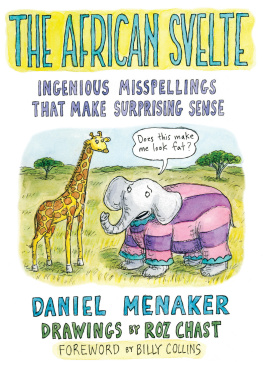

Copyright 2016 by Daniel Menaker

Illustrations 2016 by Roz Chast

Foreword 2016 by Billy Collins

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-544-80063-2

Cover illustration Roz Chast

e ISBN 978-0-544-80016-8

v1.0916

FOR KATHERINE,

with gratitude, admiration, and love

There is such a thing as the poetry of a mistake.

CHARLES BAXTER

Foreword, March!

THE FIRST TIME I was aware of Dan Menakers devotion to the fine points of language was in one of our early conversations, when he credited his mother (as he does in this very book) for his fascination with correctness and even more so with incorrectness. An esteemed magazine editor herself, Mary Grace was intolerant of improper usage to the point where she would cringe at any reference to Tiffanys. The name of the store, she would remind the offender, was Tiffany. No possessive. My reaction to Menakers anecdote was a mixture of respect and amusement at such exactitude, colored by my shame at having said and probably written Tiffanys for decades. Like other unaware people, I suspect, I was misled by Truman Capotes memorably titled Breakfast at Tiffanys, an example of a phenomenon where a more popular usage replaces the proper, and in this case I mean proper, name. Its just the kind of fine point of usage that must have inspired Dan to compile this collection of verbal clashes.

The type of misusage that preoccupies The African Svelte is the erroneous, unconscious confusion caused by some of the many homophones, eggcorns, and malapropisms that complicate our language: waiver/waver, gall/Gaul, derrire/dairy air/Derry air. You get the picture. All of us, its safe to say, have come across such mistakes in everyday life, handwritten signs in store windows being a rich source. I think what makes these errors interesting is our reaction to them. Its one thing to notice a wrong choice among their, there, and theyre, and quite another to be stopped in ones reading or tracks by a reference to the windshield factor for windchill factor.

Because such slips require a little double take on our part, they usually have a humorous effect on us, maybe for the same reason we laugh at jokes. In his book on the effect of jokes on the unconscious, Freud claims that we laugh at jokes because we perceive an incongruity, a moment of illogic that then createsyou guessed itanxiety. Our laughter, for Freud, is an effort to cover our unease. Maybe if Freud had included some funny jokes instead of the German groaners he offers as examples, he wouldnt force us to approach the mechanics of humor with such deadly seriousness.

Leavening the sense of inaptness in some of these odd couples is a remarkable and, of course, unintended kinship. To say of a relationship that one person controlled the other like a puppy on a string is wrong, but by an odd logic we recognize that in order to walk a puppy, a string might be more fitting than a leash. Many of Menakers pairings seem chosen for this kind of bonus.

A less Freudian reading of why we react the way we do to the kinds of errors that this book is all about would point out the disparity between hearing words and seeing them on the page, between listening and reading. Mistakes like to pass mustard and dead wringers are surely committed by people whose experience of English is more auditory than literary. Its the gap between those two spheres that we fall into when confronted with an error as brilliant as a pillow of strength. We are dealing with errors in translation not from one language to another but from the ear to the eye.

Words can trip us up in many ways. Deconstruction theory claims that we are always hopelessly and pointlessly tangled in the means of our own expression. Here, Dan Menaker, with a sharp ear, a keen eye, and a healthy penchant for elaboration, has isolated a particular source of verbal confusion. His catalog of slip-ups, complete with whimsical, freewheeling commentary, will appeal to anyone with a sense of humor, a taste for the absurd, and an affection for the authors favorite language.

BILLY COLLINS

Introduction: From There to Here

Or: The Journey to the African Svelte

THIS HAPPENED MORE than sixty-five years ago, in the Tens at the Little Red Schoolhouse in Greenwich Village. Our teacher, Mabel, asked if anyone knew the names of the three ships in which Columbus and his men sailed to America. We were sitting around in a circle, just talking, which is what we did most of the time. (The school must have hoped it was grooming the Marxist dialecticians of the next generation.) A little girl raised her hand and said, The Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe.

I went home and told my parents about this exchange. My mother encouraged me to write a letter about what happened and send it to The New Yorker. Under the title Westward Ho, my letter about the incident became an anonymous Talk of the Town piece:

A fourth-grade young lady at The Little Red Schoolhouse was quick with her answer the other day when she was asked to name the ships of Columbuss fleet, we are advised. Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe, she said confidently.

I was (sort of) published in The New Yorker at the age of ten! The magazine sent me fifty dollars, and the next day I went to school and gave twenty-five of them to the little girl. She was, after all, the means of production.

In the ensuing half century, writing, editing, copy editing, verbal irony (that addiction), and listening closely to conversationmy own and othershave taught me that words sometimes speak louder than actions, that they often break more bones than sticks and stones, and that all language is radically metaphoricalrepresentational of reality. All except the most rudimentary language, like mmm and wow. The word macaroni isnt macaroni. That is, the word is, obviously, nothing less than but also nothing more than a written or spoken symbol of the pasta. So you could say, and I am in fact saying, that words by their very nature are themselves metaphorsour linguistic carryings-over from the mute world.

My attention to words in turn largely degenerated, for too long, into a sense of superiority about speech and writing. Reading the slush pile at The New Yorker became a source not only of amusement but of hauteur. Mainly out of this kind of snootery, I began to keep a list of funny mistakes I came across while slogging through the pages of the fiction stories, as the hopeful submitters sometimes called them. The zebras were grazing on the African svelte was the one that started me on this list, because it was itself, in a way, so... so svelte.

Thus the title of this book. What is, at least figuratively, svelter than the African veldt? What is smoother, from a distancemore understated, more lissome? Despite my discreditable condescension, on a more decent level, I recognized the correctness, the rightness, of this mistake.

Eventually, various kinds of professional and personal humblings began to dissolve my arrogance. Meanwhile, the better specimens of slush-pile mistakes, which I had begun to think of categorically as sveltes, kept coming across my desk, at the very earliest stage of their development into what I now view as a collection of beauty and poetry. All of them had that same kind of rightness about them that in many cases equaled and in some cases superseded their wrongnesses.

That is, the funniest of these errors were funny not only because they were errorsthe verbal equivalent of trying to put a shoe on the wrong footbut because even as wrong shoes for the wrong feet, they somehow fit anyway. If you think about them, they give you the same kind of smile you get when you realize you can use the curved handle of a cabinet drawer as a bottle opener, or a nail clipper as a wire cutter, or a cars headlights as outdoor spotlights. Its the comprehension, often unconscious, that every thought our minds produce is connected to every other. Its a species of delight.

Next page