If you want to be loved, journalism is a poor career choice.

Bob Simon, CBS News correspondent

D aybreak was hours away on a humid morning in July 2018 when Trevor Kidd and I climbed into his pickup truck and headed out in search of a ghost.

We were unlikely travelling companions. I was a former newspaper reporter learning the craft of television production, and Kidd was a burly former professional athlete who had played more than a dozen years as a goalie in the National Hockey League. He hadnt played in the NHL in 14 years, and in retirement he had tried his hand in sports media as a Winnipeg Jets game analyst on TSN radio and TV broadcasts. When he wasnt following the Jets, Kidd retreated to his trailer in Kenora, Ontario, with his wife, Tiffany, and their daughters, Taylor, Kennedy and Emerson, boating and barbecuing in the summer and ice fishing and snowmobiling in the winter.

Kidd and I had spoken for the first time on the phone a few weeks earlier. He said his friends had told him that the former NHL player Joe Murphy was wandering Kenoras streets during the daytime before retreating to the bush after dusk to sleep on the forest floor.

Kidd was skeptical. He had met Murphy in January 2014 during an alumni game organized by former Edmonton Oilers star Glenn Anderson in Fort McMurray, Alberta. He remembered Murphy as eccentric, based on the brief time they had spent together, but he still wondered whether his friends were mistaken. How could a former first-overall NHL draft pick be living on the streets?

Kidd was nervous. He told me he wasnt sure what he would say to Murphy if we found him.

Im just gonna approach him and just start with hello and introduce myself. Ill just start with that, really nothing more than that. See how he is doing. I think Ill get a feel forwhether it be appearance, body languagehow hes doing and just start there. To me, theres a brotherhood here. Youve played in the league...

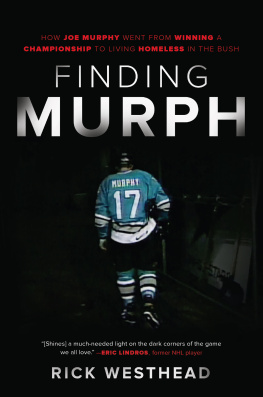

I remembered parts of Murphys hockey story. He had been a speedster who led Michigan State to a US collegiate national championship before the Detroit Red Wings selected him with the No. 1 pick in the 1986 NHL entry draft. I remembered Murphy playing for more than a decade in the NHL.

Yet, while other players maintained at least a modest public profile in retirement, signing autographs at card shows and appearing at alumni events, Murphy had disappeared since playing in his final NHL game in 2001.

During the quiet, anxious drive from Winnipeg to Kenora, as we passed forests and streams and pointy outcroppings of rock, Kidd and I struggled to process what we had been told.

What happened to Murphy?

Its possible that I was more prepared than Kidd to accept at face value what his friends had told him. I had spent years documenting the struggles of former NHL players. I had heard from the exhausted, grief-addled families of players who were coming to terms with the prospect that their sons and husbands might have a horrible disease with no known cure.

In 2016, I interviewed Mike Peluso and Dan LaCouture, former players who said their lives were in ruins. Both of them told me they had repeatedly suffered concussions while playing in the NHL and had been cleared by team doctors to return to the ice while they were still suffering symptoms of those injuries.

A one-time fighter whose NHL teams included the New Jersey Devils, Peluso couldnt recall my name five minutes after we met. He told me that he didnt call for help anymore after suffering seizures because he couldnt afford the cost of an ambulance. He shared that he had contemplated suicide many times and had once filled a candy bowl with prescription medication, but changed his mind at the last moment when he realized no one would be left to care for his dog, Coors.

LaCouture, a gritty New Englander who played for the Boston Bruins and New York Rangers, was going through a divorce from his wife, Bridey, when I met him. The couple had two children. LaCouture didnt understand why he would so often fly into an uncontrollable rage and become moody, depressed and forgetful. Bridey said her husband had changed since they had first met. He was a different person.

LaCouture told me about his fight at Madison Square Garden on January 5, 2004, against Calgary Flames defenceman Robyn Regehr. LaCouture fell backwards after he was hit by Regehr and was knocked unconscious when his head slammed into the ice. In the hours after his injury, LaCouture said he was not taken for a precautionary CAT scan, nor for an MRI. He said he wasnt even sent to a neurologist for an exam.

The Rangers stitched LaCouture up and sent him home with some painkillers. He told me hed had 17 or 18 concussions while playing in the NHL and he wondered how much the quality of care he received following those injuries had to do with his current problems.

Months before Kidd and I met, I had also reported the story of Matt Johnson, a former enforcer with the Minnesota Wild who was homeless in Santa Monica, California.

Johnsons family explained that Matt had become addicted to painkillers after being prescribed so many by NHL team doctors. They were bewildered and grief-stricken, and while they wanted Johnson to come home, they were also afraid of what he might do if he did make his way back to the family farm in Ontarios Niagara region.

Johnsons father, Lee, shared that when his son had lived at home a few years earlier, he would creep into his parents bedroom and stare at them as they slept. Lee and his wife, Brenda, were so unsettled by the behaviour that they installed a lock on their bedroom door.

Was Murphys story a similar one, or had other factors led to his decline?

In November 2013, a group of former NHL players joined a lawsuit that was filed in US District Court in Minneapolis. The players, Joe Murphy included, alleged that the NHL had not done enough to safeguard the long-term health of players who suffered brain trauma during games and had ignored medical research about the long-term implications of repeated blows to the head.

The litigation set off a venomous years-long legal battle that tarnished the NHLs image and its relationship with its former stars. Players wrote first-person accounts of their health problems in major newspapers. They wrote about suffering from memory loss, confusion, dramatic mood swings, poor judgment, anxiety and depression. The NHL argued in court filings that players didnt have the mental capacity to write their own stories and were being manipulated by greedy attorneys. The league alleged that players waited too long to file their claims and that, thanks to the publicly available information about concussions, players should have put two and two together about the consequences of repeated brain trauma.

Some former players worried that their behavioural changes might indicate they were suffering from neurological disorders such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a brain-withering disease linked to repeated head trauma that was first diagnosed in 2005 by Dr. Bennet Omalu, a forensic pathologist who worked in the Allegheny County coroners office in Pittsburgh. CTE can only be diagnosed posthumously. The diseases calling card is a distinct tangle of brain protein called tau that collects in the brains dense forest of folds and swirls.

The NHL had a major crisis on its hands.

Former players Derek Boogaard, Bob Probert, Wade Belak, Zarley Zalapski, Todd Ewen, Jeff Parker and Steve Montador all died young after showing symptoms of CTE. One-time NHL players Larry Zeidel, Reggie Fleming and Rick Martinwho were 86, 73 and 59, respectively, when they diedwere also posthumously diagnosed with CTE.