisi to speak for itself. Together, they probe his humanness, poke fun at the sentimentality surrounding his persona, and attempt to parse man and saintgetting under his halo, so to speak. If these letters manage to do that, as I hope they do, the point is less to challenge than to inquire. This is not the correspondence of an adversary or a cynic, but of one who is reverently, if candidly, curiousa modern-day pilgrim in search of a friend with whom to share the journey.

A friend rejoices with you when you rejoice, weeps with you when you mourn, and cares to know what is on your heart and mind. Likewise, I have cared to know what was on Francescos heart and mind when he wandered the fields of Umbria, kissed a leper, heard a crucifix speak, stole from his father to restore a crumbling church, parted with his clothes in the public square, walked to Rome barefoot, scissored Clares locks with a tender hand, attempted to single-handedly halt the Fifth Crusade, tamed a ferocious wolf, underwent failed surgery on his eyes, received the stigmata on Mount Alverna, penned poems and songs that we still sing today, and died lying naked on the dusty Umbrian earth. In these letters, I explore the spiritual landscape of Franciss life, and, as with a close friend, I invite him into the spiritual landscape of mine. By sharing with Francis my joys, hopes, questions, and doubts, these letters bridge yet another distance: the vast canyon between the head and the heart. The Swedish diplomat Dag Hammarskjld famously said, The longest journey of any person is the journey inward. How do we embark on that journey? Prayer and contemplation come to mindstudy and reflection as well.

Indeed, all manner of spiritual disciplines may help. But a simple conversation with a fellow pilgrim is often all the encouragement we need to set out on that journey, or to invigorate our step. I am thankful for those fellow pilgrims, like Francis, who have gone ahead of me and whose storied lives inspire my faith. Francesco Bernardone was born to a wealthy Italian cloth merchant in Assisi in 1181 or 1182. His mother, Pica, baptized him John while his father was away acquiring fabrics in France, but upon returning, his father changed the name to Francesco, a choice that expressed the cultural and business promise of France in their lives. The new name would suit the young Italian well, but for reasons other than his fathers, as Francesco took up the life of a French troubadoursinging, reciting poetry, drinking, and making merry.

His friends dubbed him King of the Revels, and wherever he went, he was the life of the party. When he spent a year in a Perugian dungeon as a prisoner of war and became chronically ill, fellow prisoners remarked that his sense of humor remained strong and helped buoy others spirits. While Francis was a natural businessman and would have succeeded in the cloth trade, he chose instead to pursue the glories of knighthood and, with his familys blessing and a fine suit of armor, set off to join the Fourth Crusade. However, a powerful but enigmatic dream his first night on the road put a halt to his plans. In the dream, a voice summoned Francis to return to Assisi, and, when he did, he suffered the humiliation of being seen as a coward. Unable to focus, he wandered the countryside.

He also visited Rome at this time, though whether as pilgrim or sightseer is uncertain. At the Vatican, he was so appalled by the pittance that visitors were throwing on Saint Peters tomb that he reached deep into his purse and flung a lavish number of coins through the confessio grate, the sound of which caught the attention of many astonished bystanders. Both in Rome and Assisi, Francis gave liberally (some would say recklessly) to the poor, but he deeply loathed leperstheir deformities, their stench, their rags. One day when he unexpectedly encountered a leper on a long walk in the plains below Assisi, something inside Francesco changed. Instead of running away, he impetuously approached the outcast and embraced himsome say he kissed him. A new spiritual hunger had been growing in this wealthy cloth merchants son, and on the country road that day, he found himself confronted with a challenge more personally trying than battle: to love the leper as the gospel commanded.

The encounter filled Francis with a deep and surprising joy, and it helped set a new course for his life. During his soul-searching, Francesco discovered in the countryside the ruins of a church, where he began going to pray. One day while in prayer, he heard a voice speak to him from the crucifix asking him to repair the church, which Francis took quite literally. He gave the priest a large sum of money to ensure that the candle on the altar in front would never go out. Without his fathers permission, he also sold numerous bolts of fabric to raise the money for the restoration. When his father found out, he was so outraged that Francis, who had essentially stolen the goods, was forced to go into hiding.

A month later, the do-good thief came out of hiding to repent and return the money in a public hearing overseen by the bishopbut with a twist. Instead of simply handing back the money, Francesco also took off his clothes and shoes and handed them to his father too. No longer was Pietro Bernardone his father; now, Francis proclaimed, God alone was his father. Leaving his family and the townspeople speechless, Francis walked away naked and singing. Begging for bread and stones, Francis devoted himself to caring for the lepers and rebuilding the church. He also preached in the streetssometimes in songand appropriately called himself Gods Fool (in French,

![Saint Francis de Sales [Sales - The Saint Francis de Sales Collection [15 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/266802/thumbs/saint-francis-de-sales-sales-the-saint-francis.jpg)

![Saint Francis de Sales - The Saint Francis de Sales Collection [15 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/161144/thumbs/saint-francis-de-sales-the-saint-francis-de-sales.jpg)

A Gathering of Larks Letters to Saint Francis from a Modern-Day Pilgrim ABIGAIL CARROLL WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 www.eerdmans.com 2017 Abigail Carroll All rights reserved Published 2017 22 21 20 19 18 171 2 3 4 5 6 7 ISBN 978-0-8028-7445-0 eISBN 978-1-4674-4683-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Dedication For my fellow modern-day pilgrims

A Gathering of Larks Letters to Saint Francis from a Modern-Day Pilgrim ABIGAIL CARROLL WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 www.eerdmans.com 2017 Abigail Carroll All rights reserved Published 2017 22 21 20 19 18 171 2 3 4 5 6 7 ISBN 978-0-8028-7445-0 eISBN 978-1-4674-4683-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Dedication For my fellow modern-day pilgrims Contents A letter bridges distance.

Contents A letter bridges distance.