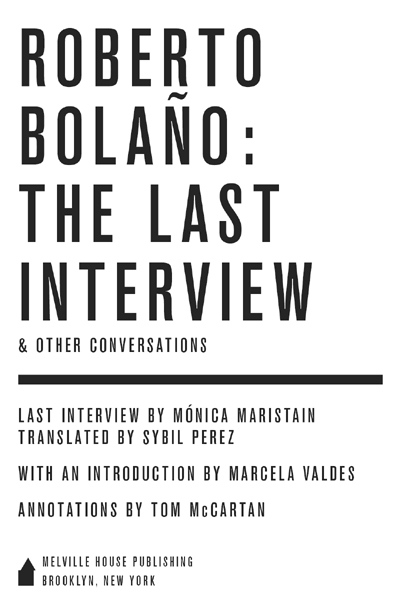

Compilation and translation Melville House Publishing, 2009

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.mhpbooks.com

eISBN: 978-1-61219-033-4

Alone Among the Ghosts Marcela Valdes. First published in The Nation, December 8, 2008. Research was supported by a grant from The Investigative Fund of The Nation Institute.

Literature is Not Made From Words Alone, by Hctor Soto and Matas Bravo, originally appeared in Capital, Santiago, December 1999, and is reprinted here by permission of Capital.

Reading is Always More Important Than Writing Bomb Magazine, New Art Publications, and its contributors. First appeared in Bomb Magazine, Issue #78, Winter 2002, pp. 49-53. All rights reserved. The Bomb Archive can be viewed at www.bombsite.com.

Positions are Positions and Sex is Sex first appeared in Revista Cultural TURIA, n 75 (ISSN: 0213-4373, 2005, pages 254-265) as Roberto Bolao: Todo escritor que escribe en espaol debera tener influencia cervantina, by Eliseo Alvarez, reprinted here by permission of Revista Cultural TURIA,

The Last Interview Mnica Maristain. First published by Playboy Mexico, July 2003, and first published in English by Stop Smiling, Issue 38, pp. 50-59. Reprinted here by permission of the interviewer.

Cover photo by Basso Cannarsa

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009939057

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Alone Among the Ghosts

Marcela Valdes

I. Literature is Not Made From Words Alone

Interview by Hctor Soto and Matas Bravo

Capital, Santiago, December 1999

II. Reading is Always More Important Than Writing

Interview by Carmen Boullosa,

translated by Margaret Carson

Bomb, Brooklyn, Winter 2002

III. Positions are Positions and Sex is Sex

Interview by Eliseo lvarez

Turia, Barcelona, June 2005

IV. The Last Interview

Interview by Mnica Maristain

Playboy, Mexico edition, July 2003

INTRODUCTION

ALONE AMONG THE GHOSTS

MARCELA VALDES

THE PART ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shortly before he died of liver failure in July 2003, Roberto Bolao remarked that he would have preferred to be a detective rather than a writer. Bolao was fifty years old at the time, and by then he was widely considered to be the most important Latin American novelist since Gabriel Garca Mrquez. But when Mnica Maristain interviewed him for the Mexican edition of Playboy, Bolao was unequivocal. I would have liked to be a homicide detective, much more than a writer, he told the magazine. Of that Im absolutely sure. A string of homicides. Someone who could go back alone, at night, to the scene of the crime, and not be afraid of ghosts.

Detective stories, and provocative remarks, were always passions of Bolaoshe once declared James Ellroy among the best living writers in Englishbut his interest in gumshoe tales went beyond matters of plot and style. In their essence, detective stories are investigations into the motives and mechanics of violence, and Bolaowho moved to Mexico the year of the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre and said he was briefly imprisoned during the 1973 military coup in his native Chilewas also obsessed with such matters. The great subject of his oeuvre is the relationship between art and infamy, craft and crime, the writer and the totalitarian state.

In fact, all of Bolaos mature novels scrutinize how writers react to repressive regimes. Distant Star (1996) grapples with Chiles history of death squads and desaparecidos by conjuring up a poet turned serial killer. The Savage Detectives (1998) exalts a gang of young poets who joust against state-funded writers during the years of Mexicos dirty wars. Amulet (1999) revolves around a middle-aged poet who survives the governments 1968 invasion of the Autonomous University of Mexico by hiding in a bathroom. By Night in Chile (2000) depicts a literary salon where writers party in the same house in which dissidents are tortured. And Bolaos final, posthumous novel, 2666, is also spun from ghastly news: the murder, since 1993, of more than 430 women and girls in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, particularly in Ciudad Jurez.

Often these victims disappear while on their way to school or returning home from work or while theyre out dancing with friends. Days or months later, their bodies turn uptossed in a ditch, the middle of the desert or a city dump. Most are strangled; some are knifed or burned or shot. One-third show signs of rape. Some show signs of torture. The oldest known victims are in their thirties; the youngest are elementary-school age. Since 2002 these murders have been the subject of a Hollywood film (Bordertown, starring Jennifer Lopez), several nonfiction books, a number of documentaries and a flood of demonstrations in Mexico and abroad. According to Amnesty International, over half of the so-called femicides have not resulted in a conviction.

Bolao was fascinated by these cold cases long before the murders became a cause clbre. In 1995 he sent a letter from Spain to his old friend in Mexico City, the visual artist Carla Rippey (who is portrayed as the beautiful Catalina OHara in The Savage Detectives), mentioning that for years hed been working on a novel called The Woes of the True Policeman. Though he had other manuscripts on submission to publishers, this book, Bolao wrote, is MY NOVEL. Set in northern Mexico, in a town called Santa Teresa, it revolved around a literature professor who had a fourteen-year-old daughter. The manuscript had already topped eight hundred thousand pages, he boasted; it was a demented tangle that surely no one will understand.

Surely, it seemed so then. Bolao was forty-three when he sent this missive, and as near to failure as hed ever been. Though hed published two books of poetry, co-written a novel and spent five years entering short story contests all over Spain, he was so broke that he couldnt afford a telephone line, and his work was almost entirely unknown. Three years earlier, he and his wife had separated; around the same time he was diagnosed with the liver disease that would kill him eight years later. Though Bolao won many of the short story contests he entered, his novels were routinely rejected by publishers. Yet late in 1995 he would begin an astonishing rise.

The turning point was a meeting with Jorge Herralde, the founder and director of the publishing house Editorial Anagrama. Though Herralde couldnt buy Nazi Literature in the Americasit was snapped up by Seix Barralhe invited Bolao to visit him in Barcelona. There Bolao told him about his cash problems and the desperation he felt over the many rejections hed received. I told him that Id love to read his other manuscripts, and shortly afterward he brought me Distant Star (later I found out that it had also been rejected by other publishing houses, including Seix Barral), the editor recalls in an essay. Herralde, however, found the book extraordinary. Thereafter, he published all of Bolaos fiction: nine books in seven years.